The verbal fireworks that dance through Aaron Sorkin’s newest movie, The Trial of the Chicago 7, seem too explosive to be true. The film depicts the 1969 Chicago Seven trial, in which President Nixon’s federal government charged eight anti-Vietnam war activists with conspiring to incite a riot at the previous year’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Sorkin, who has staged many tense confrontations across his career (The West Wing, The Social Network), depicts a corrupt and unreasonable judge; a parade of undercover operatives; impassioned soliloquies from lawyers; and the horrific binding and gagging of defendant Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party. TIME’s film critic Stephanie Zacharek, in her review, called it “as simultaneously entertaining and galvanizing as anything you’ll see this year.”

But while those elements may sound like inventions for Hollywood drama, they were all present, and in some cases even more exaggerated, in the real trial. In fact, the trial, which took place over five months, was far wilder than the 130-minute film, rife with scathing rebuttals, shocking courtroom violence and cameos from countercultural legends like Allen Ginsburg and Judy Collins. Here are the craziest moments from the trial that didn’t entirely make it into Sorkin’s script—or, if they did, played out with even more drama in real life than onscreen.

The incompetence of Judge Julius Hoffman

In The Trial of the Chicago 7, Frank Langella plays Judge Julius Hoffman, who presides over the trials with a gruff rigidity offset by spells of forgetfulness. At the time of the trial, Hoffman was 74 and had developed a reputation for crankiness: in Joseph Goulden’s 1974 book about federal judges, The Benchwarmers, he was described as “impetuous and rude.”

The film suggests that Judge Hoffman presided with a heavy bias toward the U.S. government, and court transcripts seem to confirm this. Time and time again, Hoffman went out of his way to constrict or alienate the defense. On the trial’s first day, Hoffman issued arrest warrants for four defense attorneys who had worked on the defense’s pretrial motions but had since dropped out of the case; he only withdrew the order after a firestorm from the legal community.

During the trial he refused to let the jury see several key pieces of evidence that would help the defendants, including a planning document in which Tom Hayden wrote that the Chicago campaign should be nonviolent. He admonished defense attorney William Kunstler (Mark Rylance), for leaning on the lectern. As in the film, he struggled with names, repeatedly getting Leonard Weinglass’ (Ben Shenkman) name wrong, calling him “Feinglass,” “Weinruss,” and “whatever your name is.”

He chided defendants for their posture; he assigned Abbie Hoffman an additional seven days in jail for laughing in court. (All in all, he assigned a staggering 175 counts of contempt, a number of which are depicted in the movie.) He told the jury to disregard Rennie Davis’ nickname “Rennie Baby,” saying, “Crowd the baby out of your minds. We are not dealing with babies here.”

Hoffman’s treatment of race

Hoffman’s flaws were perhaps most pronounced in his dealings with race and with regard to the defendant Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), a Black Panther co-founder who had little to no connection at all to the other defendants. Whenever anyone in the courtroom referenced race, Hoffman bristled: “I don’t think it is proper for a lawyer to refer to a person’s race,” he told Kunstler when the lawyer observed that only Black spectators were being thrown out of the courtroom.

Early on, Hoffman refused to let Seale either have his preferred lawyer or represent himself, and then admonished and silenced him when Seale said his constitutional rights were being violated. On Oct. 29, when Seale lost his temper and called him a “rotten racist pig racist liar,” Hoffman responded: “Let the record show the tone of Mr. Seale’s voice was one of shrieking and pounding on the table and shouting.” When Kunstler pointed out that the prosecutor Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) had also shouted, Hoffman defended him, saying, “If what he said was the truth, I can’t blame him for raising his voice.”

Shortly thereafter, Seale was dragged out of the courtroom by half a dozen marshals and came back bound and gagged. “His eyes and the veins in his neck and temples were bulging with the strain of maintaining his breath,” Tom Hayden is quoted as writing in Jon Weiner’s book Conspiracy in the Streets. “As shocking as the chains and gag were, even more unbelievable was the attempt to return the courtroom for normalcy.”

While the film depicts Schultz immediately calling for a mistrial for Seale after his shackling, Seale would in reality remain bound and gagged in court for three days. During that time, Hoffman lashed out after being accused of discrimination, saying to Kunstler, “I lived a long time and you are the first person who has ever suggested that I have discriminated against a Black man.” Seale’s trial was eventually declared a mistrial. He was convicted of 16 counts of contempt of court, leading to a four-year prison sentence, but the charges were later dismissed.

As for the other seven defendants, five were convicted for inciting riots. However, a different judge overturned all convictions partially based on Judge Hoffman’s biases, and the Justice Department decided not to retry the case.

