A peace movement took hold in Los Angeles during the most deadly and destructive rebellion in American history. The uprising was a reaction to systematic injustice rather than a direct response to police violence. The acquittal of four police officers for the March 1991 beating of twenty-five-year-old Black motorcyclist Rodney King—a two-minute assault captured on video and watched by millions of Americans on the nightly news—set off a rebellion that lasted for five days, involved the deployment of 10,072 National Guardsmen and 2,000 federal troops, and caused an unprecedented $1 billion (just under $2 billion today) in property damage. Over fifty people died, surpassing Detroit’s grim record of forty-three. Yet in the Watts section of the city, where in 1965 stores had burned, helicopters had hovered, and police and National Guardsmen had killed dozens of Black residents, in 1992 warring Crip and Blood gangs understood the rebellion not as a moment of wanton destruction, but as an opportunity to transform themselves and their community. By moving to end the violence, the gangs hoped to win political influence and to control scarce resources on their own terms.

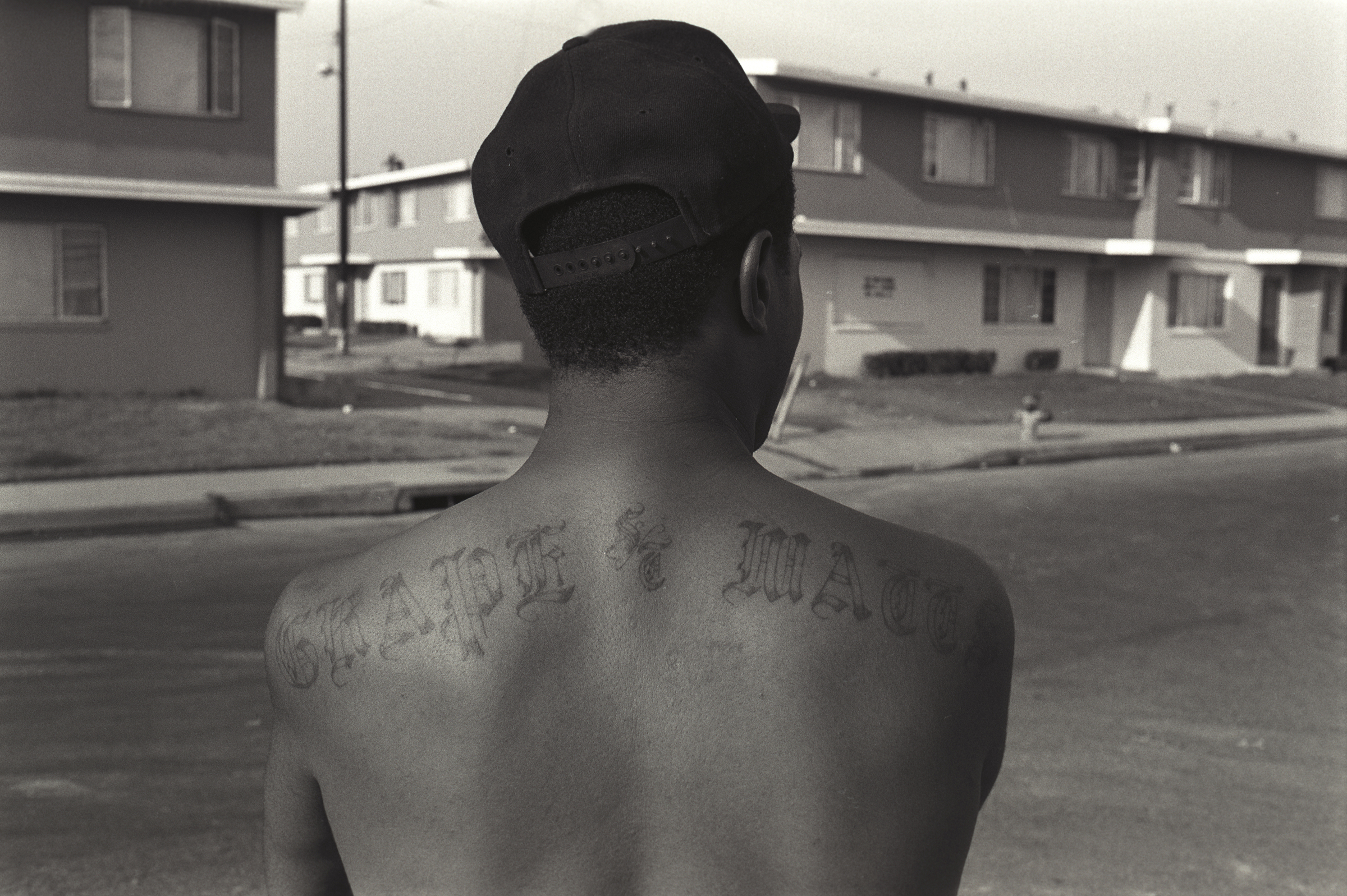

The Bounty Hunter Bloods, Grape Street Crips, Hacienda Village Pirus Bloods, and the PJ Watts Crips had intermittently discussed a ceasefire in the years leading up to the rebellion. But it took a series of discreet meetings supported by the Amer-I-Can program before any of the Crips and Bloods involved were prepared to make meaningful steps toward peace. Run by the former NFL star Jim Brown, Amer-I-Can offered “urban life management skills” classes based on the principles of responsibility and self-determination. Most of the young men in their twenties who would organize the truce in 1992 had participated in the program and had often met in Brown’s living room.

The Crips and Bloods in Watts had been at war with each other and with police in Southern California for three decades. In Los Angeles and other major cities, collective violence in the 1960s and early 1970s was directed against external state forces—most often the police, who represented the frontline of government authority in segregated urban communities. After the rebellions of that era were repressed by an increase in uniformed presence on the streets and by mass incarceration, an internal form of collective violence surfaced. With few opportunities for formal