In the wee hours of the morning after Election Day, state officials were still tallying millions of mail-in and absentee ballots in key battleground states, and the presidential race remained too close to call. But that didn’t stop President Donald Trump from gathering his supporters in the East Room of the White House, falsely asserting he had already won, and promising he would challenge future election results in court. “We’ll be going to the U.S. Supreme Court,” he said. “We want all voting to stop. We don’t want them to find any ballots at 4 o’clock in the morning and add them to the list.”

By the time the sun had risen, the Trump campaign had taken its cue, with top advisers calling for multiple lawsuits on the grounds that the ongoing vote count would result in tallying “illegally cast ballots.” In a recording of a Nov. 4 phone call with supporters obtained by TIME, campaign aides forecast legal challenges in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. By late that afternoon, the campaign had demanded a recount in Wisconsin, filed suit to stop the ballot count in Michigan, and launched two more legal challenges questioning the ballot-counting process and voter-ID laws in Pennsylvania. It also filed a motion to intervene in an existing dispute over Pennsylvania ballots at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Election-law experts from both sides of the aisle dismissed the Trump team’s suggestion that the ongoing vote count was untoward. State election officials routinely take days to finish counting ballots, and with more than 90 million Americans requesting mail-in ballots because of the pandemic, delays were widely expected. “It’s contrary to law and the way we run elections to suggest we should stop counting votes because one of the candidates is ahead and doesn’t want to fall behind,” says Trevor Potter, former general counsel for John McCain’s presidential campaigns.

But with relatively tight margins in key battleground states, including Pennsylvania, Nevada and Georgia, it was also immediately clear that an onslaught of election-related litigation was all but inevitable. It is no longer a question of whether the results of the 2020 presidential race will end up mired in the courts; it is how long and how consequential that court battle will be.

The contours of the coming fights are only beginning to emerge. Experts say that in coming days, new cases could hinge on anything from recounts to obscure state statutes to whether the U.S. Postal Service delivered ballots.

The Biden campaign’s legal team has been sanguine about the deluge to come. “Let me tell you this: if you go to the Supreme Court today, drive around the building, you will not see Donald Trump, and you will not see his lawyers,” says Bob Bauer, former White House counsel under Barack Obama and a senior adviser to the Biden campaign. “He’s not going to the Supreme Court of the United States to get the voting to stop.”

But at least some top Republicans, including Tom Spencer, who worked for George W. Bush in Bush v. Gore, the case that decided the 2000 election, foresee the legal wrangling ending at the court, where Trump has appointed three of the nine Justices. He predicts that the outcome may hinge on three Justices—Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts and Amy Coney Barrett—all of whom, like Spencer, worked on Bush’s team two decades ago. In September, Trump said he wanted Barrett installed on the high court before the election to ensure a full bench to decide election disputes. “The big issue of course is how is Justice Barrett going to rule,” Spencer says.

The consequences of the coming legal battles may extend beyond who becomes the next President of the United States. The litigation could test Americans’ confidence in the electoral process, shake their faith in the judiciary as an impartial arbiter of U.S. law, and further divide an already polarized nation. “Make no mistake: our democracy is being tested in this election,” Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf said Nov. 4. “This is a stress test of the ideals upon which this country was founded.”

Lawyers for both the Trump and Biden campaigns have been preparing for this moment for months. With backing from deep-pocketed donors, as well as the Republican and Democratic National Committees, each has amassed an army of top-tier lawyers and legal experts who have been deployed at strategic outposts around the country. In the months before the election, lawyers for various Democratic and Republican entities filed more than 400 election-related lawsuits, putting the 2020 race on track to be the most litigated in history.