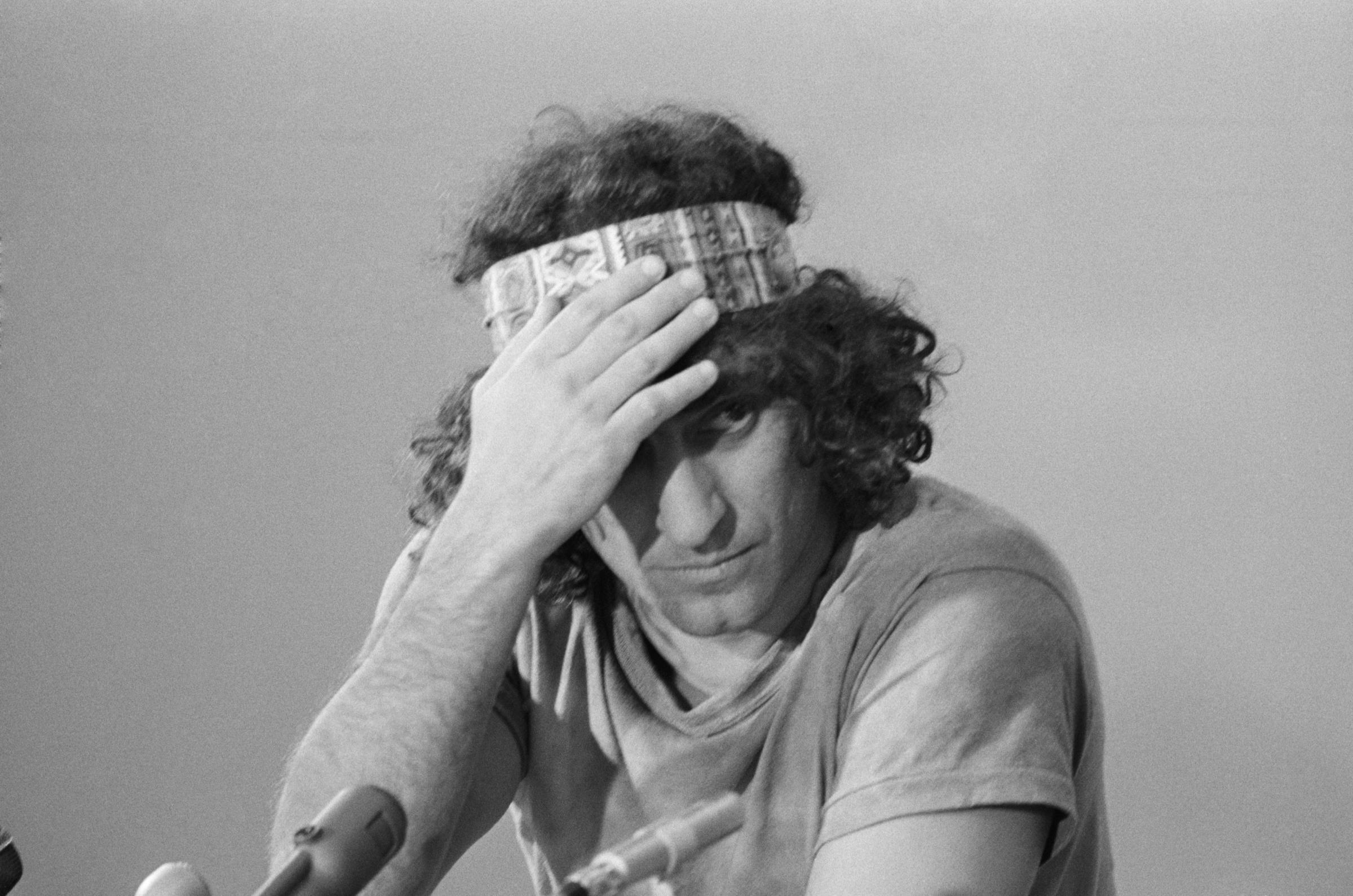

The Chicago Seven’s courtroom antics

While Judge Hoffman’s professionalism during the trial was extremely questionable, the defendants also gleefully undermined the decorum of the courtroom at every turn. The Trial of the Chicago 7 depicts Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) showing up to court in judicial robes, which they actually did. That day, Abbie also swore at the judge, who was also Jewish, in Yiddish: “You schtunk. Schande vor de goyim, huh? [You stinker, fronting for the gentiles]… Tell him to stick it up his bowling ball.”

The two Hoffmans were constantly playing a game of cat and mouse. Abbie blew the jury a kiss; the judge told the jury to “disregard the kiss.” When Abbie said he resided in “Woodstock Nation,” the judge demanded he give a “place of residence…Nothing about philosophy or India, sir.” At one point, Abbie even renounced his last name. And when he was finally sentenced and given a $5,000 fine, he called out to the judge, “Could you make that three-fifty?”

