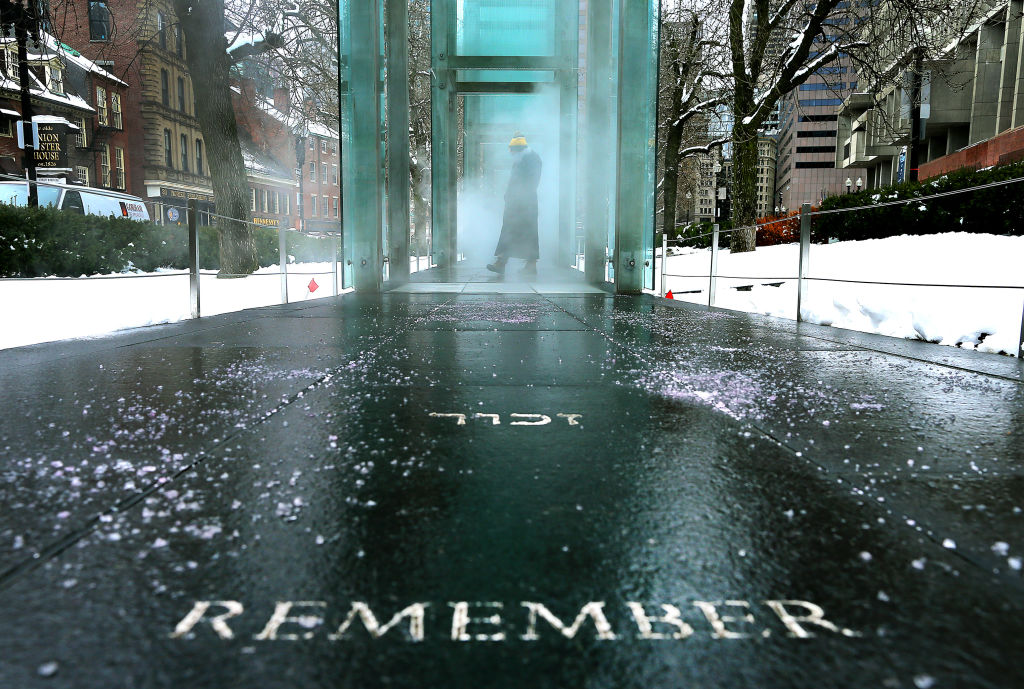

As people around the world pause this Thursday to observe the solemn occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day, it is worth asking what exactly is being remembered. In recent years, surveys released by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany with the participation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum have found some alarming gaps in public knowledge about the Holocaust. In 2018, for example, 45% of adult U.S. respondents couldn’t name a single camp or ghetto.

There is no question that the world needs better and more Holocaust education. As we think about how best to do this in the 21st century, we need to ensure that future generations learn not only what happened during the Holocaust but also how and why.

Nazism did not emerge from nowhere. The Holocaust did not begin with concentration camps, ghettos or deportations. People didn’t wake up one day and decide to participate in mass murder. In fact, the Nazis had been in power in Germany for eight long years before the systematic murder of the Jews began.

Centuries before that, religious antisemitism had flourished in Europe. Then, in the 19th century, a new racial form emerged. The influential German ethno-nationalist and journalist Wilhelm Marr argued that Jews and Germans were separate biological “races” locked in an eternal struggle with each other for survival and that “mixing” of the “races” was harmful to Germans. He advocated for the forcible removal of all Jews from the country—even those who had converted to Christianity. He did so 18 years before Hitler was even born.

Hitler would build on that deep-seated antisemitism. Exploiting Germans’ fears and resentments he offered hope and unity as well as hatred and used the power of propaganda to advance his agenda in a democratic system.

In order to win mass support, Nazi propaganda—both its positive, aspirational messages and its demonization of Jews and others—was skillfully targeted to particular audiences depending on their attitudes, which were measured in an early version of opinion polling.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

One of the common messages was designed to make Germans feel that if they were hurting economically it was the fault of the Jews. Sidney Zoltak, a survivor born in Poland, remembers when he was only 4 years old, in 1935, visiting his grandparents’ store. In an interview, Zoltak explained, “In front of their store there were young people with signs: Don’t Buy From a Jew. Don’t Buy From a Jew. I didn’t know what antisemitism was, but that was the first act of antisemitism that I witnessed. Antisemitism in Poland at that time was not only tolerated, but it was encouraged.”

The Nazi regime restricted the marketplace of ideas and used propaganda to focus on trying to convince all Germans that indeed there was a “Jewish Question” that needed to be solved.

The goal was to emphasize that your Jewish neighbors were not German, but a different race, that they did not belong to the “national community,” and had no place in Germany. The purpose of these efforts was to stoke hate if possible, but at the very least to ensure acquiescence to growing anti-Jewish measures and, eventually, removal and destruction. With the help of Nazi propaganda, Germans became increasingly indifferent to the plight of their Jewish neighbors. What ended in killing fields and gas chambers thus started long before—with ideas and words.

Holocaust survivor Aron Krell, born in Lódź, Poland, put it this way: “We heard the words… the Jews were cursed, the Jews are traitors and all of the problems in the world starts with the Jews, therefore what we have to do is get rid of the Jews.”

Hateful rhetoric built a case for Hitler’s Nazi regime to separate, isolate, dehumanize and ultimately exterminate an entire group solely for who they were. Plain and simple—it’s easy to kill those who are defined as less than human.

Survivor Irene Weiss has recalled riding the train with her father when she was 12 years old, when a group of “Nazi hoodlums” approached, easily identifying him as Jewish due to his beard. “What should they do with this Jew?” she recalled. “They said, it would be great to throw him off the train. The only reason he wasn’t thrown off the train was because they arrived at their destination.” He never rode the train again, and he was later murdered at Auschwitz.

These recollections from survivors are part of a new digital campaign launched by the Claims Conference, #ItStartedWithWords, which aims to remind the world that the Holocaust didn’t start with killing; it started with words. The campaign will post weekly videos of survivors from across the world reflecting on those moments that led up to the Holocaust—a period of time when they could not have predicted the ease with which their long-time neighbors, teachers, classmates and colleagues would turn on them, transitioning from words of hate to acts of persecution and violence, and eventually to genocide.

Without understanding the causes of the Holocaust and without thinking about how it might have been prevented, we are not honoring the victims. Nor are we serving the past—or the future.

Sara J. Bloomfield is director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Greg Schneider is executive vice president of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com