Like many Jews on Christmas Eve, Jordan Frazes was bored. She didn’t have the option to meet up with friends or hit up a Chinese restaurant; the pandemic kept her sequestered at home in Chicago with her parents. So when she got a notification about a “Matzo Ball” room on the audio app Clubhouse, she tapped in to join. “It became this hysterical thing where you’re talking to strangers, but it feels really comfortable,” she says; she stuck around for six or seven hours. Since then, Frazes and a growing cohort of Jews—from around the world and from all denominations—have built an unusually focused and education-oriented community on the app, where thousands of listeners and speakers tune in regularly for events like weekly Shabbat, hours-long talks from Holocaust survivors and even a celebrity-studded Passover Seder with guests like Jeff Garlin and Ari Melber.

Frazes considers herself culturally Jewish but not particularly observant. Still, she is aware of the crisis of anti-Semitism spiking around the world: anti-Semitic attacks reached a near all-time high in 2020 according to the Anti-Defamation League, which tracked over 2,000 incidents of anti-Semitism in the U.S. alone. Experts link the rise to a lack of education about Judaism and Jewish history. A 2020 survey showed a troubling decline in Gen Z and Millennial knowledge about the facts of the Holocaust; as many as 63% of U.S. respondents did not know that six million Jews were killed, and 11% believed Jews caused the Holocaust.

Lack of regulation on social media fuels such misinformation, and Clubhouse has been no exception. The tech industry’s latest buzzy social media platform, which launched last fall, now claims over 10 million users on its iOS-only app, and has been valued at $4 billion as of mid-April. The app was an early hit for tech, business and music celebrities, with appearances from Elon Musk, Paris Hilton and will.i.am. It has also been the focus of concerns about anti-Semitic, misogynistic or other problematic speech, which has festered in some corners of the app. Despite this, a fervent Jewish community has grown on the platform, with a mission to spread cultural knowledge.

Since that fated Christmas Eve experience, Frazes, who runs a consulting and PR agency called Frazes Creative, has become something of a super-user, even organizing a weekly post-Shabbat event called Havdalah. “We wonder how long this community will stay together, and we ask the question sometimes to the room,” Frazes says. “The response is: please, please continue this, we love this. And my response is that if we’re making that difference in ten people’s lives, or 30 people’s lives, or 50, it makes a difference to me.”

The experience of using Clubhouse is akin to walking into a giant, maze-like university building: there are cavernous lecture halls filled with thousands of people in attendance and just a couple of speakers at the stage, and there are small round-table discussion sections that feel like cozy hangouts among friends. You don’t really know what you’ll find until you open the door and peer in. Sometimes you’ll get a chance to speak; sometimes you won’t. As its initial surge of new user acquisition slows—in March, new user growth dropped 72% from its February high—some prognosticators are already bearish on its future. Competition is everywhere: Twitter recently launched Twitter Spaces; Reddit is preparing to kick off Reddit Talk; Facebook has plans to roll out live social audio rooms.

But not all have already constructed a vibrant Jewish world of their own. Adam Swig, the executive director of non-profit organization Value Culture, has been one of the most prominent organizers moderating inclusive Jewish-oriented spaces on Clubhouse; he and his Value Culture “room” were behind that first Matzo Ball experience. Prior to the pandemic, Swig organized events in his native San Francisco like Shabbat at the Symphony and “Goat My Valentine,” a Valentine’s Day party featuring—you guessed it—goats. He learned quickly over the past year how to attract audiences to digital events; his Zoom Shabbats, like one focused on Black and Jewish solidarity, and one partnered with a special needs non-profit, counted thousands of attendees. But Clubhouse has proved more fruitful. “I was reaching thousands of people globally instead of hundreds of people locally,” he says. Swig started spending as many as 40 hours a week on the app.