Jerry Rubin, who along with Abbie co-founded the countercultural movement Youth International Party, whose members were known as Yippies, tried to give Judge Hoffman a copy of his book during his sentencing. Reading aloud, he told the judge that he had inscribed it with, “Julius, you radicalized more young people than we ever could. You’re the country’s top Yippie.”

Reading the names of the dead

In the film’s climactic finale, Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) rebuffs Judge Hoffman’s insinuation that he will receive a lighter sentence if he shows remorse, and instead starts reading the names of the thousands of Vietnam War soldiers who have died since the trial began. While soldiers’ names were read by the defendants, it happened earlier in the trial: on Oct. 15, 1969, when Vietnam Moratorium Day was being observed by millions of Americans across the country. That day, when the defendants attempted to place American and South Vietnamese flags side by side on the defense table, Judge Hoffman unsurprisingly demanded they take them down. “Whatever decoration there is the courtroom will be furnished by the government and I think things look alright in this courtroom,” he said. Very few of soldiers’ names were said aloud before the judge cut off the endeavor.

Spitballs from the galley

Throughout the trial, the courtroom was always packed to the brim with supporters of the Chicago 7, who were more than happy to add their own commentary to the proceedings. The court transcripts include plenty of oinking, including when the judge refused to admit a cake into the courtroom for Bobby Seale’s birthday. Late in the trial, Hoffman said, “I have never presided at a trial where there was so much physical affection demonstrated in the courtroom”—to which spectators responded, “RIGHT ON!” When Hoffman ordered that all spectators leave the courtroom for the reading of the verdicts, one spectator called out, “They will dance on your grave, Julie, and the graves of the pig empire.”

Celebrity parade

The trial also included testimony from a long line of 1960s cultural icons, who were brought by the defense to describe their movement and the protests that unfolded outside the convention. The poet Allen Ginsberg, who is portrayed in the movie during the convention protests but not the trial, chanted “Hare Krishna” and demonstrated the way he chanted “o-o-o-o-m-m-m-m” during the protests, much to Hoffman’s chagrin: “The language of the United States district court is English,” he said. When Ginsberg was prodded to continue his testimony, he said, “I am afraid I will be in contempt if I continue to Om.” Ginsberg was also subject to a homophobic line of questioning from prosecutor Thomas Foran (J.C. MacKenzie), who made him read his poems that alluded to gay sex.

Phil Ochs, Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie were all brought to the stand but silenced when they started singing. (“We don’t allow any singing in this court,” Hoffman told Collins.) The writer Norman Mailer showed up to offer some poetic descriptions of the police’s aggression during the protests: “They cut through them like sheets of rain, like a sword cutting down grass,” he said.

And when the Black comedian Dick Gregory was called to testify, Hoffman hastily tried to dispel rumors of his own racism: “I would want this very nice witness to know that I am not [racist], that he has made me laugh often and heartily.”

A Sorkin-worthy monologue

Aaron Sorkin is known for writing epic, idealistic monologues for his protagonists that can sometimes verge on sanctimony. But he didn’t have to write such a speech for William Kunstler: the source material was already sterling. It’s perhaps a bit surprising, then, that Sorkin didn’t use Kunstler’s epic Feb. 2 tirade, in which he berated Hoffman for refusing to let either the activist Ralph Abernathy or Ramsay Clark, the attorney general for Lyndon B. Johnson, take the stand:

“I am outraged to be in this Court before you. I discovered on Saturday that Ralph Abernathy, who is the chairman of the Mobilization, is in town, and can be here, and because you took the whole day from us on Thursday by listening to this ridiculous argument about whether Ramsey Clark could take that stand in front of the jury, I am trembling because I am so outraged…I want you to put me in jail if you want to. You can do anything you want with me, if you want to, because I feel disgraced to be here…

I have sat here for four and a half months and watched the objections denied and sustained by your Honor, and I know that this is not a fair trial. I know it in my heart. If I have to lose my license to practice law and if I have to go to jail, I can’t think of a better cause to go to jail for and to lose my license for than to tell your Honor that you are doing a disservice to the law in saying we can’t have Ralph Abernathy on the stand…

I am going to turn back to my seat with the realization that everything I have learned throughout my life has come to naught, that there is no meaning in this Court, and there is no law in this Court.”

Sorkin skillfully replaces this dramatic climax with another narrative arc that is centered on flashbacks to when police viciously beat protesters on the streets of Chicago. It’s a far neater resolution, with the bloody visuals giving the film real-world stakes. But the court transcripts of the Chicago Seven Trial prove that sometimes history hardly needs embellishing when it comes to onscreen drama.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com