Shalyse Olson knows there are risks associated with sending her children back to school during the coronavirus pandemic, but the mother of four in Salem, Oregon says virtual learning “has been nothing but frustrating and sad.”

That’s why she is among parents in several school districts around the country who are demanding a return to in-person, the latest escalation in the polarizing debate over how to educate children as it becomes clear that the pandemic is not subsiding.

Olson, whose children are enrolled in kindergarten through 10th grade in Salem-Keizer Public Schools, says she understood the need for remote learning initially, when the pandemic closed schools abruptly and forced teachers, students and parents to find ad-hoc workarounds from home. “All of a sudden it was like, ‘This will have to be good enough for now.’ And it was for a few weeks at the end of the year,’” says Olson.

“But now, others are finding ways to do this safely. And we need to get on board and catch up, or it’s going to be a hard one to recover from.”

A recent analysis of 106 school district plans by the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that just 10% were in-person at the beginning of September, but 55% of those districts are planning to be in-person by November. A recent Washington Post survey of the country’s 50 largest school districts found that 24 have resumed in-person learning for large groups of students, and 11 others plan to in the coming weeks.

Chicago Public Schools, for example, announced a phased plan for returning to school, which drew pushback from the Chicago Teachers Union, which called the plan “reckless” as cases surge in the city. But district CEO Janice Jackson said she was “not throwing in the towel on in-person instruction.”

San Francisco Mayor London Breed urged the city’s school district on Oct. 16 “to do what needs to be done to get our kids back in school.” “The achievement gap is widening as our public school kids are falling further behind every single day,” Breed said, noting that “parents are frustrated and looking for answers.”

But on Tuesday, the district’s superintendent said the schools would not reopen until 2021, citing limited COVID-19 testing capacity, the San Francisco Examiner reported.

We've seen around the country, and in almost every state, that cases are going up right now."

Such disputes are playing out across the country as parents realize that remote learning is likely to last far longer than they imagined. Some express frustration that they can go to restaurants and into shops, yet their children cannot go to classes. Others see remote learning as the necessary response to a virus that has not been brought under control.

As the Trump administration plays down the pandemic’s gravity, school districts have largely been left to figure things out on their own. (Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said Tuesday that it’s not up to the federal government to track school districts and their coronavirus infection rates.) Parents have resorted to citing individual anecdotes as evidence of the success or failure of reopening schools.

One thing they all agree on is that remote learning is filled with challenges, as students struggle to learn over computer screens and parents try to balance work with helping their children navigate online learning. Some families who can afford it have opted for private schools or homeschooling, and experts have predicted this year will only exacerbate educational inequities as rising coronavirus cases hamper efforts to get children back on campus.

“We’ve seen around the country, and in almost every state, that cases are going up right now, that we’re not quite at the peak where we were this summer, but we’re heading that way,” says Tara Smith, a professor of epidemiology at Kent State University College of Public Health, who chose remote learning for her own son, a first grader. “So to open up schools again right now, I think, is the wrong choice.”

People under 18 represent 10.9% of COVID-19 cases in the U.S., according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. Children, especially the youngest, seem to be less likely than adults to get seriously sick or die from the virus. And there is still debate over how frequently children spread the virus; recent studies and case reports provide evidence that transmission from children is possible. Teenagers are more likely than young children to be infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is why many schools have prioritized in-person instruction for the youngest learners first.

While COVID-19 cases have risen among children in recent months, it’s not clear that those infections stemmed from schools, but the uptick could reflect spread of the virus in the community at large. An unofficial dataset crowdsourced by Brown University economist Emily Oster suggests that schools tend to reflect the community rate of infection.

Information, and tracking, still lacking

During a recent briefing on school reopenings by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Dr. Wendy Armstrong, an infectious disease expert at the Emory University School of Medicine, said that was “encouraging.” But Armstrong noted the dataset is based on schools that voluntarily reported data, not a representative sample, meaning the results could be skewed toward schools that have strong mitigation strategies in place and are carefully tracking coronavirus cases.

“Without really broad national surveillance that incorporates all schools and all school systems, with the appropriate tracking in those schools — and that is lacking in a number of places — I would say we can’t know for sure,” Armstrong said. “But certainly, we have not seen a massive super-spreading event that has been obvious in the school systems.”

