As Americans headed to the polls on Tuesday, few midterm election races were being as closely watched as the Georgia gubernatorial race. In the contest between Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican, and Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams, who would be the nation’s first black female governor, tensions have been high. Voters have reported long lines, and the close, controversial campaign means the contest may not actually be resolved on Election Day.

The debate in Georgia runs deep — and in at least one instance, offers a window into the complicated history of an issue that has divided Americans for decades.

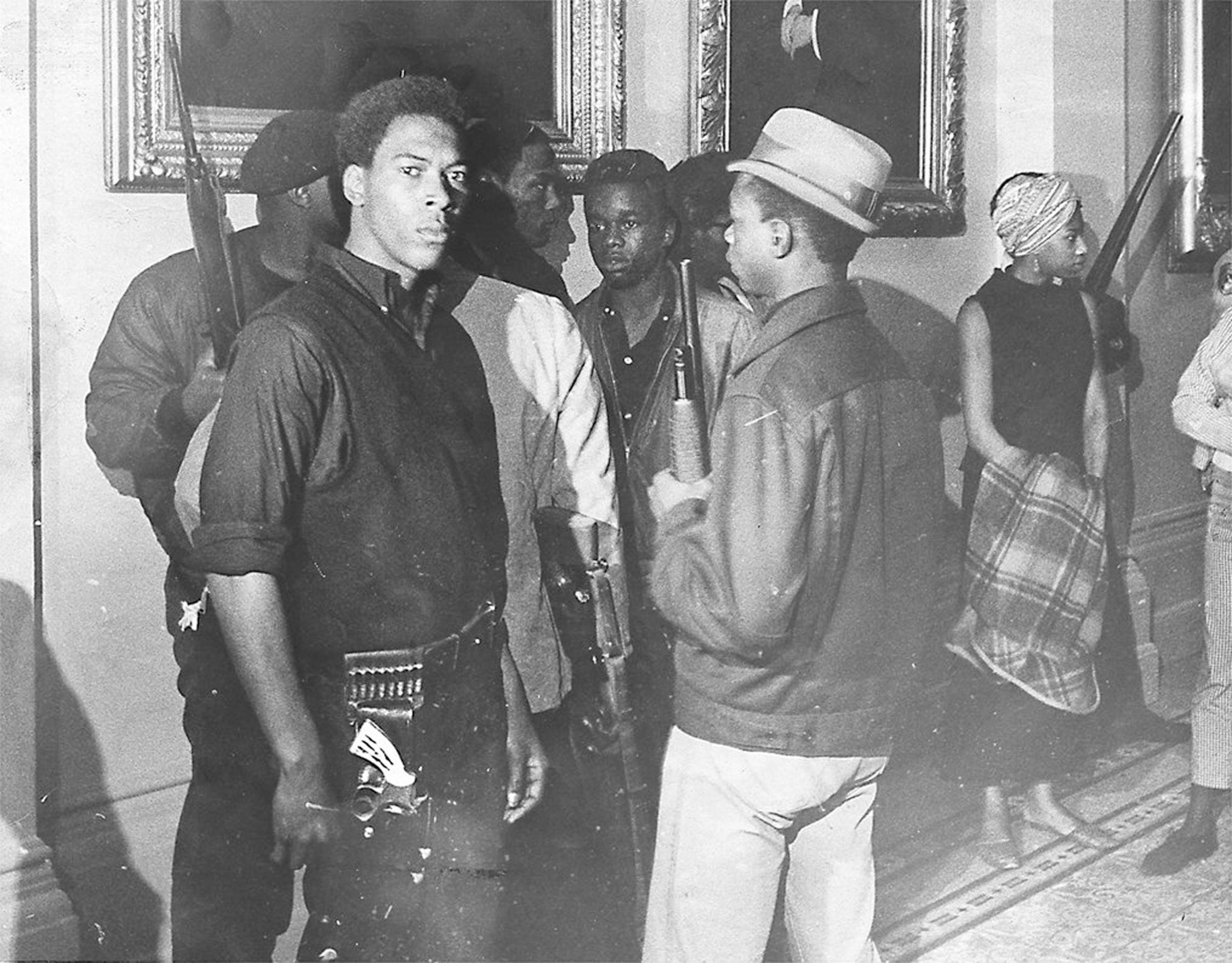

Over the weekend, Kemp tweeted a photo of heavily armed black men, members of a group known as the New Black Panther Party, holding Stacey Abrams signs. “How radical is my opponent? Look at who is backing her,” he tweeted. Though the election season has been ripe for hoaxes, this wasn’t one. On Tuesday, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution followed up with an article headlined “Those pictures of New Black Panthers campaigning for Abrams are real, and they aren’t apologizing.”

The group’s leader, Hashim Nzinga, told the news outlet that its members supported Abrams despite her stance in favor of certain gun-control reforms, even though access to weapons “is a foundation of the Panther Party.”

The New Black Panther Party group, which has been identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as an extremist group, is separate from the original Black Panther Party that was started in 1966. Nevertheless, asked on Election Day to comment on the viral image, the co-founder of the original group Bobby Seale — who dismissed the new group as “nothing but some negative crap” — explained to TIME how guns did play a key role in the early days of the activist group.

Seale and Huey P. Newton, who died in 1989, were inspired to found the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in part after the Watts Riots took place in the Los Angeles area in 1965. That upheaval began with a confrontation between a law enforcement officer and a resident, and led to more than 30 deaths; Martin Luther King Jr. said the feeling was “unanimous” that police brutality was part of the equation.

“I’m up in Oakland reading about the riot when it was happening, and I said to myself, I want to organize those black folks into a political machine,” Bobby Seale told TIME by phone. “People and the press only saw the guns, but I want to organize black folks into a political party to get more black folks concerned with our rights elected to political office.”

