It’s a balancing act that Canberra has long pulled off deftly—to be militarily, culturally and politically aligned with Washington, while economically benefiting from America’s rival China. But the tightrope looks increasingly frayed following an all-out assault on Australia by its now estranged top trading partner. The dispute has seen billions of dollars of tariffs imposed on a third of all Australia’s exports to China in retaliation for perceived affronts.

Last month, Beijing slapped 200% tariffs on Australian wine—for which China is the largest export market—on top of new sanctions on Australian beef, coal, copper, sugar, seafood and timber. The moves follow a list of 14 grievances published by Beijing. They include Canberra’s ban on Chinese telecom giant Huawei, its introduction of measures to safeguard domestic politics from perceived Chinese interference, and Australia’s condemnation of Beijing’s treatment of Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

On Nov. 30, tensions escalated when Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian tweeted a heavily stylized image of a grinning Australian solider holding a bloodstained knife to the throat of an Afghan child. “Shocked by murder of Afghan civilians & prisoners by Australian soldiers,” he posted. (While the image was not real, Canberra’s own investigation found that Australian troops unlawfully killed 39 Afghan prisoners and civilians, sometimes in a process known as “blooding,” when junior troops were told to take the lives of captives in order to notch up their first kill.)

Read more: How Joe Biden Can Start Fixing Relations With China

Zhao has refused to remove the tweet despite Canberra summoning the Chinese Ambassador in protest and loud condemnation from Australia’s allies. France called Zhao’s tweet “shocking and insulting” to nations which had joined the U.S. in Afghanistan, while New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern vowed to raise the issue with Beijing. U.S. President-elect Joe Biden’s incoming National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan meanwhile took the opportunity to reply: “America will stand shoulder to shoulder with our ally Australia and rally fellow democracies to advance our shared security, prosperity, and values.”

Indeed, the Sino-Australian spat is now a test not only of Canberra’s resolve versus China’s economic might but also of Biden’s broader attempts to re-energize U.S. alliances after four years of Trump’s America First policy. Speaking to NBC News in his first interview since the election, Biden said: “America is going to reassert its role in the world and be a coalition builder.”

The sentiment is welcomed by Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister, current president of the Asia Society, and a Mandarin-speaking Sinophile. He says Trump’s muddled China policy “was an utterly chaotic experience for allies,” as well as having “zero material effect” in coaxing better behavior from Beijing.

China’s foreign policy and economic growth

Zhao’s tweet typifies Beijing’s assertive posture under President Xi Jinping. In recent weeks, Beijing has ramped up propaganda to challenge the overwhelming evidence that COVID-19 originated in China—sending a stern message to Canberra, which infuriated Beijing by calling for an independent probe into the origins of the virus. China also fortified its Himalayan border by building villages on land annexed from neighboring Bhutan.

After the “Five Eyes” nations—comprising the U.S., U.K., Australia, New Zealand and Canada—objected to the expulsion of four pro-democracy lawmakers from semi-autonomous Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, Zhao warned that members of the intelligence-gathering alliance risked “having their eyes poked out if they dare to jeopardize [China’s] sovereignty, safety and development interests.”

