The Arab Spring began in Tunisia, where 28 days of protests ended 24 years of a dictator’s rule. The next day, Jan. 15, 2011, students in Yemen called for demonstrations against the strongman there. A dictator fell in Egypt, then in Libya. A change of season appeared to be bringing democracy to an arid stretch of the planet where it had never quite blossomed.

It proved a false spring. Today Egypt has a different dictator, and Yemen, Libya and Syria have wars. But read on. The passion for change—for dignity—lives on in the generation that led the way into the streets a decade ago.

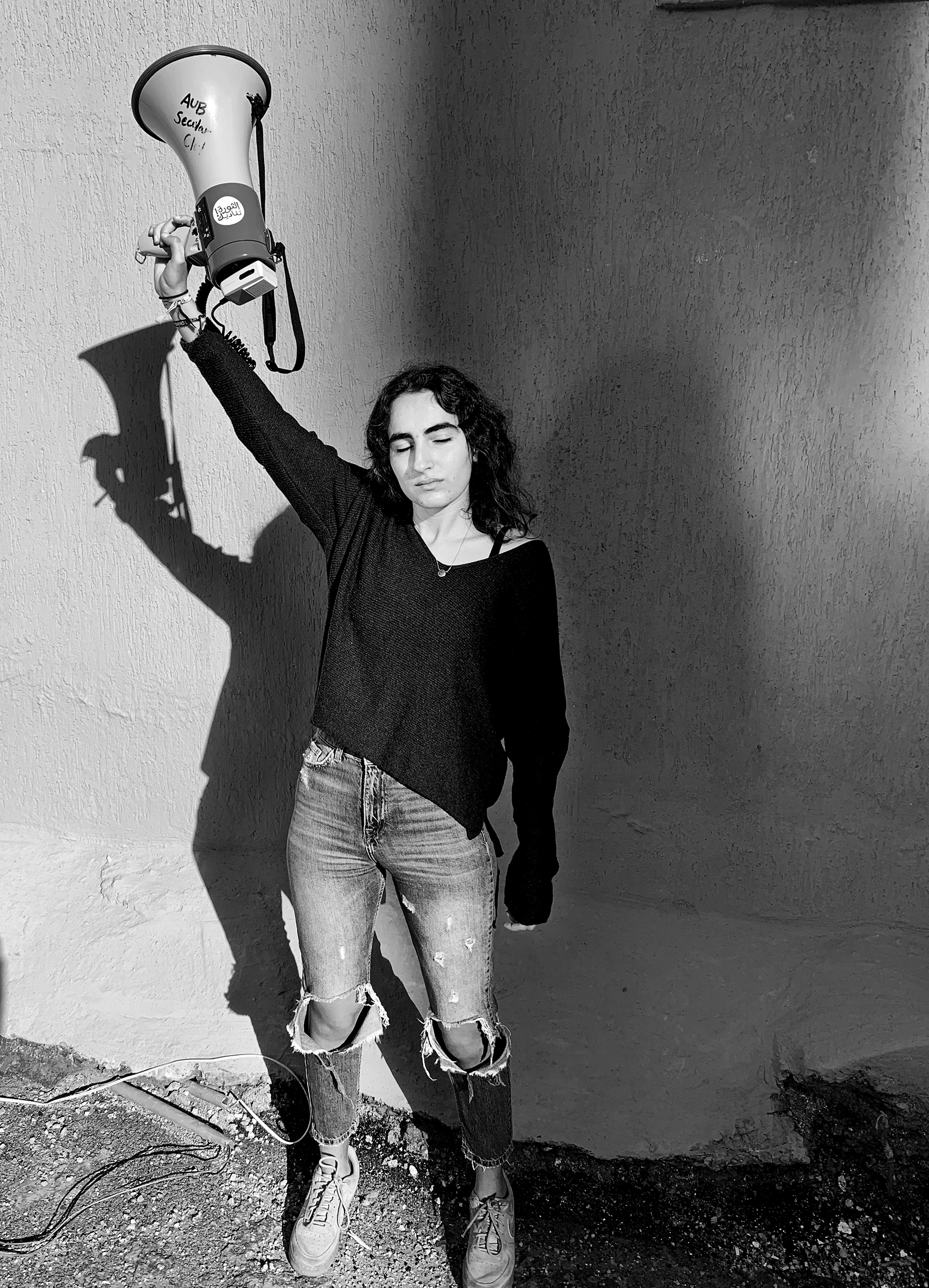

Lara Sabra, 22, Lebanon

Even before the votes had been counted, the makeshift campaign headquarters of the Secular Club near the American University of Beirut (AUB) rang with chants of “Revolution!” For the first time since Lebanon’s civil war ended in 1990, a party not affiliated with the country’s sectarian rulers was about to win student elections.