employment, even within the lowest levels of the service sector, young Black men began to form groups commonly referred to as gangs to claim and guard territory, protect themselves, and keep neighborhoods safe from outsiders. Gang members defaced businesses, schools, parks, churches, and public walls with graffiti. By force or theft, they acquired sneakers, leather jackets, and cash, establishing protection rackets to extort money from local businesses. And they clashed with one another, throwing Molotov Cocktails, attacking rivals with fists and switchblades, and firing cheap, “Saturday Night Special” handguns.

In the early 1970s, the Black Panthers and other radical organizations were no longer seen to pose a major threat, and law enforcement agencies at all levels started to concentrate on gangs, the new “public enemy number one.” Beginning in 1972, the County Sheriff’s Departments received federal funding to create a special “Street Gang Detail” squad to combat the groups.

As fears of “black youth gangs” grew, so did gang enforcement. And as gang enforcement expanded, so too did the gangs themselves, which needed increasing numbers of recruits in their push for self-protection amid the crackdowns, and in order to sustain their flourishing informal economy. Whereas in 1972, only eighteen known and active gangs existed in South Central, Compton, and Inglewood, by 1978 that number had more than doubled. And with the expansion of gangs has come the expansion of violence and killing. From 1980 to the present, Black men have constituted half of all America’s homicide victims, the vast majority of whom were killed by other Black men. By the time Ronald Reagan officially launched the War on Drugs in 1984, gang members carried Uzis, MAC-10 submachine guns, and semiautomatic rifles to enforce contracts in the underground economy. The most tragic consequence of this arsenal was the prevalence of drive-by shootings, which frequently resulted in the deaths of innocent bystanders and hastened an increasingly aggressive police response. In 1992, the reported number of gang-related homicides in LA County peaked at 803, representing a 77 percent increase over the 1988 figure. Between 1987 and 1992, the state of California expanded its spending on policing and incarceration by 70 percent. By conservative estimates, a quarter of Black youth in South Central had been arrested at some point in the years leading up to the rebellion.