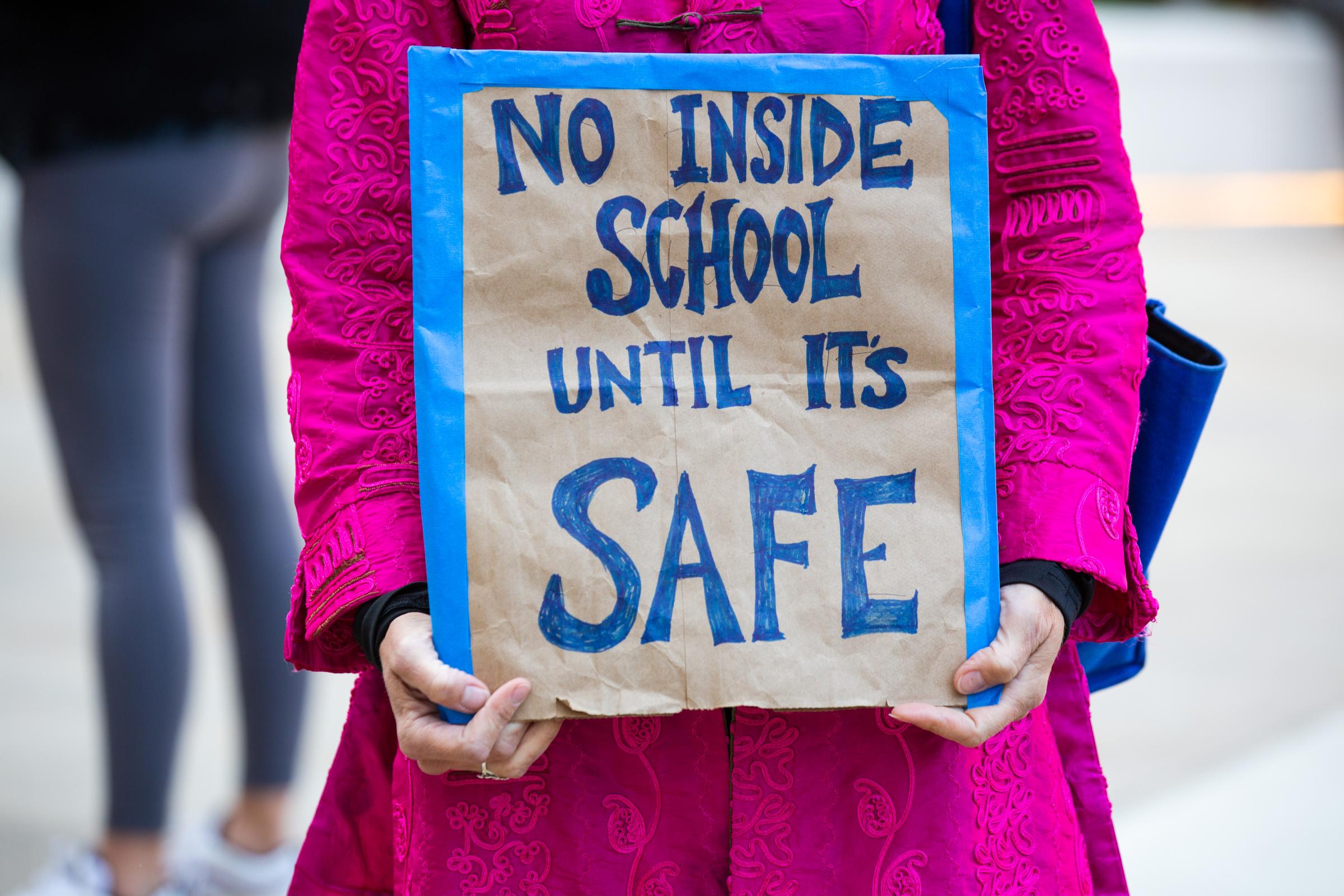

Olson, the mother in Oregon, started a petition last month, calling on state and district leaders to provide “an in-classroom learning option for those educators and families who are ready, willing and wanting to be in the classroom.” She organized rallies at the state capitol, where parents held signs that read, “School is essential,” and, “Our kids deserve an education.”

“We do not discount the virus. It’s absolutely real, and it needs to be taken seriously,” she says. “But we can’t discount education.”

Christy Perry, the superintendent of Salem-Keizer Public Schools, which serves about 42,000 students, understands why parents are frustrated, and she notes that school districts—like parents— aren’t used to dealing with such a sustained disruption to education either. “Usually an emergency is a hurricane, tornadoes, wildfires. They come, you clean up, and they go. In this case, the emergency has come and stayed,” she says.

On Oct. 13, Perry announced that the district would continue remote learning for fourth- through 12th-grade students until February 2021 because the two counties in which the district falls had not met state guidelines for reopening, with a test positivity rate of 7.6% in Polk County and 9.9% in Marion County as of Oct. 11. She’s hoping that students from kindergarten through third grade, for whom guidelines are less stringent, will be able to return to classes earlier.