“I never imagined we would win the number of seats we did,” says Lara Sabra, the club’s president. “Even though the political ideology of the club has become more popular now, it was still surprising.” It was also a trend. Independents won 4 of 9 seats at Rafik Hariri University, 14 of 30 at the Lebanese American University and 85 of 101 at St. Joseph University.

Student elections in Lebanon—where there is no reliable polling—are often seen as a bellwether of national sentiment. They can also be volatile affairs: they did not take place at AUB through Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, during which its campus was shelled. As recently as 2007, four students were killed in armed clashes after an on-campus political dispute at the Beirut Arab University.

The 2020 elections came amid widespread disillusionment with Lebanon’s sectarian politics. More than half the nation’s population is now in poverty, and in December its currency was worth 20% of its value a year before. Even before government neglect of stored explosives resulted in a massive blast in August that killed more than 200 people, young demonstrators who’d first assembled nearly a year earlier, in October 2019, were demanding the resignation of all political representatives. Sabra says the patronage-based system that characterizes Lebanon’s national politics had also bled into student politics. Campus politics have in the past been “transactional,” with the established parties “trading previous exams or test banks, which are not widely available, for a vote,” she says.

What might these changes in campus politics portend for Lebanon’s parliamentary elections, scheduled for 2022? Only one independent candidate won in 2018 elections, as voters remained true to the sectarian system they also blame for the country’s descent. The voting age, at 21, and lack of a unified opposition pose a challenge, says Sabra.

Her own engagement in politics began in high school, when she set up a feminist club that successfully petitioned the school’s dean to revise a sexist uniform policy and led a campaign raising awareness about rape culture. At AUB, she found the Secular Club brought feminism together with causes like environmentalism and democratic rights.

But Sabra says what galvanized her was seeing Martyrs’ Square in Beirut on Oct. 17, 2019, packed with protesters who returned week after week. “I’d imagined it, but I didn’t think it could happen,” she says. “That moment made me think about politics in a different way; it showed me that it’s possible for political change to happen.”

Ali Mnif, 34, Tunisia

As his older siblings had already done, Ali Mnif was preparing to leave Tunisia in late 2010, when a vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after being humiliated by city officials. Tunisians responded by marching so insistently against the indignities of corruption, joblessness and lack of political freedom that President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali up and fled. “I stayed because of that moment. Because, for the first time, we were empowered,” Mnif recalls. “We never expected [Ben Ali] to leave. Never.”

With free and fair elections, Tunisia is the one “success story” of the Arab Spring. But Tunisians constituted the single largest group of fighters that joined ISIS’s self-declared caliphate. In 2019, 85% of the unemployed were under 35. Since 2011, some 100,000 people have moved abroad.

“We kept asking ourselves: Is the only way for us to express ourselves again to leave the country?” says Mnif, who stayed and, with several of his contemporaries, set about analyzing the bottlenecks holding back entrepreneurial Tunisians. Two years of painstaking research later, Tunisia’s Startup Act was born: a package of 20 guidelines aimed at making the business environment more transparent and meritocratic. Passed nearly unanimously in April 2018, the law is “one of the most progressive of its kind in the world,” says Mohamed El Dahshan, a development economist affiliated with London’s Chatham House.

Passage came with a favorable alignment of several factors, all of which flowed from the revolution. Tunisia’s youngest-ever Prime Minister, Youssef Chahed, then 42, was in power; the Islamist Ennahda Party’s Minister of Communication Technologies and Digital Transformation was on board early; and a month before municipal elections, nobody wanted to be seen blocking young people’s prospects.

Mnif acknowledges that most of the Startup Act’s benefits will accrue to university graduates rather than Tunisia’s working class. Still, the reforms have already borne fruit. Tunisia has registered some 380 new startups under the act. Established startups have also benefited, like InstaDeep, founded by Tunisians and headquartered in London, which just signed a deal to build a joint lab with Germany’s BioNTech, which developed a COVID-19 vaccine with Pfizer; and Franco-Tunisian nextProtein, which is pioneering insects as a food source.

In 2013, Mnif wrote an essay about what his generation would have to give up for Tunisia. “People understood that sacrifice in different ways: some sacrificed by going to Syria; some crossed the Mediterranean,” he says now. “For me, trying to rebuild the institutions of your country: that’s the biggest sacrifice you can make.”

Nada Majdalani, 36, Palestinian Territories

On a hot summer’s day in 2017, the family of a 5-year-old boy named Mohamed al-Sayis took a trip to the beach to escape the harsh realities of life in Gaza. His parents did not realize that a nearby stream flowing into the sea was full of raw sewage. That evening, the whole family fell ill—and within 10 days, Mohamed was dead.

