President Joe Biden’s job approval rating has hovered around a healthy 53% since he took office. Americans largely approve of his handling of the economy and the pandemic, polls show. But he’s gotten low marks in recent weeks for his response at the southwest border as an increasing number of unaccompanied children from Central America continue to arrive. Just around 29% of Americans approve of his Administration’s actions as it scrambles to house, vet and place thousands of children with family members and sponsors in the U.S.

So when Biden’s White House on Friday announced it wouldn’t immediately increase the Trump Administration’s historically low ceiling of allowing 15,000 refugees into the country, immigration reform advocates immediately saw it as a calculation to ease that political pressure by signaling the Administration is taking it slow opening the country to new migrants. In February, Biden’s White House had informed Congress it intended to raise the limit on refugee admissions to 62,500 for the rest of the government budget year ending Sept. 30. The surprise Friday announcement was seen as going back on that promise.

As it turns out, Biden’s move backfired spectacularly. He got blasted by his allies on the left and received little credit from conservative pundits for being tough on refugees. Stephen Miller, the architect of Trump’s restrictive and hardline immigration policies, agreed with immigration advocates on Biden’s motive, and called it a win for Republicans who have been on the attack over the border for weeks. He wrote on Twitter that the move reflected “Team Biden’s awareness that the border flood will cause record midterm losses *if* GOP keeps issue front & center.”

White House officials denied keeping the low refugee cap was a political calculation and told reporters that the refugee admission process had been largely dismantled by the Trump Administration and would take time to stand back up. Until then, they said, they expected to be unable to resettle as many refugees as they had thought. By the end of the day Friday, the White House reversed itself again, and promised that by May 15, Biden would likely raise the number of refugees it would admit.

It was a public relations fumble for what has been a largely disciplined White House. On Saturday, after a game of golf in Delaware, Biden told reporters that the attention and resources his administration was expending to house and place children coming alone to the border had chipped away at its ability to do other things. “Problem was, the refugee part was working on the crisis that ended up at the border with young people. We couldn’t do two things at once, so now we are going to raise the number,” Biden said, referring to the fact that some personnel at the Department of Health and Human Services that usually work on refugee resettlement had been detailed to help with the border surge.

The U.S. refugee system is run separately from the country’s border security apparatus and the way it places unaccompanied children with families. Having a large number of people coming to the border illegally shouldn’t impact how many refugees can be settled in the U.S.

But the reverse could be true, immigration advocates say. Increasing the number of refugees allowed into the country—and adding the resources to make that happen—is an important part of reducing the number of people who decide to come unlawfully to America’s borders in the long term, they say. “If you are worried that letting people in is going to be a political problem, so you set the caps low, all that is going to do is create disincentives to legal pathways to immigration,” says Jess Morales Rocketto, co-chair of Families Belong Together, a campaign to end the separation of families by immigration proceedings. “We should be doing everything we can to increase legal pathways.”

In fact, raising the number of refugees the U.S. will accept was already part of a broader playbook to open more legal avenues for migration that Biden’s team developed in the months before he took office, according to two people who worked on the transition team. If more people are offered a legal avenue to come to the U.S., more people will board a plane to get here instead of trying to walk across the border, the argument goes.

To that end, the Biden Administration is considering standing up centers in Central American countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, where people can apply for legal avenues to reach the U.S., through agricultural and non-agricultural work visas, lodge refugee claims and, if the Administration decides, grant immigration parole status to allow for family members to join other family in the U.S., as has been done for family members from Cuba and Haiti in the past. In one step to open a wider legal path, the Department of Homeland Security on Tuesday announced it was setting aside 6,000 temporary work visas, called H2-B visas, for workers from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

“If you can increase the refugee processing in Central America, you can stop people from making this journey in the first place,” says John Sandweg, who was acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) during the Obama Administration. “It’s not a magic wand. It’s not going to fix it entirely. But it is a piece of the overall puzzle when it comes to stopping the flow of people going to the southern border.”