By the spring of 1992, it seemed that nearly two decades of gang control measures had failed. As with the rebellions of the late 1960s and early 1970s, more enforcement seemed to only precipitate more violence in response. But the consequences for low-income Black communities were now more dire. These communities, in LA and other cities, were under attack, caught in a war among rival gangs and between gangs and the police.

Rising crime and mistrust within communities themselves—exacerbated by federal policies—are factors that generally made rebellion less frequent in the last decades of the twentieth century and into the 2010s. As President Ronald Reagan oversaw the “War on Drugs” in the 1980s, he simultaneously supported the removal of half a million families from welfare rolls, one million Americans from food stamps, and 2.6 million previously eligible children from school lunch programs. At the same time, violent crime increased alongside the zero-tolerance policing of the drug war and mandatory minimum sentencing provisions; together, these factors rendered mass incarceration a foregone conclusion. The higher probability of getting harmed or shot led parents in vulnerable areas to call their children home after school. The higher likelihood of getting robbed led grandparents to install additional dead bolts and chains on their doors. The prospect of retaliation led people to be careful about the clothing they wore and kept victims from talking openly with police (whom they probably didn’t trust anyway).

People learned to comply with officers during routine encounters—to keep both hands on the steering wheel, to answer questions politely—in order to stay alive. They armed themselves in case they had to shoot their neighbor. Yet as the 1992 rebellion raged and the city burned, members of the Crips and the Bloods in Watts set out to bring the internal warfare to an end, and to face a common external enemy—systemic racism, embodied most immediately by the police—as a united front.

Formal truce talks started three days before the rebellion broke out. On April 26, 1992, a dozen Grape Street Crips, led by two Amer-I-Can participants, twenty-five-year-old Daude Sherrills and his twenty-three-year-old brother Aqeela, drove the two miles south from the Jordan Downs housing project to Imperial Courts, where their PJ Crips rivals lived. The two groups made a peace pact and partied together afterward, marking the end of two decades of violence and fear.

Los Angeles blew up the next day, Wednesday April 29, 1992. Roughly ten minutes after it was announced that the four officers who brutalized Rodney King had walked free, crowds gathered at the Pay-Less Liquor and Deli on Florence Avenue in South Central. The police started making arrests, prompting more people to join in to protest the police. Some went to LAPD Headquarters, smashing windows and chanting “No Justice, No Peace.” Others looted stores at the intersection of Florence and Normandie or attacked motorists. Most of the victims of the random attacks were Latin American or Korean, but a news helicopter captured the beating of white truck driver Reginald Denny by a group of Black men, and this incident—presented as the counterpart to the Rodney King video—became the iconic image of the rebellion.

When the sun went down, the mass looting and arson began. Across Los Angeles County, from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach, stores were ransacked and burned, ultimately causing damage to more than one thousand buildings and leaving more than two thousand people injured—both participants and bystanders. Although non-Black-owned businesses were hit in South Los Angeles, much of the violence targeted the immigrant communities of Koreatown and Pico-Union. Tensions between Black and Korean residents had increased since mid-March the year before, when, two weeks after Rodney King’s assault, Black ninth-grader Latasha Harlins was fatally shot by a Korean storeowner over a $1.79 bottle of orange juice. Harlins’s killer, Soon Ja Du, received probation, community service, and a five hundred dollar fine after facing charges of voluntary manslaughter. In April 1992, the Rodney King verdict was the national story, but Harlins was on the participants’ minds. “Rodney King? Shit, my homies be beat like dogs by the police every day,” a member of the Bloods explained. “This riot is about all the homeboys murdered by the police, about the little sister killed by the Koreans, about twenty-seven years of oppression,” he said, invoking the 1965 Watts rebellion as an origin point. Rodney King was “just the trigger.”

