In the televised interview given by Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, and Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex, to Oprah earlier this week, the couple spoke of the way they had been treated by the Royal Family, and the racist media headlines that increasingly targeted Meghan after the couple’s wedding in 2018.

“When I joined that family, that was the last time, until we came here, that I saw my passport, my driver’s licence, my keys. All that gets turned over. I didn’t see any of that anymore,” Meghan said, speaking candidly about experiencing suicidal thoughts and wanting to seek help for her mental health, yet being told by “The Firm” that she couldn’t.

These details, of how the Firm operates, as well as the racist coverage of Meghan, struck a chord with historian Priya Atwal, author of Royals and Rebels: The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire, whose research specializes in empire, monarchy and cultural politics across Britain and South Asia. On March 7, the day before the interview aired in the U.S., Atwal posted a Twitter thread detailing the experiences of other people of color from across the British Empire who became Queen Victoria’s “godchildren” over the 1850s and 1860s, noting some of the parallels between the way they were treated by the institution and the press, and the current situation with Meghan. The thread quickly went viral, and Atwal was “blown away” by its popularity.

She says that despite the different circumstances, comparisons between the situations show how little has changed within the machinery of the monarchy. “The problem remains that the culture of royalty and the way the institution operates to protect its own image is actually very problematic. It tries to assimilate these people, because ultimately, it doesn’t care about those people to the same degree as it does about the crown,” says Atwal. “And if the interests of the crown are being messed with, then it doesn’t really matter what collateral damage happens to the lives of those people that are being assimilated. They are expendable.”

