When World War II began on Sept. 1, 1939, Hannie Schaft and the sisters Truus and Freddie Oversteegen were just 18, 16 and 13 years old. But despite their youth, they formed a famous trio in the Dutch resistance: Hannie, studying to be a human-rights lawyer, was the intellectual; Truus was their decisive, down-to-earth leader; and the feminine and fierce Freddie would map out their missions.

They gathered vital information, provided Jewish children with safe houses, stole identification papers, bombed railways and, most perilously, seduced high-ranking Nazi officers, luring them into the woods and killing them.

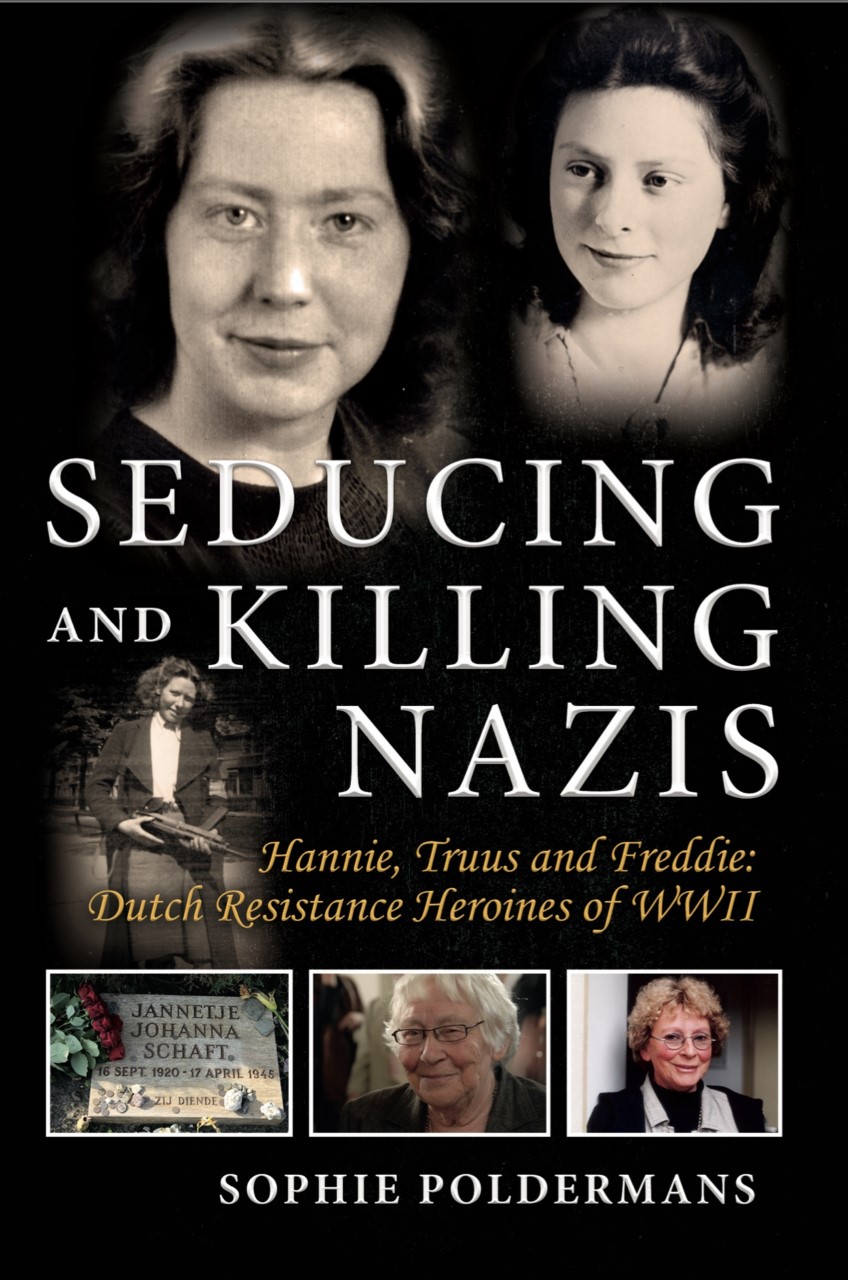

Hannie Schaft was executed by the Nazis three weeks before the end of the war. This legendary fighter known as the “girl with the red hair” became the icon of female Dutch resistance. Truus and Freddie Oversteegen survived the war, but carried emotional scars for the rest of their lives.

