Over lunch nearly 20 years ago, approaching the end of her life and feeling ready to speak of her experiences for the first time, my great-aunt Hélène Podliasky shared with me the story of her escape from the Nazis. I had known she was a member of the Resistance, a collection of multiple underground networks fighting in France against the German occupation from 1940 to the liberation in 1945. But I did not know about Hélène’s arrest and deportation to Ravensbrück, nor about her escape, with eight other women, from a Nazi labor camp. After she described how they traveled through the German landscape across the front lines of the war in search of the U.S. troops, finding the names of these women and what had happened to them would become my obsessive detective work over the next years. I feared I had waited too late; in the gap between when I recorded Helene’s story and when I set off on the trail of her escape, the last of the nine had died.

The work of uncovering their stories was filled with fortunate meetings and strange coincidence but also gaps in memory, silences and the haunting of intergenerational trauma.

Many times, when I interviewed a close friend or family member of one of the nine, I was told, “She never talked about the war.” In general, women in the Resistance kept quiet about what they had done. Weddings were called off when it was discovered a woman was a camp survivor. De Gaulle only acknowledged six women in his honorary list of 1038 compagnons de la liberation, the World War II heroes of the liberation of France. Women had played a large role in the Resistance, but, the thinking went, they should be content that at last in 1944 they were granted the right to vote. Two of the nine were Jewish, but managed to keep this hidden in Ravensbrück, where they were assigned the red triangle of political prisoners, and not the yellow that would have put them in even more danger.

After the war Hélène’s best friend in the camps, Zaza, defied that trend: Rather than keeping silent, she wrote her account of their escape—though she left out the full identities of the other women, perhaps to protect them. It would be first published 60 years later. She wrote bitterly that French prisoners of war and local Germans assumed that they were voluntary prostitutes who had seen an opportunity to “service” the SS and the “free” workers in the camps. The idea that they risked their lives transporting arms, passing messages or sheltering their comrades in the Resistance was not considered possible, much less the horrors they had been subjected to upon their arrest and deportation. Because they were young pretty girls, in their 20s, they were not taken seriously.

It would be worse for women who were made to wear the black triangle, the so-called “anti-social elements” who made up the largest population of Ravensbrück in the early days of the camp. These were women who had what was considered deviant behavior, which included homelessness, alcoholism and prostitution. Often these women were young girls who had run away from home, perhaps from violence and sexual abuse. They could be widows who found themselves homeless in bombarded cities. Some were lesbian couples who had been denounced. They were disdained by the other prisoners. Many sex workers were forced to work as sexual slaves in Nazi brothels. Then after the war, returning home, these women were publicly humiliated for having slept with German soldiers. There were no survivors’ groups for them to join, no one recognized them as a persecuted community. We know very few of their names.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

I was honored to meet some of the remaining survivors from Ravensbrück. I learned about the women who, after the war, created support groups, collected testimonials, and fought to keep Ravensbrück as a memorial site. Women such as Germaine Tillion, Jacqueline Fleury-Marié, Lise London and Genevieve De Gaulle did speak up after the war, and they fought for women’s contributions to be recognized. Tante Hélène, speaking through the generations, passed her story to my daughter Sophie who, in her early 20s, is the same age as the nine women were when they risked their lives to fight fascism. They were called terrorists, tortured, imprisoned, and later ignored, but today my daughter can celebrate them as role models of solidarity and resistance. It is not too late to tell these stories, and worth the effort it takes to undercover them.

When I met with possible sources, Sophie often traveled with me. Our first trip was an attempt to follow the escape route from Leipzig to Colditz. When we drove across France to La Rochelle to meet Zaza’s family, it happened to be the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War I. Afterward, as Sophie and I walked around the city draped in flags, we talked about how wars never really end; they reverberate through generations. Together, Sophie and I went to interview France, someone I had been searching for since the start—she was born to one of the nine, to Zinka, while she was in prison. France was only 18 days old when she was taken away from her mother. When France and I embraced we both cried. I said to her, “I have been searching for you for so long.”

“Imagine how I feel,” she said, “finding out all this about my mother after 70 years.”

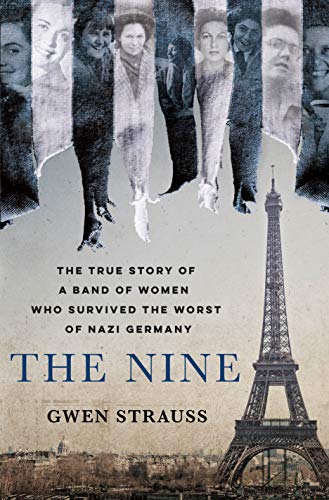

Gwen Strauss is the author of The Nine: The True Story of a Band of Women Who Survived the Worst of Nazi Germany, available now from St. Martin’s Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com