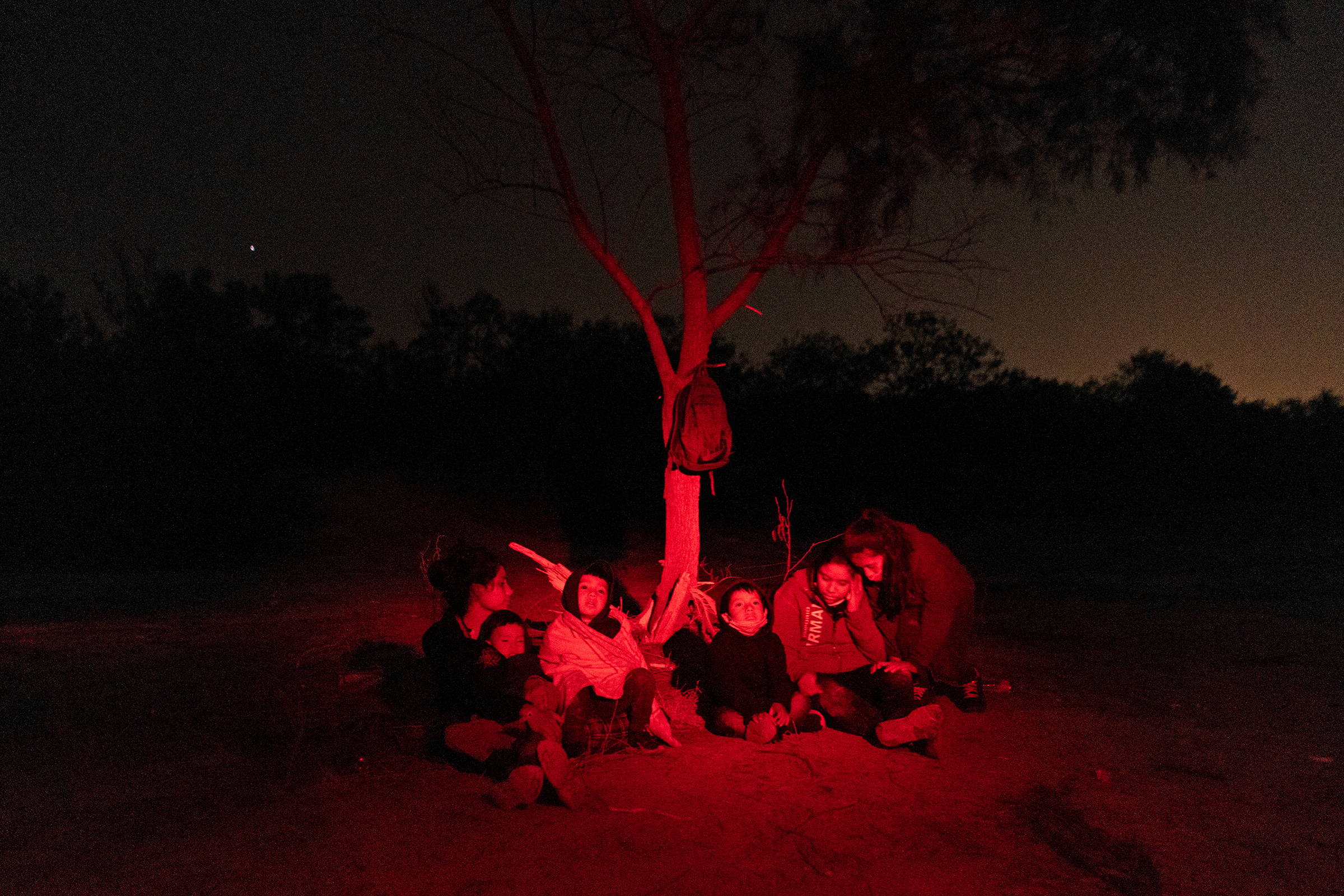

People are arriving at the U.S. border for many different reasons, and, increasingly from around the world. Some are looking for work, others want to join a parent or close relative here. Many making the journey from Central America have been displaced by storm damage from hurricanes Eta and Iota that hit blasted through Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala in November 2020, while others are fleeing gang violence or political repression.

Right now, there aren’t many ways for people to get to the U.S. aside from trying to move through Mexico illegally. Applying for refugee status in a second country is a long process, and only a sliver of the world’s refugees get permanently resettled in the U.S., even when the ceiling has been much higher. Trump reduced that cap from 85,000 in 2016 to 18,000 last year. “They were dealt a hand that was really challenging by the Trump Administration, really handed them a depleted system,” says Peter Boogaard, communications director for Fwd.us, an organization founded by Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates that advocates for immigration and criminal justice reform.

The White House has left in place Trump-era restrictions to limit travel during the pandemic, including on most visas. The Biden Administration is still turning back into Mexico the vast majority of single adults and most families caught crossing the border between ports of entries. As of now, one of the few ways to enter the U.S. for most people is to present themselves to a Border Patrol agent at the border and enter the asylum system.

“There’s only one door in place,” says Dan Restrepo, former senior director for Western Hemisphere affairs at the National Security Council under Obama. The refugee resettlement system was “systematically dismantled” while Trump was president, he says, and the Biden Administration “is starting in a worse place.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com