Around this time last year, as COVID-19 shook New York to its core, the class stratification that had shaped city life for decades suddenly took on a devastating new resonance. Many of the rich, in a place that was, as of 2019, home to 380,000 millionaires, fled to luxurious second homes. Office workers logged on from cramped apartments, paying bills but struggling to balance professional duties with childcare needs or to manage loneliness, anxiety, cabin fever. Their younger colleagues and other recent grads moved back in with parents indefinitely. But, predictably, poor and working-class residents—many of them immigrants and people of color—bore the brunt of the pandemic’s horrors. They prepared the takeout, delivered the packages, sanitized the public spaces and provided the patient care their fellow citizens relied on. Their reward for protecting their privileged neighbors, in too many cases, turned out to be unemployment or illness, if not death.

Whether you think of them as heroes or you find it naive to imply that they were working out of pure generosity rather than existential need, it is quite obviously these New Yorkers, and their counterparts in cities around the world, who populate the most crucial stories of the pandemic. Yet, for months now, when primetime TV has taken on the pandemic, it has mostly been through lockdown tales that center on more fortunate groups. Comedies like ABC’s Connecting… and the CW’s Love in the Time of Corona mirrored the monotony of middle-class domestic life: Zoom happy hours, awkward attempts at remote dating, vacation plans made and scrapped because someone broke quarantine. In the Netflix anthology series Social Distance, episodes about business owners and white-collar types vastly outnumbered episodes about frontline or low-wage workers. HBO’s COVID Diaries NYC, a bracing special that will air March 9, is a long-overdue antidote to such navel-gazing fluff.

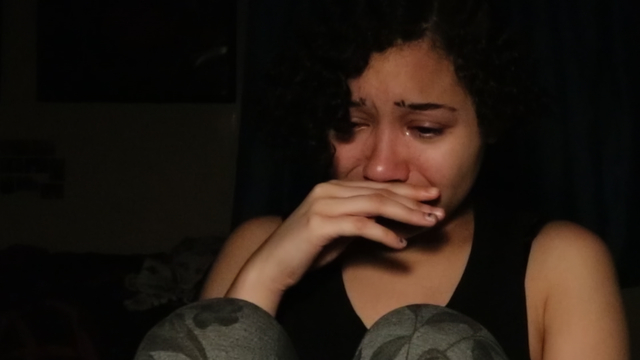

The 40-minute program collects five short documentaries shot by New York filmmakers between the ages of 17 and 21 during the early months of the pandemic. And they’re so much more than portraits of Zoom fatigue. Aracelie Colón’s intimate “My COVID Breakdown” braids together Colón’s preexisting mental health struggles with her postal-worker dad’s increasing exposure to the virus. The self-explanatory “When My Father Got COVID” finds Camille Dianand, the daughter of a MTA subway mechanic, reckoning with the potentially grim implications of such a diagnosis. Marcial Pilataxi’s comparatively slight but still affecting “The Only Way to Live in Manhattan” captures the liminal existence of his grandmother, who, as the superintendent of an expensive apartment building, earns her keep by “touching other people’s garbage.” In “No Escape From New York,” viewers witness a family’s abrupt ejection from the middle class. As his parents’ jobs in restaurant management and early-childhood education shut down, Shane Fleming follows them, camera in hand, on the desperate road trip they devise to cut costs.

Most haunting is the longest and final film in the collection, Arlet Guallpa’s “Frontline Family.” In the opening scene, the director and her mother watch an ambulance pull up to their Washington Heights building and take away one of the neighbors. A cleaning crew in head-to-toe PPE follows, to sanitize the public corridors, in a sequence of events that has clearly become a routine. Guallpa’s parents—first-generation immigrants who speak Spanish at home—are essential workers, her mom a home care attendant whose elderly patients are sometimes so cut off from the world that they don’t even know about COVID, and her dad a bus driver braving routes crowded with commuters. Shadowing them at work, Guallpa is scared and infuriated to see how little has been done to keep them safe. Turning her lens on the passengers who blithely hop on the bus maskless, she chides each one in turn: “Selfish. Selfish. Selfish.” As months pass and racial justice protests become a daily occurrence, she zooms out from her family to speak as part of a community of color that suffered so many preventable deaths.

The participants aren’t all accomplished stylists (few filmmakers are at their age), but they are effective, observant storytellers. There are indelible moments in these films. Dianand’s mother frowns worriedly, in closeup, as her father coughs offscreen. Colón’s endearingly goofy parents huddle over a pile of OTC painkiller bottles and cleaning products, taking inventory. In many cases, what we’re seeing is young people learning, in real time, a lesson their parents may have tried to shield them from in the past—the realization of how apathetic, if not cruel, society can be to those who don’t benefit from things like whiteness or a U.S. birth certificate or postsecondary education or generational wealth. To watch COVID Diaries is to confront video evidence that the novel coronavirus was never the great equalizer so many were spuriously suggesting it was during the very same months when these shorts were being made. It’s too late to prevent the hell so many families lived through last spring, but there can be no healing until the powerful understand what those beyond their own socially isolated circles have endured.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com