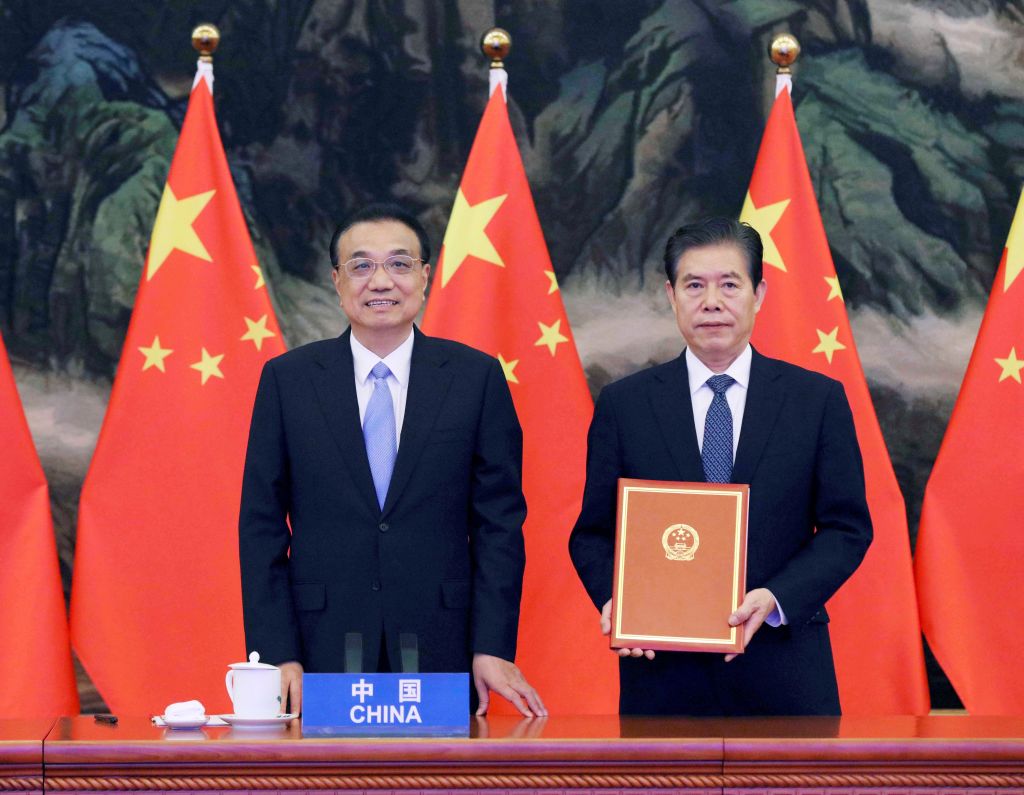

Alongside the tough talk, China is also quietly boosting its economic leverage, exemplified by its inking of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Touted as the world’s biggest free trade deal, it encompasses 15 Asia-Pacific nations—including Australia.

Just under half of RCEP signatories are U.S. allies, unable to ignore China’s economic heft when the global economy has been battered by the pandemic. While most of the world braces for recession, Chinese exports grew 21% year-on-year in November as its factories rushed to supply goods to Western countries under lockdown. Indeed, China’s economy is the only major one heading for growth this year, and Beijing is now the biggest trader, infrastructure builder and preferred lender in Africa, Latin America and Central and Southeast Asia, as well as the top trading partner for most of the Asia-Pacific region.

“China is now the biggest growth engine every year,” says Victor Gao, an international relations expert and former translator to reformist leader Deng Xiaoping. “I think Washington needs to come to terms with that reality.”

But to the contrary, Trump’s China-skeptic foreign policy team appears intent on burning as many bridges as possible before vacating the White House. Not content with a sweeping trade, tech and media war, the State Department on Dec. 4 formally ended several decades-old cultural exchange programs with China, deriding them as “propaganda tools.” On Thursday, it also announced U.S. entry visas for Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members and their families will be limited to a single entry with a duration of 30 days (as opposed to the previous option of 10-year visas).

Restoring America’s Presence in Asia

For Rudd, a coherent White House policy toward China will be one that represents the collective strength of Washington’s allies. Australia and Japan just signed a defense pact that allows their military forces to train on each other’s territory, for example. India and the U.S. have also agreed to bolster military cooperation.

He says the fact that Biden appears to be putting together a foreign policy team with deep regional experience is a good sign. “From Seoul to Tokyo, Beijing to Canberra and Delhi, the key personnel of this administration … are well-known figures in the region and well-respected as professionals and that is a critical factor.”

The incoming administration may win ground by reaffirming America’s longstanding commitment to human rights (in which department “the Trump administration was as bad as you can imagine,” says Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch). Biden could also emphasize fairness in trade by trying to revive and restore the World Trade Organization’s credibility as a forum for addressing international disputes.

Read more: We Must Set Aside Crude Nationalism If We Want to Learn the Truth of COVID-19’s Origins

Or the president-elect could simply pay visits to America’s regional friends and potential allies, undoing the negative impression Trump created by thumbing his nose at one Asian confab after another. The outgoing president’s standoffish attitude left the way open for Xi, who has aggressively courted Asian states and described the 10-member Association of South East Asian Nations as China’s “regional diplomatic priority.”

“That’s the starting point,” says Rudd. “Xi Jinping has always shown up. Trump didn’t. That’s the problem at the most fundamental.”

Fixing it ultimately means that Washington will need to make its presence felt on the ground.

“The challenge for the Biden administration,” says Rudd, “is whether they can achieve sufficient aligned solidarity, both in Asia and in Europe, to counterbalance what China believes is a balance of power shifting and inexorably in its direction.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlie Campbell / Shanghai at charlie.campbell@time.com