Seale and Newton sought to level the playing field between authorities and African Americans, so they started essentially patrolling the patrolmen. Taking advantage of California laws that allowed open carry of weapons, they offered a visual reminder of black power. Members of the Black Panthers would follow police cars, especially those known to have been involved in clashes, such as that of the policeman who fatally shot a young black man named Denzil Dowell in North Richmond, Calif., in April 1967. Experts have said the movement was one of black empowerment that represented a shift away from the nonviolence represented by civil rights leaders like King.

As the group’s original platform put it, “We believe we can end police brutality in our Black community by organizing Black self defense groups that are dedicated to defending our Black community from racist police oppression and brutality. The Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States gives us a right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all Black people should arm themselves for self defense.”

On May 2, 1967, after hearing that California state assemblyman Don Mulford was drawing up open-carry restrictions in response to the sight of armed Panthers, Seale and a group of armed Black Panther Party members headed to the state capitol in Sacramento. They made it all the way to the Assembly chamber before they were stopped. “After the state police questioned the men, they returned the weapons to them because the intruders had broken no law,” the Sacramento Bee reported back then.

Reflecting back on that day, Seale laughs.

“Why was I doing that? I was patrolling the police so we could capture the imagination of the people. And the law says I have a right to stand here and observe you,” he says. “That blew the power structure’s mind. The Black Panther Party believed in the right to self-defense from any attacks, where people would physically be attacking you. Black people are oppressed, and the police occupy our community the way foreign troops occupy a territory, and I want to defend myself from the vigilante, murderous KKK.”

Shortly after the Panthers’ stunt, California Governor and future U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Mulford Act, which put restrictions on the carrying of weapons in public. The law even boasted the backing of the National Rifle Association. Reagan said he saw “no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons,” but Seale says he believes that the legislators and advocates behind the law were specifically interested in keeping the Black Panthers from carrying guns.

Today, Georgia law does not require permits for people to openly carry guns like the ones shown in the image that spread this week.

But, even if openly carrying weapons is a key part of Black Panther history, Seale says he worries how the efforts of the New Black Panther Party efforts, which he repudiated, will be perceived. There is a time and a place for such imagery, he said, but campaign season is not it, especially given that the original Black Panther Party also aimed to elect more black officials.

“Stacey Abrams does not need those people,” he told TIME.

Georgia polls close at 7 p.m. ET.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com