Much of that time has been devoted to special events featuring Holocaust survivors. That younger generations are under-informed about a critically important historical event is a global concern; even German politicians are wary of this trend, especially as the far right gains ground in legislatures around Europe. Swig, alongside rapper Kosha Dillz, brought 81-year-old Holocaust survivor and speaker Sami Steigmann to the app to share his experiences in late January for International Holocaust Remembrance Day. It ended up being a 16-hour marathon of a room—continuous conversation across time zones, with over a thousand audience members of all nationalities, ages and backgrounds tuning in to ask questions. Swig and Value Culture have since hosted more salons with survivors. “Never before [have we had] the access to this global audience, together, on these topics,” Swig says. For listeners, hearing from survivors firsthand can be eye-opening.

Kianta Key, a social media strategist from Georgia, stumbled upon the Holocaust talk almost by accident on a slow afternoon. “I couldn’t believe there was an octogenarian on Clubhouse or that this person, who had lived through the horror of the Holocaust, was sharing his journey with a bunch of strangers,” Key says. “I‘ve likened the experience to the late 1930s effort to collect narratives from people who had been enslaved.” The audio aspect of Clubhouse, Key says, deepens the human connection, stripping away some of the artificiality of social media, and breeding empathy.

Steigmann’s perspective on surviving trauma especially hit home with Key. “He didn’t condemn or offer anything that was on the spectrum of hateful for those who carried out these orders or for anyone else who denies his experience,” she says. “It’s inspiring especially given the state violence on Black and Brown people and the increased anti-Asian violence over the last year. How can I get the peace and grace of Mr. Steigmann?”

For Bidisa Mukherjee, a San Francisco Bay-area sales operations analyst, the Holocaust survivor talks have been a welcome history refresher. “I only remember learning about the Holocaust one year out of my four years of high school,” she says. “I think hearing from the mouth of someone who has lived through it really puts a lot of things into perspective. It doesn’t feel so far away.”

Much of the Jewish education on Clubhouse is more lighthearted than the Holocaust storytelling. Often, it’s just a chance to hang out, like at the Havdalah Room. Usually, Havdalah—the ceremony that marks the formal end of Shabbat and the start of a new week—is an experience saved for Jews who are actively observant. But on Clubhouse, all are welcome to join the chat and set some intentions.

Jonathan Emile, a Jamaican-Canadian musician living in Montreal, has become a Havdalah regular. “My wife Ruth was exploring when she stumbled across a room called ‘Shabbat Stallone or Sylvester Shalom.’ She was simply intrigued, so she joined the room where a small group of people were just having a blast cracking jokes,” he says. (It was a Shabbat after-party room, hosted by Swig’s Value Culture.) That led them to join other Havdalah rooms and attend Holocaust remembrance events. Neither Emile nor his wife are Jewish, but they have found connection in the Jewish community on Clubhouse. “It’s great to talk about allyship, but by actually listening and participating in a Havdalah or a virtual Shabbat, one can really learn,” he says. Plus, he has found meaningful parallels between his own lived experiences and those of the Jews he is getting to know online, particularly when it comes to the historical oppression of both groups. “[I’ve learned about] the constant uphill battle against racism, the longing for self-determination, being painted in caricature, and the disunity that tradition, trauma and disparate ethnicity often bring,” he says. “Often we get painted in stereotypes with prejudice strokes. Seeing the diversity of Judaism in ethnicity, race and tradition on full display through testimony, music and conversation is really—truly—powerful.” Emile wrote a song called “Moses,” and he performs it often in the Havdalah Clubhouse room, at listeners’ requests.

