President Donald Trump commanded an early lead in Michigan on Nov. 3, only for Joe Biden to gain the advantage the next morning. The opposite was true in Ohio: Biden appeared ahead right after the polls closed on Election Night, only for Trump to overtake his lead around 10 p.m. What gives?

While the President raged about the disparities on Twitter, baselessly insinuating that the whiplash was the result of fraud or malfeasance, the real answer is simple: mail-in ballots are counted at different times, and at different rates, in different states. In Michigan, Trump appeared to be ahead among ballots cast in person, but when mail ballots were tallied, that lead evaporated. In Ohio, Biden appeared to be ahead among mail ballots, but when in-person votes were chalked up, that lead vanished.

This election cycle, Democrats were much more likely than Republicans to vote by mail. That’s largely due to Trump, who spent months bashing mail-in voting and urging supporters to vote in person instead. Many appear to have listened: 67% of Republicans said they planned to vote in person on Election Day, according to a Marquette University Law School poll, compared with just 27% of Democrats.

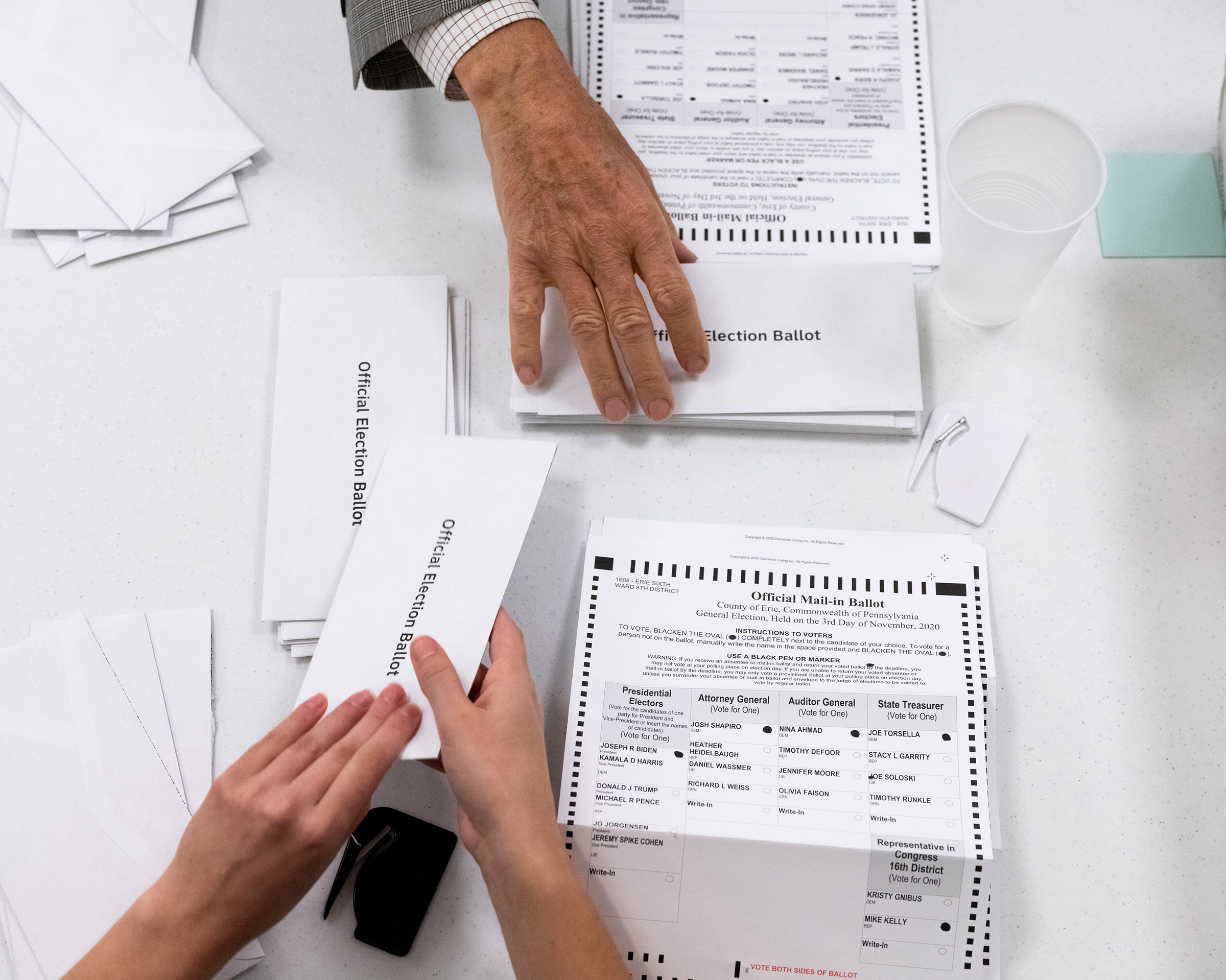

Voting by mail is a safe and secure way to cast a ballot, but counting those ballots does tend to take longer than tallying votes cast in person. In most states, election officials must remove each mailed ballot from its outer envelope and secrecy sleeve, verify the voter’s registration and signature, and then feed that ballot into a scanner. Processing tens of thousands—or tens of millions—of votes in that manner takes time. States’ rules affect how quickly mail ballots are counted, too. In both Iowa and Ohio, election officials can process absentee ballots before Nov. 3, allowing them to report those results relatively early. In other states, including Michigan, officials aren’t allowed to start processing mail ballots until Nov. 2, significantly delaying a final tally.

Pundits saw the phenomenon coming well before Election Day, dubbing it the “red mirage” or the “blue shift.” There are plenty of examples. Take Wayne County, Michigan, where Detroit is located. Donald Trump, at one point, led Biden in the state by hundreds of thousands of votes, but as absentee ballots from the Detroit-metro area flooded in early Wednesday morning, they helped Biden close the gap, reflecting pre-election polls showing Democrats were more keen on voting absentee.

Similar shifts happened in Wisconsin and Virginia. In Wisconsin, where officials aren’t allowed to process mail ballots until Election Day, Trump’s 31,000 vote lead was eviscerated around 5 a.m. Nov. 4 when election officials counted 69,000 absentee ballots advantaging Biden. The Associated Press later called the state for Biden. In Virginia, where most counties tallied in-person votes first, Trump held a lead for several hours, but as more than 900,000 mail ballots were chalked up, Biden secured a 9-point lead.

This is all normal, says Washington secretary of state Kim Wyman, a Republican whose state has been conducting elections primarily by mail since 2011. “It’s entirely possible in some states, just because of the crushing volumes that they’re anticipating, that they may take a couple of days or a week even to really get through the volume that they’re going to see,” she says. “It doesn’t mean there’s any voter fraud. It means that they’re really focusing, trying to do it right.”