“I think we do have a responsibility to get more kids back,” Perry says. “We just have to do it when it’s safe.”

Some parents are arguing that should be sooner rather than later.

Jennifer Dale, in Lake Oswego, Oregon, has held rallies calling for in-person learning because her 8-year-old daughter, who has Down syndrome, has felt isolated and has struggled to participate in lessons. She recently began going to school for two hours, twice a week, as part of the district’s expansion of limited in-person instruction.

“The importance of in-person, general education classrooms in my daughter’s life could not be more critical,” Dale wrote in an email to the director of Oregon’s Department of Education, adding: “Lizzie asks me each morning – I want to go to ‘far away school. No more computer school.'”

The problems with remote learning are especially acute for children with special education needs.

“We really feel that our kids deserve better,” says Amy Medling, who is part of a group of parents calling for in-person instruction in Nashua, New Hampshire. Her 11-year-old daughter, a sixth grader in Nashua Public Schools, has an auditory processing disorder that makes it more difficult to follow along on Zoom and decipher who is speaking, especially when multiple people are chiming in. “Pretty much we end up in tears every day at the end of remote learning,” Medling says.

Nashua School District Superintendent Jahmal Mosley says he wants to be “safe and methodical” about reopening in a city with rising transmission levels. The district has started welcoming some students back for hybrid learning in phases, starting with some special education and preschool students this month and prioritizing the youngest grades in the coming weeks. High school students would begin hybrid learning in January “if everything goes well.”

Pretty much we end up in tears every day at the end of remote learning.

Mosley agrees with parents who say remote learning is no replacement for the classroom experience, but it’s one way to keep kids learning during the pandemic. “It’s not perfect. It never will be,” he says. “But it’s a weapon against COVID-19.”

Many teachers’ unions agree and have advocated for continued remote learning, raising safety concerns about conditions within school buildings and noting that school employees, because of their ages, would be at higher risk of becoming seriously ill from the coronavirus than children.

The issue is pitting parental groups against each other in some cases. Soon after Leslie Hofmeister, who has two children in the San Diego Unified School District, and others began protesting outside the district’s Board of Education office to demand in-person learning, other parents launched a petition urging the district not to fully reopen classes until “it can be safely done using an informed, science-based approach.”

San Diego County is now seeing 7 daily new coronavirus cases per 100,000 residents, nearing the level at which the state prohibits most in-person instruction. The district is currently allowing some students with the most needs to come into schools for limited in-person instruction and is working on a plan to expand hybrid learning to all students.

“I am heartbroken for this generation of kids,” Hofmeister says, calling remote learning “an absolute disaster.” Dawniel Carlock Stewart, who has three children in San Diego schools, disagrees. “While it’s not ideal, we have certainly adjusted to the hard situation and understand that this is what’s best for everyone right now,” she says.

Carlock Stewart worries about how her children would feel if they were allowed back at school and brought the virus home to her husband, whose compromised immune system puts him at high risk of illness. “It would be more detrimental to my children and our family, ultimately, than whether or not they do well in math,” she says.

‘These families are in a bind’

Experts say the lack of national data and clear guidance on school reopenings has made it harder for parents and for schools trying to figure out the best way forward. President Trump, in his final debate with Democratic nominee Joe Biden, insisted Thursday that the virus “will go away.” “We are rounding the turn, we are rounding the corner,” he said, as daily cases continued to rise in the U.S., insisting again that “we have to open our schools.”

The result, for many parents and educators, is mass confusion.

“I think in many places, there’s probably a way to make the schools safe, but often, people don’t even agree on what safe means,” says Whitney Robinson, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health. “And another thing is that there has not been the federal funding to do things that would make all places safe.”

Smith, the Kent State epidemiologist, says the lack of sufficient testing and contact tracing still makes it difficult to determine if outbreaks are directly related to in-school transmission.

And just as Black and Latino communities have been hit hardest by COVID-19, and by its economic impact, they also have the most at stake in the schools dispute. Students of color are more likely to attend high-poverty schools, which have faced the biggest challenges getting buildings ready for safe in-person instruction or supplying students with the computers and internet access needed for remote classes. Parents of color have also been among the most hesitant to send their children back to school, in part because they have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

“I think there’s a lot of families, particularly in Black communities, Latino communities, where parents are essential workers and need to work, and not having in-person school can be a hardship,” says Robinson, who studies health disparities by race and ethnicity. “But also, these communities have seen first-hand how awful the coronavirus is.”

“So these families are in a bind,” she says.

Robinson says Congress needs to pass a relief bill that will provide more funding to school districts so they can invest in protective equipment, ventilation systems and testing to enable more schools to open in person.

“It’s doable,” she says. “We just need political will.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com