“I’ve actually never liked Bly,” the chef admits to the au pair his employer has just hired as he drives them through sun-dappled emerald farmland to the country estate where she will live and work. “The people here, most of them, they’re born here, they die here. The whole town’s one big gravity well, and it’s easy to get stuck.” This is not what you would call an auspicious introduction to the place Dani Clayton has chosen, sight unseen, to build a new life. But it wouldn’t be a ghost story if it didn’t start with an unheeded warning.

The Haunting of Bly Manor isn’t just a ghost story—and it isn’t just any ghost story, either. Now streaming on Netflix, it is the eagerly awaited sequel to 2018’s surprise Halloween hit The Haunting of Hill House. Created by the streaming service’s go-to horror maestro, Mike Flanagan (Hush, Gerald’s Game), both series take inspiration from classic literature; while Hill House transformed Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel into a chilling family drama, Bly Manor updates Henry James’ fin-de-siècle gothic The Turn of the Screw (as well as a few other works by the American expat author) to the 1980s. Instead of trying to improve upon the originals, Flanagan’s thoughtful, if uneven, retellings put them on the analyst’s couch, patiently dissecting the characters and themes. In its sluggish first half, Bly Manor investigates what has propelled Dani (Victoria Pedretti, one of many Hill House actors who return in a new role), the chef (Rahul Kohli’s Owen) and the estate’s other denizens into this “gravity well” in the English countryside. As the nine-episode season continues, a better question emerges: can they ever escape it?

Framed (in a nod to James) as a yarn told at the rehearsal dinner for a present-day wedding, the story opens in London, 1987. Dani, a young teacher from the United States, blows her interview with Lord Henry Wingrave (Henry Thomas of Hill House and Better Things), a barrister, for a live-in position tutoring and caring for his orphaned niece and nephew. Later, as if by kismet, Dani spots Wingrave in a bar, accosts him and learns that the kids’ last au pair died by suicide. “I understand death,” she insists, suddenly overcome with emotion. “I know what loss is.” And just like that, the job is hers.