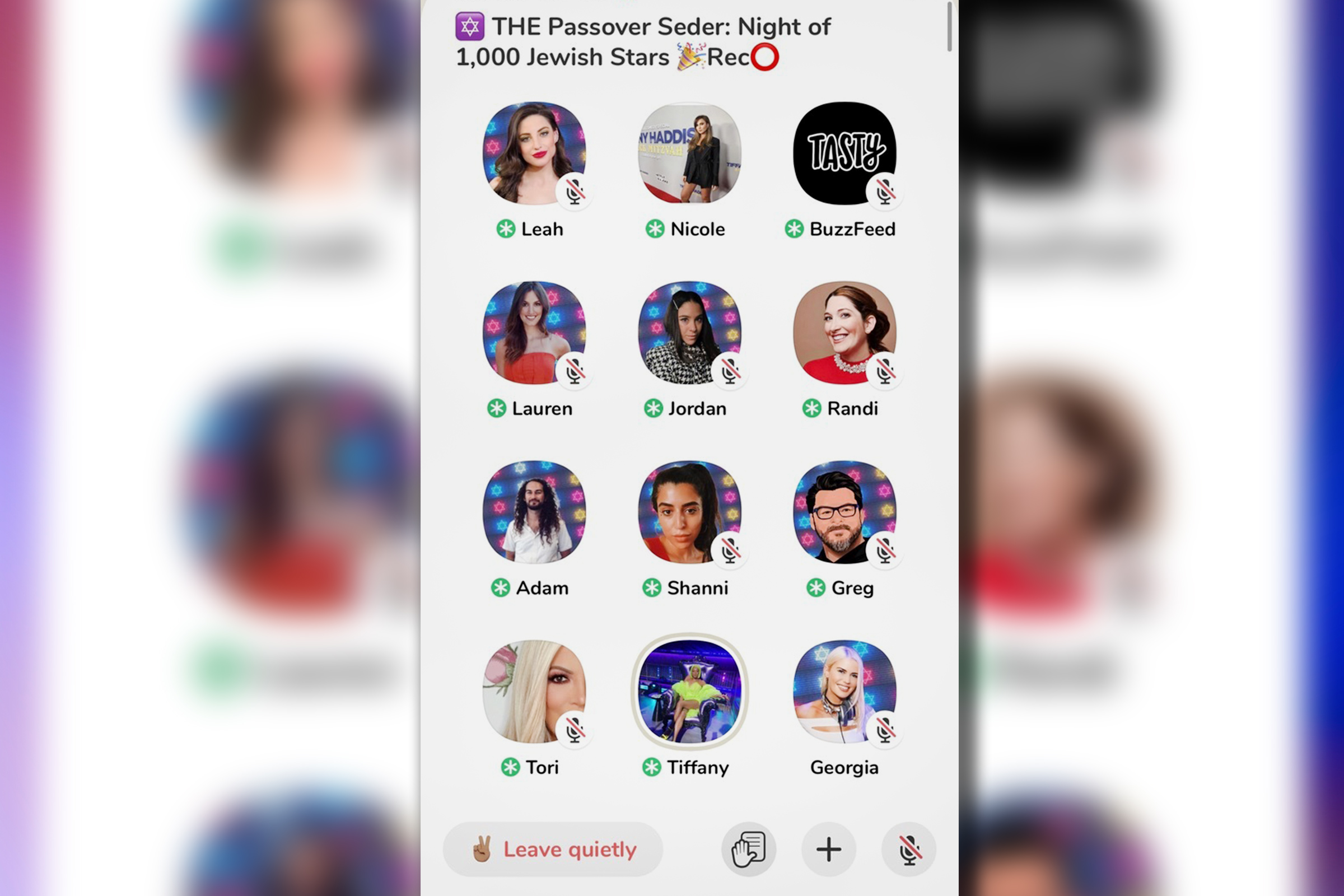

For Frazes, the diversity of the chats has helped her connect with Jewish traditions even more. Swig is focused on broadening the community’s appeal. “A Night of 1,000 Jewish Stars,” a four-hour Passover Seder Swig and Frazes helped organize featuring celebrities like Tiffany Haddish and Tori Spelling brought in 43,000 attendees. (They also welcomed techies with the sale of a matzo NFT.) Swig is proud of his efforts, and sees real progress educating young people on the app about Jewish culture. “We did it on Clubhouse, we came together during the pandemic,” he says, “and we created a future.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Raisa Bruner at raisa.bruner@time.com