In stark contrast to most prior rebellions around America, the collective violence in Los Angeles was multiracial and multiethnic. Just over half of those arrested were of Central and South American descent; overall, this demographic made up roughly 40 percent of the city’s total population, and many within it linked the Rodney King case to the police brutality they faced, too. In August 1991, five months after the King video circulated around the world, LAPD officers and sheriff’s deputies gunned down two young Latino teenagers in separate incidents, sparking a wave of protests in East LA. “Fuck the police! They diss us just as much as the blacks,” a Salvadoran teenager announced to reporters outside two looted stores in Koreatown during the 1992 rebellion. While many Latin American participants spoke of a shared struggle when they took to the streets, the media mostly depicted them as “illegal aliens” who exploited Black protest for their own personal gain, conjuring a racist stereotype that obscured the scale of police violence in Black and Brown communities and, by extension, their legitimate political grievances.

Read More: 40 Ways to Build a More Equitable America

On Friday, May 1, the third night of unrest, President George H. W. Bush addressed the nation, just as Lyndon Johnson had during the Detroit rebellion in 1967. Bush referred to the King beating as “revolting” and said that he and Barbara Bush were “stunned” by the verdict. Many white Americans shared the first couple’s reaction to the sight of officers pummeling King some fifty times with weighted batons and shooting him with their Tasers. This was the first viral video of police brutality, exposing white Americans to state violence in Black Los Angeles and Black America. Bush was not prepared to offer a critique of police brutality or the justice system, but he admitted “it was hard to understand how the verdict could possibly square with the video.”

Professing to be disturbed by the King verdict, Bush also assured the American people he would use “whatever force is necessary to restore order.” His administration sent two thousand riot-trained federal officers to Los Angeles and placed the three thousand National Guard troops already stationed there under federal command. Attorney General William Barr invoked the Insurrection Act to quickly organize the federal force, which consisted of FBI and Border Patrol agents, special SWAT teams, US Marshals, and prison riot squads, in addition to thousands of Marines and Army soldiers, all of whom were stationed in the city for ten days. In total, more than twenty thousand law enforcement officers and soldiers cooperated to arrest an incredible 16,291 people and put down the rebellion.

The possibility that the “riot” in Los Angeles was a political act did not factor into Bush’s analysis. “What we saw last night and the night before in Los Angeles, is not about civil rights,” the president told the nation. “It’s not about the great cause of equality that all Americans must uphold. It’s not a message of protest. It’s been the brutality of a mob, pure and simple.” The Bush administration explicitly linked the “mob” to gang violence. In the 1960s and 1970s, authorities had blamed communists, “outside agitators,” and militants for the destruction. Now Barr and other authorities held gangs and undocumented immigrants responsible, viewing the violence as a problem endemic to those groups.

Federal, state, and local officials also saw the chaos as an opportunity to advance repressive campaigns against the “gangs” and “illegal aliens.” “A number of aliens have come into this area and are involved in crime,” Chief of Police Daryl Gates claimed in an interview. “They were participating in this riot in a very, very significant way.” During the rebellion, police officers would stop possible gang members or undocumented migrants without cause other than to assess their status. Those found to be gang members were added to police and FBI databases, while those determined to be “illegal” were prosecuted by Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) and the Border Patrol, which had dispatched four hundred agents to Los Angeles. Arrest and deportation became yet another tactic government authorities used to manage the violence resulting from unequal socioeconomic conditions and racial oppression. And as in every prior rebellion, a harsh response led more people to rebel. It was, in a sense, the antithesis of the plan the Crips and the Bloods in Watts proposed for South Central.

When the rebellion started at Florence and Normandie, graffiti in Watts already announced the truce agreed to the day before. The uprising had the effect of cementing it. Unity parties in Imperial Courts and Nickerson Gardens went on as the surrounding areas burned. On May 3, the day before the rebellion ended, the Pirus Bloods in the Hacienda Village housing project entered the accord, meaning that there would be peace throughout Watts going forward. Even during the rebellion, the truce made a difference. Compared to South and East LA, property damage in the area was light. Shootings continued among gangs in other neighborhoods, but police alone were responsible for the three deaths in Watts.