Some of these decisions may have made a post–Election Day showdown more likely by narrowing the margin between Biden and Trump. On Oct. 26, the Supreme Court upheld Wisconsin’s ballot-receipt deadline. Appeals courts similarly ruled in favor of shorter ballot-receipt deadlines in Georgia and Michigan. The Supreme Court decision in the Wisconsin case “unquestionably” made the margin closer, says Jay Heck, executive director of Common Cause in the state. “There are probably thousands of absentee ballots that will be [arriving] in the next few days.” When the deadline was extended during Wisconsin’s primary this year, the state’s election commission said it resulted in an additional 79,000 ballots being counted.

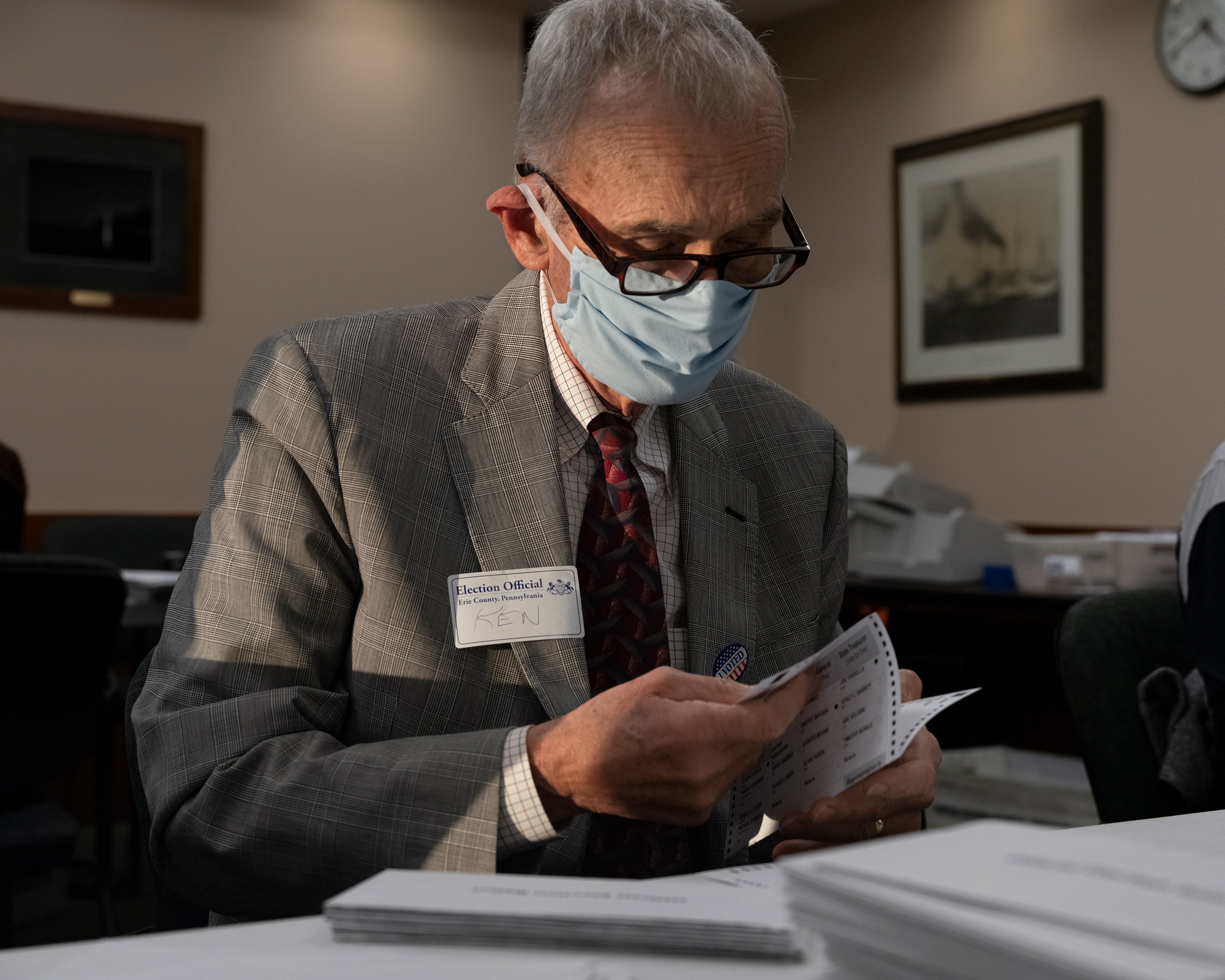

The lawsuits have only just begun. On Nov. 4, Bill Stepien, Trump’s campaign manager, noting the close margins in Wisconsin, called the state “recount territory.” “There have been reports of irregularities in several Wisconsin counties which raise serious doubts about the validity of the results,” he said. Pennsylvania is also likely “ground zero” for coming election-related litigation, experts say. The commonwealth’s 20 electoral votes make it the biggest prize of all the remaining battleground states, and its decision to expand access to mail-in voting for the first time this election cycle opens the door to lawsuits. The two lawsuits filed by the Trump campaign on Nov. 4 are likely just the beginning.

The state has already been the target of multiple Republican-backed lawsuits, with mixed results. In mid-September, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that mail-in ballots could be accepted through Nov. 6. Republicans tried twice to get the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene, and while the Justices declined to rule, they left open the possibility of hearing the case at a later date. If Pennsylvania is very close, says Potter, lawsuits are much more likely to occur because “both candidates will be fighting over which ballots to count.”

Pennsylvania’s election officials also recently ordered ballots arriving after 8 p.m. on Election Day or without definitive time stamps to be “segregated” from the rest of the ballots—a move that, election experts say, suggests they are anticipating a postelection legal challenge to such ballots. On Election Day, local Republicans filed suit challenging the commonwealth’s rules allowing voters to recast ballots after their first ones were disqualified.

