Three weeks after Bethany Fauteux gave birth to her second child in 2013, she was spending her days surrounded by young children—except they weren’t her own. A single mother whose cash reserves were quickly depleting, she felt she had to return to her job as a preschool teacher in Massachusetts while her Caesarean-section scar was still throbbing.

She recalls lying to her obstetrician about her pain level in order to be cleared to return to work. “I faked it to seem like I was fine, like this didn’t affect me at all,” she says, “and it felt like my insides were ripping out.”

If Fauteux, now 37, had lived in a country like Hungary or Italy or Spain or Romania at the time, she wouldn’t have had to return to work so soon to keep earning a paycheck. But while individual companies in the United States grant 17% of civilian workers paid family leave, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and at least nine states have enacted laws providing the benefit, the U.S. remains the only industrialized nation in the world that doesn’t have a national paid family leave law on the books. The U.S. also lags behind other countries on childcare affordability, with the cost of center-based daycare averaging roughly $10,000 per toddler, per year. (These stressors were exasperated during the pandemic, as millions of parents—usually mothers—had to step back from work to care for their kids as schools shuttered and other childcare options remained cost-prohibitive.)

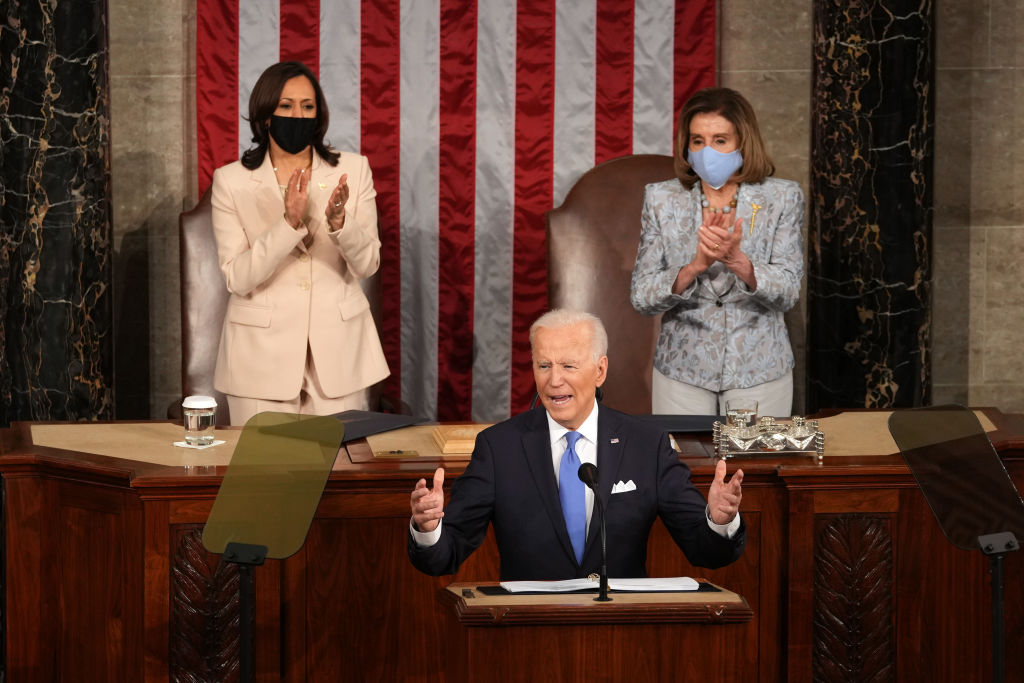

With an expansive $1.8 trillion proposal called the American Families Plan that he unveiled on April 28, President Joe Biden is attempting to change that. The plan, which follows his $2.2 trillion American Jobs Plan, would provide three- and four-year-olds with free, universal pre-K; create a national paid family and medical leave program that eventually provides 12 weeks of up to 80% wage replacement to families who are caring for a new child or sick relative, healing from an illness, or grieving the death of a loved one; offer all students two years of free community college; extend tax cuts geared toward low- and middle-income families; and invest in a sliding-scale system that ensures most families don’t pays more than 7% of their income on childcare for kids under 5. The White House estimates that the child care plan alone would save families roughly $15,000 per year in expenses.

The key word, however, is would. Biden cannot sign a bill that contains these proposals into law unless the House and the evenly divided Senate pass them first—and thorny procedural questions about how to pass the bill are causing rifts even among Democrats. So far, Republicans have signaled no openness to supporting Biden’s ambitious ideas. “100% of my focus is on stopping this new Administration,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said last week. “We’re confronted with severe challenges from a new Administration, and a narrow majority of Democrats in the House and a 50-50 Senate to turn America into a socialist country, and that’s 100% of my focus.”