Queen Victoria’s imperial godchildren

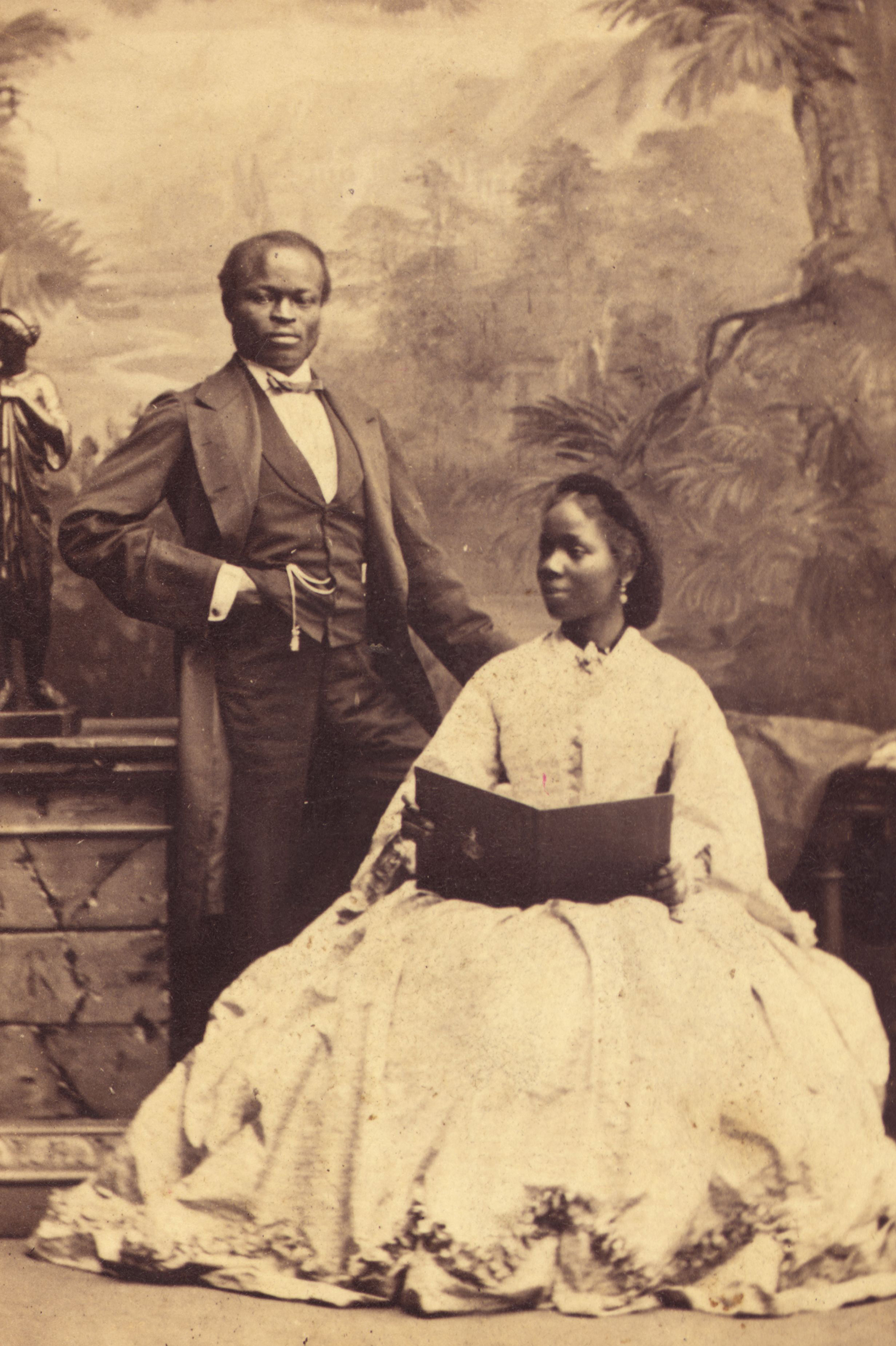

The mid-19th century was a period of rapid change for Britain, the British Empire and the British monarchy. The Empire was dramatically expanding around the world, with control of India transferring to the direct rule of the British Crown starting in 1858, and trading networks in Asia and Africa plundering nations for their natural resources. Starting with Sarah Forbes Bonetta, who was born in West Africa and held captive for two years before being presented as a “gift” in 1850 to a British naval captain representing Queen Victoria, the monarch informally adopted several wards as her godchildren from different corners of her vast empire. And while Atwal says that Victoria did take a personal interest in all of these young children from across the Empire and took them under her wing, “they essentially were put up as poster children in many respects.”