As the lawyers sharpen their arguments, they are most certainly looking at how judges on both the appellate courts and the U.S. Supreme Court have ruled. In prior preelection cases, judicial opinions have most often rested on one of two principles. The first is that courts should not make decisions that change the rules of voting and ballot counting too close to an election, to avoid confusing people. The second is that state legislatures—not judges—should determine election laws, even if those laws may result in some voters not having their ballots counted. “Federal courts have no business dis-regarding those state interests simply because the federal courts believe that later deadlines would be better,” Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote on Oct. 26 in a controversial opinion upholding Wisconsin’s Election Day deadline for receiving mail-in ballots.

Democrats and voting-rights activists, along with dissenting judges and Justices, argue that courts should make decisions that encourage enfranchisement, especially during a global pandemic. Chief Justice John Roberts has staked out the middle ground, arguing that state courts can interpret state laws but that federal courts should stay above the fray.

Amid all the Solomonic parsing, good news may yet await Americans who are eager to see a quick, clean resolution to the presidential race. For one, the incoming litigation from the Trump and Biden campaigns may be moot if the final vote tallies aren’t razor thin. Even if a court rules on a case that results in thousands of ballots being invalidated, it may not change the final result. “We still have votes to count,” says Edward B. Foley, an election-law expert at Ohio State University. “It’s still possible the margins of victory in all the battleground states are decisive enough that it’s not going to be Bush v. Gore–type litigation.” It’s also possible important cases may be resolved quickly at the local level. That would prevent lengthy, high-profile fights at the Supreme Court that could tarnish the credibility of the election’s outcome.

Even if the fight does go up to the Supreme Court, there’s a clear end in sight. Under U.S. law, state electors are presumably valid if chosen by Dec. 8, and electors meet to cast their votes on Dec. 14. On Jan. 6, the newly sworn-in Congress counts the results and the Vice President pronounces them official. Which means even this unusually partisan and unruly moment in American democracy could help underscore one still reliable truth: all the bluster and litigiousness in the world can’t displace the rule of law. —With reporting by Charlotte Alter, Currie Engel and Julia Zorthian/New York and Tessa Berenson and Vera Bergengruen/Washington

This appears in the November 16, 2020 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com