There had been prior attempts to negotiate a cease-fire, but the 1992 truce succeeded because it was the first initiated by Crips and Bloods themselves. In 1972, the year “black youth gangs” started making headlines in the Los Angeles Times, the city’s Commission on Human Relations sponsored a day-long seminar at the LA Convention Center for gang members from South Central and the segregated Black city of Compton. The boys and young men believed that “black people should have more control over their own community,” and agreed to “come together in unity” to organize a broader truce if they were provided with jobs, better schools, and better recreational facilities. These investments never materialized, and so the young people did not hold up their end of the bargain, either.

The official response to the “gang problem” was draconian. New anti-gang policing measures revolved around surveillance, violence, and incarceration.

Under the leadership of Darryl Gates, who served as the LAPD chief of police from 1978 until he was forced out after the 1992 rebellion, the department prosecuted a vigorous war on drugs and gangs that was deeply racist in its premise and methods. In a May 1982 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Gates famously remarked on the use of choke holds by police: “We may be finding that in some blacks when it is applied, the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as they do in normal people.” Amid the police war on “abnormal” people of color, between 1980 and 1990 the number of misconduct charges nearly doubled, as did the number of reported gang killings.

Beginning in the spring of 1987, more than a thousand LAPD officers would sporadically swoop into South Central to carry out mass arrests as part of a recurring campaign called “Operation Hammer.” The purpose of the program, as Gates explained, was to “make life miserable for gang members.” Over the decade’s remaining years, more than fifty thousand people, most of them Black, were interrogated and detained for parking fines, traffic citations, curfew violations, outstanding warrants, and “gang-related behaviors.” Officers exhibited “gang-related behaviors” themselves. In one particularly violent raid on two apartment buildings—during which police ransacked homes, tore up family photos, smashed toilets, and poured bleach on residents’ clothes—officers tagged the community with their own graffiti.

Operation Hammer created or extended criminal records for significant numbers of Los Angeles residents. Only ten percent of the people arrested during the sweeps ended up facing criminal charges, but police classified the majority of those they arrested as gang members and entered them into the computerized database which eventually had over one hundred thousand names. At the time of the 1992 rebellion, 47 percent of Black men and teenagers in Los Angeles were classified by law enforcement authorities as gang members. Names appeared in the database multiple times, leading to a distortion of the gang problem.

But in the summer of 1988, as residents and gang members understood, the mass violence and arson had the effect of fostering a sense of solidarity and unity among previously warring neighborhoods. “We are coming together because we are Black,” said a twenty-three-year-old who identified himself simply as “Anthony.” “We are tired of being divided.” The truce meant members would no longer have to live under the constant fear of getting shot, or with the belief that it was necessary to shoot someone themselves. The rebellion was a moment when internal violence was set aside in favor of fighting an external threat. Even when the violence stopped, the focus on the police and the larger system remained.

As the truce came into effect, organizers planned programs in the Watts community to promote it. Over the weekend of May 16 and 17, as Governor Pete Wilson withdrew the remaining three thousand National Guardsmen from Los Angeles, the Crips and Bloods sponsored a Saturday “unity picnic” and a Sunday family event, inviting the entire community “to come out for a peaceful day of food and recreation.” More than five thousand people showed up, men and women from both sides of the war as well as people who were not involved in it except as bystanders. People played football and danced together. Congresswoman Maxine Waters made an appearance, applauding the peace agreement and vowing to create more jobs in South LA and Watts.

Organizers went beyond parties, picnics, and speeches, in the knowledge that the problems went deeper than violence. The larger goal was to restore Watts, with the support of local organizations including the Coalition Against Police Abuse (CAPA) and Community Youth Gang Services. “We will clean up our community from graffiti and trash and prove to media, police and everyone else that we are not outcast just out to do wrong,” a flyer promoting one of the new initiatives proclaimed.