The central issue isn’t just money. The debates also focus on what investments should count as “infrastructure” and how to prioritize them. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, for instance, argues that both the American Jobs Plan—which would invest trillions into physical structures like roads, bridges, pipes, airports and internet broadband—and pieces of the American Families Plan should fit into the same category. “We build roads and bridges so people can get to work and we invest in broadband communication so people can get to work,” the Massachusetts Democrat tells TIME in a statement. “It is time to treat childcare just like any other forms of infrastructure because investments in child care also get people to work.”

But some Republicans on the Hill argue sweeping trillions of dollars of spending under one category is disingenuous. “We have what is infrastructure, and we have what’s not infrastructure,” a GOP aide says. “Now, the issue is that we’re talking about infrastructure, but [Democrats] have a bunch of policies that are hidden into a massive spending bill… You’re basically turning it into a Trojan Horse at that point.”

Turning discussions and debates into actual bill text will likely take weeks or months, multiple aides predict, but taking too long could hurt the plan’s prospects. “Our best shot of getting it done and keeping it popular is moving fast,” a Democratic aide says. As lawmakers wrangle over the American Families Plan, financial decisions for many American parents hang in the balance, as does nearly $2 trillion in government spending—another colossal price tag in Biden’s progressive bet on big government.

‘We need to get these proposals passed’

Democrats are already threatening to jam the American Families Plan through without any Republican support. “I believe that we need to get these proposals passed, and I do think that it’s important to do outreach to Republicans,” says Rep. Judy Chu, a California Democrat. “But I do not want to waste time by negotiating with people who may not have any investment in getting those items passed.”

To pass the bill the traditional way, Democrats in the Senate would need to get at least 10 Republicans on board. But a Senate Democratic aide says the party doesn’t feel optimistic about that prospect. A recent Morning Consult poll indicated 58% of Americans support the American Families Plan, yet the aide points out that despite 75% of voters supporting the American Rescue Plan, according to a Politico/Morning Consult poll, not a single Republican in either chamber of Congress voted for the bill which provided most Americans with a third round of stimulus checks in mid-March. If zero Republicans supported popular legislation to combat an economic crisis in the midst of a public health crisis, the Democratic aide argues, then it’s unlikely they will support these more expansive proposals.

That’s why Democrats like Chu support passing the plan through reconciliation—a special legislative mechanism that enables certain tax, spending and debt-limit legislation to be passed in the Senate by a simple majority vote. But not every member of her party agrees. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat and arguably the most powerful member of the Senate, is weary of using the process of reconciliation to advance sweeping legislation. “For the sake of our country,” he said in late April, “we have to show we can work in a bipartisan way.”

‘Working families don’t care how it happens’

Manchin’s caution alone could sink the White House proposal—especially if the Families Plan ends up being a standalone bill.

Anticipating gridlock, some Democrats are weighing the merits of combining the $1.8 trillion American Families Plan with the $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan into one massive piece of legislation. If split, the Jobs Plan would be based on more physical components of infrastructure—like funding for roads and bridges—and the Families package would focus on rebuilding America’s middle class through measures such as free community college, creating a safe and affordable childcare system, unveiling universal pre-K and phasing in paid family leave.

Some Democrats argue that keeping the proposals separate doesn’t make sense, because the components of each plan are intertwined. Making two years of community college free, says a Senate Democratic aide, would prepare individuals to take on skilled trade jobs in the construction and infrastructure realm that the Jobs Plan creates. Similarly, making childcare more affordable would enable more parents to go out in their communities and get these new jobs.

Manchin, on the other hand, has indicated he wants to prioritize traditional infrastructure like roads and bridges, and called the $568 billion Republican counter-offer to Biden’s $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan a “good start.” That GOP plan outlaid $0 for what some academics call the “Care Economy”—which the American Families Plan aims to address.

If Democrats accede to Manchin and try to pass the Families Plan after passing traditional infrastructure policies first, the Families Plan might not make it through, another Democratic aide suggests. “If they put all the easy stuff in the first package, what is going to happen to the second package?” the aide says.

Dawn Huckelbridge, the director of Paid Leave for All and Paid Leave for All Action, argues that most Americans don’t mind whether passing these care policies requires reconciliation or lumping everything into one large bill. “Working families don’t care how it happens,” she says. “They care that it passes.”

Bethany Fauteux, now a line cook, agrees. She doesn’t care what legislative maneuvers it takes—so long as she never has to choose between her income and caring for her family. At the beginning of the pandemic, she was again faced with this impossible catch-22 when her mother collapsed while babysitting her kids. Her mom needed long-term care, but Fauteux couldn’t take any paid time off to be with her. “It felt so impossible because I still had to work and make money,” she says. “I felt like I was failing everybody.”

-With reporting from Lissandra Villa from Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com