So began the speech that Nada Majdalani, the Palestinian director of Eco-Peace Middle East, gave in May 2019 at the U.N. Security Council. Seated between the organization’s Israel director and its Jordanian director, she explained how the sewage that poisoned Mohamed forced Israel’s Ashkelon desalination plant offline—choking 15% of Israel’s water supply. It was a stark illustration of what connects three jurisdictions so often at odds.

“I see our region like the Titanic,” Majdalani says. “There are people sitting in first class with the champagne and the ballrooms, and people who are at the bottom of the ship. But once the iceberg hits: everybody sinks.”

EcoPeace is a joint Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian initiative formed in 1994, a year after the signing of the Oslo Accords, which left water as a final status issue to be resolved. Eco-Peace began addressing it immediately. The group’s landmark achievement is persuading all three governments to begin removing pollutants from the Jordan River, and Israel to release more water into the depleted river from the Sea of Galilee. Across the Mideast and North Africa, inadequate supply of water and sanitation costs around $21 billion per year in economic losses, according to a 2017 World Bank report. Analysts increasingly view environmental stress as a factor in social unrest and war.

Wim Zwijnenburg, a project leader for the Dutch peace organization PAX, says that although the relationship between climate change and conflict is complex, there’s a “mutually enforcing dynamic” between the two. “Wars and armed conflicts result in the large-scale destruction of natural resources such as forests and water sources while also eroding state infrastructure that upholds environmental protection.”

Disputes over control of the Jordan River’s water contributed to the outbreak of the Six-Day War in 1967, the year Israel began occupying the Palestinian territories. In 2020, President Trump’s so-called Middle East peace plan, which tilts heavily toward Israel, threatened a planned memorandum of understanding by alienating both Palestinians and Jordanians. “Just when we were reaching the point where we could actually put the three governments together to sign, the geopolitical realities prevented that from happening,” says Majdalani.

The political logjam led Majdalani’s team to redouble approaches to the private sector. So far, feasibility studies for two Palestinian projects, two Jordanian projects and two cross-border projects have been completed.

And in December, EcoPeace launched its most ambitious initiative yet: a regional master plan called a Green Blue Deal for the Middle East. Inspired by the Green New Deal proposed by progressive U.S. lawmakers and the European Union’s landmark $572 billion green spending plan, it is “a repackaging of what Eco-Peace is already doing on the water-energy nexus,” Majdalani says.

At the Security Council, both the Israeli and Palestinian ambassadors commended Eco-Peace. “I walked out that day very proud of what we do,” she says. “It made me feel that everything might be possible.”

Mohamad Najem, 39, Lebanon

When Jordanian police forcibly dispersed protests over teachers’ pay in July, arresting all 13 board members of Jordan’s Teachers Syndicate on dubious grounds, they also beat journalists covering the demonstrations. Just as videos of those beatings began to circulate online, Facebook Live mysteriously stopped functioning.

It was not the kind of thing Mohamad Najem saw himself probing in 2008 when he co-founded Beirut-based SMEX, a nonprofit aimed at coaching bloggers to capitalize on emergent social media platforms. But as the region’s governments reached deeper into the cyberspace that had once provided sanctuary for dissidents, Najem’s work expanded to meet them on the new battleground.

In the case of the Jordanian protest, it turned out to be the government, not Facebook itself, that had blocked access to Facebook Live. But in June, SMEX got to the bottom of Facebook’s removal of footage of another protest: a rare anti-government demonstration in southwest Syria. A U.K.-based company with links to Syria’s Assad regime had “mass reported” videos of the protests, claiming they infringed on a copyright it held. SMEX’s investigation found that company had purchased the license to that footage from an undisclosed third party in the region. After a call with SMEX, Facebook removed the company’s copyright privileges and took steps to make it more difficult for others to purchase such licenses. “Facebook responded, and we fixed that problem,” says Najem. “But … the companies should have already been on top of it.”

During the uprisings of a decade ago, social media platforms were crucial for protesters, who used Facebook and Twitter to publicize outrages and call people to the streets. Today, authoritarian governments use their power to inhibit dissent and track down critics on the same platforms. Social media firms that basked in the image of freedom are, in fact, businesses obliged to operate under the laws of any country where they operate. “We are in a situation where the companies who boosted free expression in our region are the same companies who are now throttling and censoring a lot of the content that is speaking truth to power,” Najem says. He notes that it wasn’t until 2014 that Facebook employed a head of policy for the region. And as with Google and Twitter, its regional headquarters is in the UAE, an absolute monarchy with an exhaustive record of suppressing dissent domestically and through the region. “It’s no secret that a Saudi mole operated inside Twitter for several years,” says Najem. “If the Saudis can do that at Twitter’s office in Silicon Valley, imagine how much easier it is for Saudi Arabia or the UAE to do it in Dubai.”