Those who struck the truce understood that its success depended on whether the drug and black-market opportunities that lured people into gangs could be replaced with jobs in the formal economy. “The gangbangers that are in the community, that are slinging drugs—put an economic plan together and then they’ll quit selling drugs,” said PJ Crip Tony Bogard, a key figure in the peace negotiations. “You have to substitute something.” Reconstruction would have been necessary, in the minds of those pushing for it, even if the city was not undergoing the largest rebellion in American history. Bogard and other organizers took the rebellion as an opportunity to push the city for a massive investment in health care, education, and employment, and they called for residents themselves to have a say in how it was apportioned.

Local authorities had other ideas in mind. On May 2, the day President Bush declared Los Angeles a disaster area, Mayor Bradley announced the formation of Rebuild LA, entrusting the fifty-four-year-old businessman Peter Ueberroth, a resident of Orange County, with directing the program.

In mid-May 1992, as Ueberroth vetted candidates for the Rebuild LA board, members of the Crips and the Bloods drafted a comprehensive proposal for a $3.728 billion investment into the community that would accompany the end of the internal warfare. The ten-page document became known for its memorable closing line, “Give us the hammer and the nails, we will rebuild the city.” The majority of the funds, or about two billion dollars, would be spent on “LA’s Face Lift”: building new community centers and recreation facilities to replace burned and abandoned structures, erecting more street lights (“we want a well-lit neighborhood”), properly maintaining the landscape (“new trees will be planted to increase the beauty of our neighborhoods”), and improving trash removal and pest control. The proposal also called for universal health care and the construction of new hospitals, health care centers, and dental clinics; for an end to welfare through new jobs for able-bodied workers; and for free daycare for single parents.

There was another request, too: $700 million for the complete transformation of the Los Angeles Unified School District. The funds would be used for the renovation of derelict public schools, including remodeling and repainting deteriorating buildings and upgrading bathrooms to make them “more modern.” Students would have access to computers, supplies, and up-to-date textbooks—and enough copies so the books would no longer need to be shared. Another portion of the money would take the form of federally funded bonds for high-performing students to help them attend college.

The Crips and Bloods also no longer wished to be policed by a gang of outsiders. “The Los Angeles Communities are demanding that they are policed and patrolled by individuals who live in the community and the commanding officers be ten-year residents of the community in which they serve,” their proposal explained, putting forward residency requirements as a straightforward step to improve police-community relations. To promote community oversight of policing, former gang members would have a role in “assisting the protection of the neighborhoods” through what the drafters conceived as a “buddy system”: former gang members would accompany officers during every encounter, in what would have essentially represented the institutionalization of the Black Panthers’ Community Alert Patrol from the 1960s and 1970s. The community members involved in the program would undergo police training and “comply with all of the laws instituted by our established authorities”; they would be issued uniforms but not guns. Instead, “[e]ach buddy patrol will be supplied with a video camera and will tape each event and the officers handling the police matter.” The idea was that if an officer was knowingly filmed, he or she would be less likely to engage in brutality or lawlessness—the premise behind the police body cameras that would become relatively common across the country in the twenty-first century.

The drafters of the proposal recognized that change needed to come from both the community and the authorities. In order to build a vibrant formal economy in place of the existing, underground economy in communities with high rates of unemployment and underemployment, the proposal urged federal and state authorities to make loans available to “minority entrepreneurs interested in doing business in these deprived areas”—in other words, to give illicit organizations an opportunity to establish legitimate businesses. Entrepreneurs who received these loans would be required to hire 90 percent of their workforces from within the community. “In return for these demands,” the proposal promised, “the Blood/Crips Organization will request the drug lords of Los Angeles . . . to stop drug traffic and get them to use the money constructively.” The drafters of the proposal gave authorities seventy-two hours to commit their support in writing, thirty days to begin implementation, and four years to construct three new hospitals and forty health care clinics, as well as to renovate the schools.