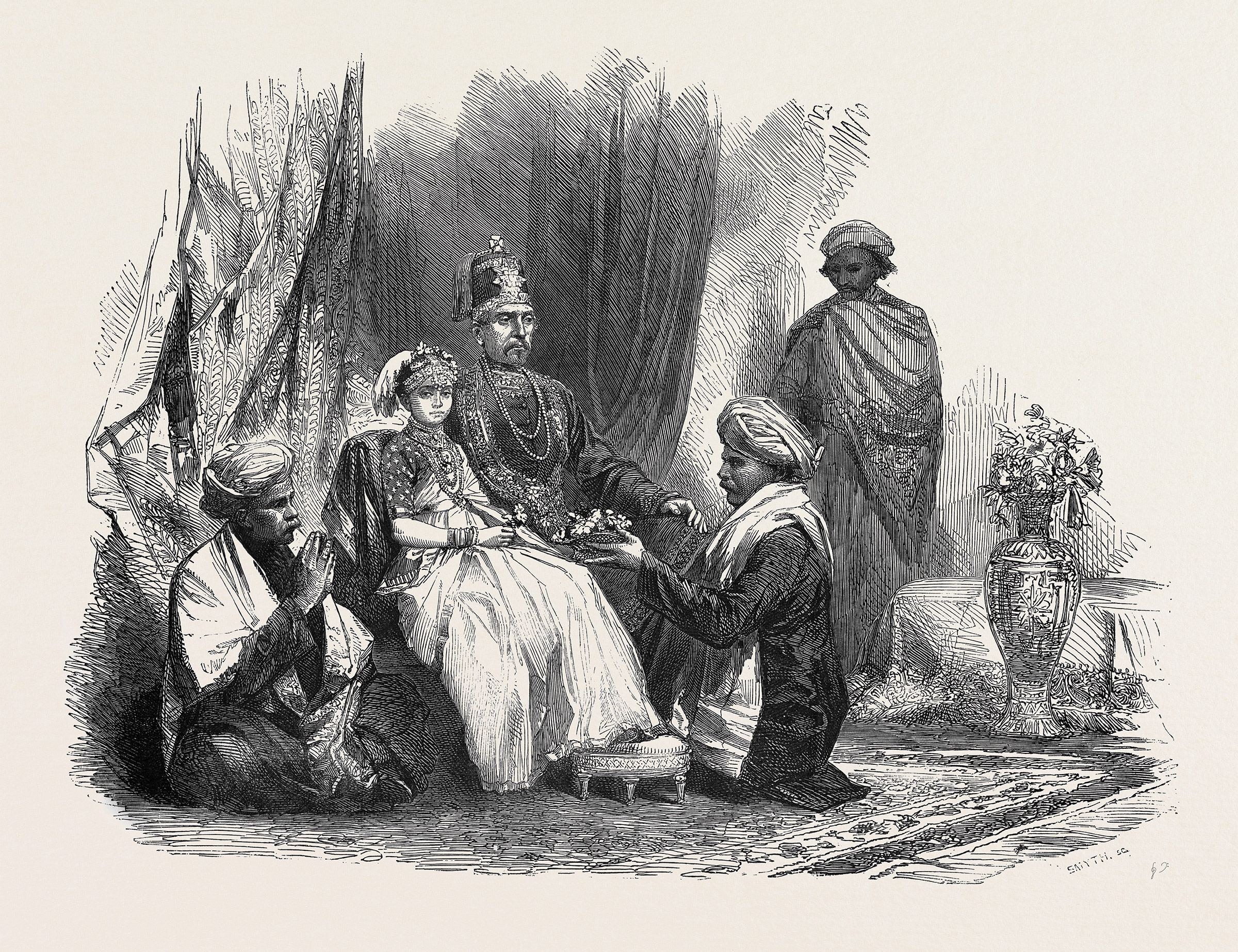

Among them were Princess Gouramma of Coorg, who came with her father to England in 1852 at the age of 11, after they were exiled and deposed from rule by the British in southwest India. Gouramma became the first Indian Royal to convert to Christianity and took on the name Victoria in her baptism, in a ceremony where the Queen became her godmother. And while Gouramma was often seen with the Royal Family and was given fine clothing and jewelry along with the title of honorary princess, her life and upbringing was closely controlled by Queen Victoria. “Victoria doesn’t allow Gouramma to see her father again, and Gouramma eventually loses the ability to speak Hindi, her mother tongue. It’s really cruel,” says Atwal. “The lens through which Gouramma is seen is through this colonial mindset. It’s all about making sure that what she does and how she behaves fits with a way that will protect the royal family.” Gouramma tried to run away several times as a teenager, and Atwal says that the young princess felt very misunderstood—another parallel with the modern-day Meghan.

Queen Victoria also tried, unsuccessfully, to matchmake Gouramma with another ward of the Empire she had a close relationship with—Maharaja Duleep Singh, who converted to Christianity and settled in the U.K. in 1854 at the age of 16, after he was removed from his title in the Punjab, northern India. The Queen became godmother to Duleep Singh’s children, including Sophia Duleep Singh, who would later become a suffragette.

In the 1860s, Victoria became the godmother of two more children: Prince Alamayu, son of the Emperor of Abyssinia, and Albert Victor Pōmare, who was born in England in 1863 when a group of Maori people visited as part of a trip organized by a Wesleyan preacher. The children lived with other families or “caretakers”—including members of the upper middle class in the case of Gouramma, the family of the naval captain the case of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, and an army officer in the case of Alamayu. Victoria also played a role in directing their education and comportment, or behavior, training. “There was an element of sympathy—[Victoria] saw them as kin really, in many respects, they were royal, and they were Christians,” says Atwal.

Control of the Royal Family’s image

Part of the reason why these children were taken under Victoria’s wing was because the British Royal Family was projecting a new image for themselves, not only within British society, but across the Empire, says Atwal. Much of the way we understand the Royal Family today, as a public-facing family and in its relationship with the media, was consolidated during the Victorian era, alongside the development of photographic practice and mass printed media.

As has been well documented, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert started the concept of the royal family photo album as photography became more technologically advanced; Victoria was particularly fond of the medium. Within these albums were photographs of their wards, including Gouramma and Sarah Forbes Bonetta. “So in a way, they see each other as family, even if they were adopted members of the family,” says Atwal. These photographs contributed to the public image of the monarchy, and ultimately projected one that was a “squeaky clean model royal family,” she says, adding that the monarchy’s status has become more dependent on public opinion over time, and so the need to protect that image has become more important. “Everything has to work in the benefit of the monarchy, the crown and the British royal family. That has been a consistent theme throughout history, especially recent history.”

And when the godchildren fell out of favor or did anything to tarnish that model image, they would incur the wrath of the printed press of the era too. By the 1870s, Duleep Singh’s finances were dwindling from years of living a lavish lifestyle, and his increasing anger at the annexation of the Punjab led to his plotting a rebellion against the British Raj. “When it’s reported in the press, it’s explosive, and he is vilified in the British media,” says Atwal, who is currently researching Duleep Singh’s life. Cartoons ridiculing him appeared in the press, leaning into colonial tropes and propaganda to portray him in a negative light.

“In terms of the racism and the history and the tropes thrown at [Meghan], it originates in that earlier period,” says Atwal. She says that these issues have been intensified by the way mass media has developed today, and how the same tropes and racist comments are then amplified on social media. “In many respects, we’re dealing with old problems that have massively expanded, because of the way that the media landscape has developed.” The tabloid press grew to become a staple of British society over the 20th century, and has been involved in several scandals and tragedies in recent decades, including the involvement of the paparazzi in the car chase that ultimately killed Princess Diana in 1997, and in the phone-hacking scandal, where several high-profile journalists were found to have hacked people’s phones for information, including members of the Royal Family.

For Atwal, the fact that there has been much surprise, and interest in general, in response to her Twitter thread proves how much of this history has fallen out of public consciousness. “It just goes to show that within the wider knowledge of the history of race and Empire, we’ve got a long way to go.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com