In early 2020, Syrian activists launched a campaign to denounce Facebook’s decision to disable thousands of anti-Assad accounts and pages that had documented war crimes since 2011, under the pretext of removing terrorist content. In June, Facebook took down more than 60 accounts of Tunisian activists, journalists and musicians on scant evidence, according to an open letter signed by SMEX and scores of other civil-society groups in the region; and last October, Twitter suspended en masse the accounts of Egyptian dissidents living in Egypt and across the diaspora, immediately following the eruption of anti-Sisi protests in Egypt.

Meanwhile, governments in the Middle East broaden cybercrime and terrorism laws to shrink the space available for dissent. In 2020 alone, Turkey arrested hundreds for “provocative” Facebook posts about COVID-19. Voicing support online for Qatar can warrant a jail term of up to 15 years in its rival, the UAE. Saudi Arabia has become notorious for deploying state-backed “troll armies” to overwhelm criticism and threaten dissidents. And since 2019, simply following a dissident on Twitter is punishable by up to five years in prison in Bahrain.

Bahrain’s new law is just one of hundreds tracked by Najem’s largest initiative to date. Launched in 2019, SMEX spin-off Cyrilla comprises a visual database of new laws either passed or under consideration around the world that curb free expression online. Compiling the English-Arabic language database is only the first phase, Najem says—the second is to build legal cases to challenge the application of censorious laws in court.

Najem laughs about the archaic sound of SMEX, an acronym for the Social Media Exchange. More apt is Bread&Net, the one he gave its annual digital “unconference,” which since 2018 has brought together hundreds of the region’s journalists, hackers, human-rights experts and policy-makers to discuss privacy, digital security and surveillance in the region. Bread&Net expresses how fundamental the Internet is to everyday life. Despite the increasing constrictions, Najem says he’s optimistic because there’s greater awareness of the urgency to push back.

“In countries where there’s no democracy, there’s no concept of civic space,” he says. “The online space is really the only one people can use to express themselves—to do anything.”

Shaimaa, 23, Iraq

“Everyone was telling me that I should respect him and always say yes to him,” Shaimaa says of the abusive husband she married in 2015, at 17. “I felt like I was in a prison.”

It was supposed to be a sanctuary. Her family had arrived at Iraqi Kurdistan’s Baharka camp for internally displaced people the year before, after ISIS attacked their hometown in Iraq’s mountainous Sinjar region. As the oldest daughter, Shaimaa thought getting married at the camp would offer her relatives a semblance of stability. But when she began organizing games and activities for children, the spectacle of a woman playing such a prominent role in public life was too much for many of the camp’s 4,700 residents—not least her husband. Shaimaa had begun the work to ensure her brother, who had Down syndrome and was a paraplegic, would not become socially isolated. When he died at 11 in 2016, she was emotionally exhausted and asked for a divorce, against the wishes of her relatives. The censure only increased. Her family ostracized her and her uncle beat her, she says, “They said that as a divorced woman, I should be ashamed, I should stay indoors.”

Shaimaa refused. She wrote a story about her experiences fleeing ISIS and the violence she had been subject to in her own community, which won a prize after it was published in a Spanish-language magazine. That inspired her to interview other women and girls at the camp, serving as a bridge between them and international organizations like UNICEF. Impressed by the rapport she had built with Baharka’s children, and after Shaimaa initiated a system for women to report instances of harassment, the international nonprofit Save the Children enlisted her on local projects.

When Free to Run—a nonprofit that trains female survivors of conflict to run marathons—came to Baharka in 2018, Shaimaa was one of the first Iraqis to sign up to run. She helped recruit other women and girls, using the trust she’d built in the camp to assuage parents’ concerns over their daughters’ taking part in sports. Today, Shaimaa is a Free to Run coach, responsible for a group of some 20 women and girl runners—mostly refugees from Syria’s Daraa region. One 16-year-old girl, whose father was killed by ISIS, had been considering marrying her cousin before joining Free to Run, Shaimaa says. After participating in the program, she decided to postpone marriage and instead return to school.

“The girls really look up to Shaimaa and what she has achieved. They can see her really living what she’s sharing,” says Christina Longman, Free to Run’s country director for Iraq. A few months ago, Shaimaa moved her parents and siblings out of the camp to an apartment in nearby Baharka City. The wall behind where she takes our Zoom call is covered with certificates and medals from races she’s run—mostly 5K and 10Ks, but she hopes to complete the Erbil marathon in the future. Recently added is Beyond Sport’s 2020 Courageous Use of Sport accolade, awarded to Shaimaa for standing up to injustice and discrimination and using sports to improve her community.

“I feel free when I run, far from prisons and war,” she says. “I feel like there are no limits and nothing to stop me.”

—With reporting by Suyin Haynes, Billy Perrigo and Raja Althaibani

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Joseph Hincks at joseph.hincks@time.com