The final, complete treaty included a code of ethics authored by Daude Sherrills, one of the leaders who forged the truce. “I accept the duty to honor, uphold and defend the spirit of the red, blue and purple,” Sherrills’s preamble read, referring to the colors of the Watts gangs, “to teach the black family its legacy and protracted struggle for freedom and justice.” Aligning the truce with the civil rights and Black Power movements, the code encouraged gang members to register to vote and to pool their investments to sponsor cultural events, establish a food bank, and provide hardship funds to families in need. It prohibited the use of the “N-word and B-word” as well as “hoo-riding,” or throwing up gang signs.

Well before it was formalized, the truce had a measurable impact in reducing violence that went beyond the five days of rebellion, when onetime rivals had had more reason to unite. For years, Black male gunshot victims had filled the emergency room at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital near Nickerson Gardens and Imperial Courts on weekends, but in the first weekend after the rebellion and the truce, doctors did not operate on a single Black male with gunshot wounds. “Usually there’s an onslaught” of Black victims, said Kelvin Spears, an emergency room physician at the hospital. In May and June, only four people were killed, down from twenty-two during the same period in 1991. Drive-by shootings fell by nearly 50 percent from 1991 to 1992, and gang-related homicides by 62 percent.

Almost overnight, Watts enjoyed a new kind of simple, straightforward freedom, with residents now trusting each other more. Children could play in their front yards without their parents worrying that they would be caught in the crossfire. “Now it’s quiet, peaceful,” said Watts resident Kecia Simmons. “You can take a walk, water your grass. You don’t have to worry about anything.” People no longer felt constrained in choosing which colors to wear or which neighborhoods to visit. As one resident put it, the truce gave those in Watts “a better chance to live like people.

Most in the community saw law enforcement as the biggest challenge to the endurance of the truce. “I don’t have to worry about the gangs,” said a former gang member named Duke at a press conference. “I have to worry about the police.” The LAPD had maintained their existing tactics, despite the drop-off in violence. The police had even seen the parties celebrating the truce as an opportunity to arrest large groups of people, in some cases in the hopes of causing a violent reaction.

Yet the Crips and Bloods who had signed on to the peace agreement remained committed to unity. “More police are patrolling because they cannot believe that Bloods and Crips are hangin’ together,” a twenty-six-year-old named Kenneth, who had been a gang member since his teenage years, assumed. “They say things to try to push us, but we know that they are trying to divide us and make us do something that will cause bloodshed. We ain’t even sweatin’ them though. Our whole thing is to get organized and to love one another.”

The truce movement—with young people working together to clean up the community and increase public safety while demanding jobs and justice from the authorities—was puzzling to law enforcement, who viewed the decline in violence in Watts and South LA with cynicism. “Time will tell whether or not we are dealing with a real situation where they definitely want to return to society,” said Detective Bob Jackson, one of the LAPD’s “gang experts.” Sergeant Wes McBride admitted to a reporter that, “To be quite honest with you, we just don’t know why black gangs are not killing each other.”

The LAPD claimed to have intelligence from informants that the truce movement promoted violence against the police. Even though officers allowed that just as many informants told them otherwise, they embraced the “war on police” narrative. In LA in 1992, the police needed to keep the gang war alive. If there was peace in the community, and no need for the war on gangs that had shaped policing strategies in Los Angeles for nearly a decade, what would police do?

In the face of testimony from residents about how the truce had improved their lives, LAPD officials insisted that Black people in South Central and Watts still lived in fear and they moved to increase police patrols. “It’s not as if the truce means that the gang members have found God or suddenly seen the light,” South Bureau Homicide Detective Jerry Johnson argued. “They are just as violent, but they have shifted their activities away from each other and toward the community,” Johnson asserted, pointing out that drug deals, robberies, and other street crimes had not entirely vanished. The LAPD deployed a large “crime suppression task force” to aggressively patrol gang neighborhoods