A half-century later, when I was about the age they had been when the war began, searching for my identity and for strong female role models, I became captivated by Hannie Schaft’s life story. A high-school research project on her life led to a chance to interview Truus Oversteegen—whose contact information I discovered through a friend of my father’s, and who was kind enough to invite a young student to her home—and to the chance to learn a lesson that went far beyond my classroom: Fighting injustice and doing the right thing takes exceptional strength and bravery, and is harder and more brutal than you might imagine, but is crucial to a livable world.

I remember my first visit with Truus like it was yesterday. She could easily have been my grandmother, feeding me cookies and asking me if I liked her new glasses. But underneath that surface lay a whole different world. The hand that shook mine when she invited me in had held a gun, a gun that she had used to kill people. Over tea, she started telling me her story and that of Hannie and her sister Freddie, emphasizing its value for future generations, like mine. Truus immediately saw how serious and dedicated I was to the cause, believed in me as a member of the new generation bearing the same ideals, and trusted me with the ability to share her story.

Truus asked me to be the keynote speaker at the annual Hannie Schaft Commemoration in 1998 and to join the board of the Netherlands’ National Hannie Schaft Foundation. There, I also got to know Freddie. A very special bond developed between the two sisters and me that lasted almost 20 years. (Truus died in 2016 and Freddie in 2018.)

I have no romantic image of their work. They were no cowgirls. They inspired me on many levels, but their work in pursuit of the right thing was, by necessity, ruthless. And getting to know the Oversteegens, I also witnessed their own struggles to come to terms with the past. They both suffered from what nowadays would probably be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), enduring severe nightmares, screaming and fighting in their sleep. Hannie Schaft’s letters, as well as testimony from her friends and fellow resisters, suggest she also suffered from depression and PTSD during the war, prior to her arrest and execution.

Given what they went through, that lingering struggle makes sense.

“While I was biking, I saw Germans picking up innocent people from the streets, putting them against a wall and shooting them. I was forced to watch, which aroused such an enormous anger in me, such a disgust, a feeling of ‘dirty bastards.’ You can have any political conviction or be totally against war, but at that moment you are just a human being confronted with something very cruel. Shooting innocent people is murder. If you experience something like this, you’ll find it justified to act against it,” Truus once told me, as I recount in my book about the trio, Seducing and Killing Nazis. “Once, I was confronted with an SS soldier, a Dutch SS soldier even, who was killing a small baby by hitting it against a wall. He grabbed the baby and hit it against the wall. The father and sister had to watch. They were obviously hysterical. The child was dead. I shot that guy. Right there and then. That wasn’t an assignment, but I don’t regret it.”

The extent of those moments remains a mystery even to me. As Freddie told me, “you shouldn’t ask a soldier how many people he shot”—and they were soldiers too.

After the war, both Oversteegen sisters fought for recognition of their resistance work. Truus expressed herself in her art, shared her story through speeches, and became famous worldwide. Freddie lived a more secluded life, focusing on her family.

However, during the last years of her life she yearned for more acknowledgment of her role. I remember a surreal discussion between the two sisters, where they were quarreling about which of them shot one particular Nazi spy. In 2014 they both finally received the Dutch Mobilization War Cross and each had a street named after them.

So many years after doing their work in the shadows, they were glad for the public recognition. They wanted their stories to be known—to teach people that, as Truus put it, even when the work is hard, “you must always remain human.”

Sophie Poldermans is the author of Seducing and Killing Nazis. Hannie, Truus and Freddie: Dutch Resistance Heroines of WWII, available now, and a Dutch women’s rights advocate, author and public speaker. She knew Truus and Freddie Oversteegen for 20 years and worked closely with them for over a decade as a board member of the National Hannie Schaft Foundation.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com