Even in past election years, when COVID-19 has not driven tens of millions of Americans to cast ballots by mail, states do not certify results on election night. It takes days and sometimes weeks for officials to count every ballot, particularly those that arrive late, from absentee voters and military personnel overseas. This year, with most states expanding access to mail voting, experts expected it to take even longer. “It is very likely that it’s going to take time, and we will not have a winner on election night,” warned Sylvia Albert, the director of voting and elections at Common Cause, a nonpartisan watchdog group. Early election-night results, she predicted, would not represent “the true votes of the public.”

Trump, however, has been quick to cry foul. The day after Election Day, his Twitter feed was crammed with furious insinuations. “How come every time they count Mail-In ballot dumps they are so devastating in their percentage and power of destruction?” he tweeted on Nov. 4.

Whipsawing results on election night, combined with days of post-election uncertainty, is perhaps not the best way to project confidence in the electoral process. But, election experts point out, Republican lawmakers and attorneys have repeatedly moved to prevent the early processing of mail ballots. In Pennsylvania, for example, Republican legislators blocked initiatives to allow processing to begin early. As a result, several counties said they wouldn’t be able to begin tallying absentee ballots until Nov. 4 because their staffs are too small to keep up with in-person voting and mailed ballots. In Nevada, the Trump campaign and the state Republican Party sued the secretary of state and Clark County registrar on Oct. 23, seeking to stop the count of early mail-in ballots in the Las Vegas area. A judge rejected the request.

We can expect more incremental shifts in final vote tallies in the days and weeks to come. Many states’ rules allow mailed ballots postmarked by Election Day, or the day before, to arrive later in the month and still be counted. In North Carolina, ballots postmarked by Nov. 3 will be counted if they arrive as late as Nov. 12. In Ohio, ballots postmarked by Nov. 2 can arrive as late as Nov. 13. In Pennsylvania, mailed ballots that arrive by Nov. 6 will also be counted. (The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling on this extended deadline, but has indicated it could revisit the matter.)

In an election defined by a global pandemic, and an unprecedented number of Americans voting by mail, delays are inevitable. Ritchie Torres knows that struggle all too well. The 32-year-old Democrat beat his challengers for a congressional seat representing New York’s 15th District by double digits in the state’s June 23 primary. But it took a full six weeks for the state to certify the results. “Be patient,” he says. “Understand there’s a difference between the growing pains of vote by mail and voter fraud.” That’s good advice for every American, including the one in the White House. —With reporting by Mariah Espada and Olivia B. Waxman

This appears in the November 16, 2020 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com