Although the “Bloods/Crips Proposal” did not make an impression on the authorities, its drafters established business ventures of their own in the months after the rebellion. As the LAPD was reinforcing its crime suppression task force, leading organizers partnered with the sneaker company Eurostar, headquartered in South Los Angeles, to develop a line of shoes promoting the truce. The shoes, to be manufactured in Korea, would feature either the red, black, and green colors of the Black Liberation Flag or the red and blue of the Bloods and the Crips, respectively, with a label reading “TRUCE” on the heels. The various sneaker designs were given names such as “The Motivator,” “The Educator,” and “The Facilitator.” The sneaker enterprise offered Crip and Blood factions hope that the truce would translate to real economic gains, and was initially heralded by city officials as a model job program for former gang members. Rebuild LA Director Peter Ueberroth praised the shoe line as an example of “doing it right”; President Bush even sent a letter to the founders applauding their efforts.

Eurostar, which reported $57.4 million in sales in 1991, invested $600,000 in the sneaker line. The money was supposed to go toward paying rent and training employees, with the idea that the former gang members would eventually assume control themselves.

But empowerment, at least in the commercial sphere, would have to wait. The market-based approach to recovery that won the praise of the president and the local business community came to little, in the end. Eurostar never delivered on its promise to put the sneaker line into mass production, and the business faltered by the summer of 1993. With “the cameras gone” and the free advertising gone with them, Eurostar’s enthusiasm faded.

Rebuild LA met with a similar fate. Ueberroth and other officials showed little interest in partnering with Crips, Bloods, and other community representatives, despite making rhetorical gestures to grassroots empowerment. So, it was little surprise that Rebuild LA failed to deliver on the promise of jobs and relief for businesses damaged during the rebellion. It invested less than $400 million in the revitalization effort, falling far short of its lofty goals and the sums—in the $4–$6 billion range—that would have been required to set South Los Angeles on a meaningful road not just to recovery, but to transformation. Ueberroth resigned from Rebuild LA after only one year, following an internal evaluation that found the organization was little more than “a convenient excuse for inaction.” By 1997, it had disbanded.

Despite the broken promises of the business community and politicians, the truce between the Crips and Bloods in Watts not only held but spread. Violence continued to decline in the communities that embraced the new politics of unity. In the year after the rebellion, homicides throughout Los Angeles County dropped by 10 percent, the first decrease since 1984. In Jordan Downs, Nickerson Gardens, and Imperial Courts, gang-related deaths declined from twenty-five in 1987 to four in 1997, with the treaty still in effect by the latter date.

It would not last much longer. That year, one of the original organizers of the armistice said, “I think this community is more hopeless now that it was before,” even if violence never returned to the disastrous earlier levels. “They have no hope that anything is gonna change. They see nothing has been done within that five years.” A veteran gang probation officer named Jim Galipeau offered a similar assessment: “The only tragedy of the truce was that society needed to reward” the gang members who created it, yet “didn’t do a damn thing.”

Given the continued lack of jobs, substandard housing, limited educational opportunities, and police harassment—all of the conditions that precipitated the rebellion in the first place—the old status quo seemed destined to reemerge. Crime, collective mistrust, and exhaustive policing ultimately prevailed. That the armistice in Watts held for a decade was remarkable.

Like the 1960s and 1970s rebellions, the massive, nationally televised rebellions from 1980 onward were carried out by people who wanted not only an end to police violence, but a chance to rebuild their communities and live their lives on their own terms. Yet policymakers consistently resisted socioeconomic solutions, focusing instead on increasing the scale of crime control resources and ultimately supporting the expansion of the prison system to contain troublesome groups. While many Americans understand the period from the 1960s to the 1990s and into the present as one of transformation and even of progress on many fronts—including the diversification of numerous workplaces, increased political representation for people of color, and general prosperity—the rebellions across these decades indicate that for many low-income communities of color, there was more continuity than anything else.

This essay is adapted from Elizabeth Hinton’s new book, America on Fire: The Untold Story of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s. Published by Liveright.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com