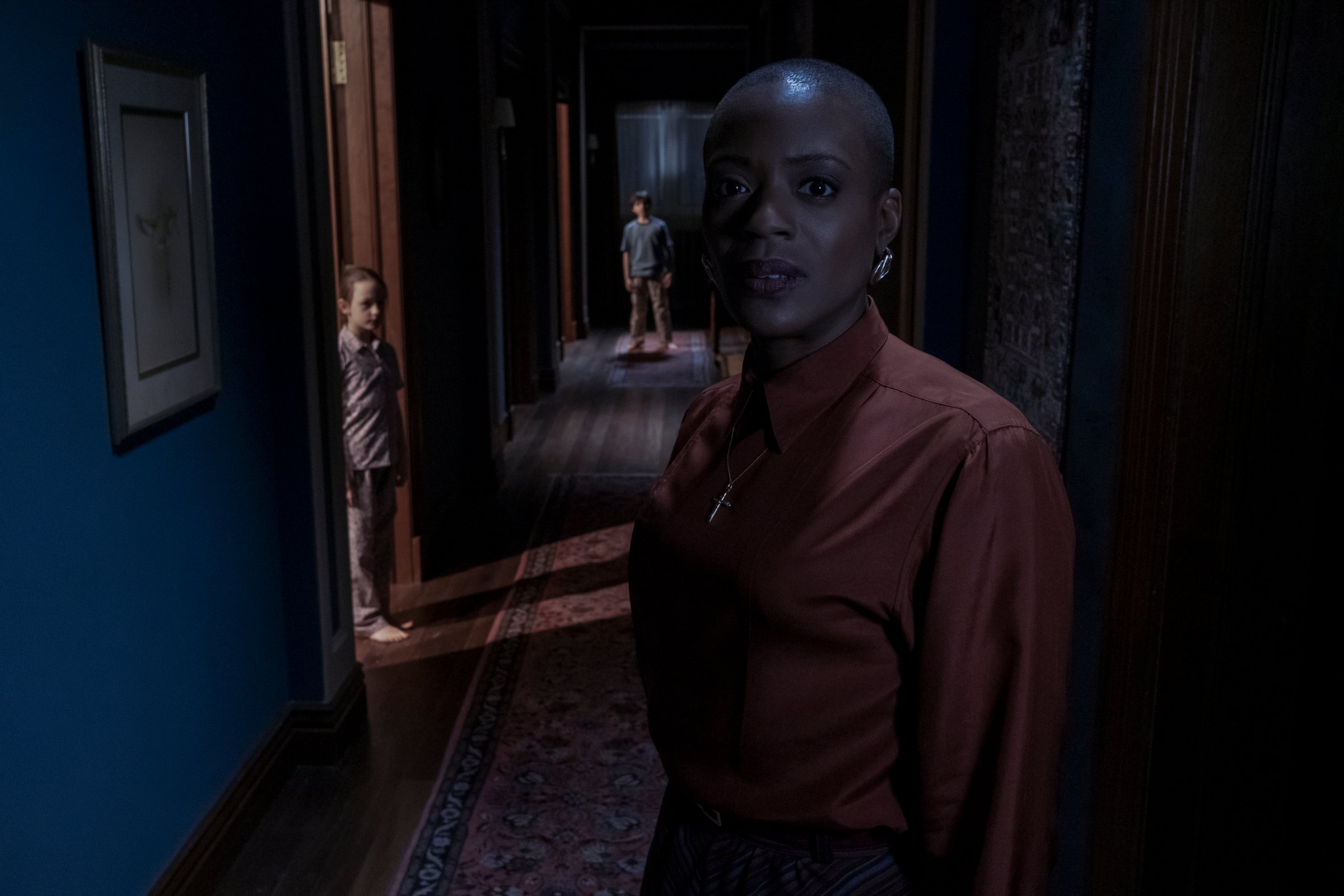

At the centuries-old Bly Manor, she meets her adorable charges, 8-year-old Flora (Amelie Bea Smith) and 10-year-old Miles (Benjamin Evan Ainsworth). While both children have the impeccable manners of the mini aristocrats they are, Miles sometimes acts disconcertingly grown-up for his age—demanding a glass of wine or touching Dani in an uncomfortably sensual way. He has recently been dismissed from boarding school, for reasons no one volunteers. Dani’s new co-workers are kind, though hints of disappointment and melancholy lurk beneath their friendly surfaces. Owen was training as a chef in France when his mother fell ill; he took the job in Bly in order to be close to her. The gardener, Jamie (Amelia Eve), is playful but closed off. A regal middle-aged woman who takes great pride in her work, housekeeper Mrs. Grose (T’Nia Miller from Years and Years, in a superb, layered performance) seems to have no life outside the estate.

It’s hard to tell, at first, whether the house is truly haunted or just permeated by death—assuming there’s a difference. Horror tropes are present from the beginning: hang-up phone calls, creepy dolls in a dollhouse that resembles Bly, figures glimpsed from a distance who may or may not be living humans. As Flanagan indulges in lengthy excavations of several characters’ backstories, a mystery slowly—too slowly—coalesces around Dani’s predecessor, Rebecca Jessel (Tahirah Sharif of Netflix’s A Christmas Prince trilogy). Beautiful, sharp and ambitious, she dreamed of becoming a barrister and hoped Lord Wingrave would help get her foot in the door. Then she fell for his right-hand man, Peter Quint (Oliver Jackson-Cohen, who played Pedretti’s twin in Hill House), a canny Irish striver who seems to have made an indelible impression on the kids. (Thankfully for those of us suffering from Stranger Things fatigue, yuppie Peter is the only character whose story line exploits ’80s nostalgia.)

Hill House fans will recognize the multiple timelines and flashbacks, which make the past as much of a mystery as the present and future. Also familiar is the sequel’s emphasis on character development, which can be hard to find in the horror genre, even if its pacing feels off this time around. Yet the two seasons are almost mirror images of one another. While Hill House excelled in its early, grounded episodes before devolving into chaos at the end, Bly Manor only gets going in a second half that, despite some distractingly soapy twists, thrives on productive confusion. And it offers a more satisfying conclusion than the first season, which not only sugarcoats but also distorts Jackson’s narrative by reducing two women’s deaths to the collateral damage of a reconciliation between an extremely unpleasant male character and his misunderstood father.

Bly Manor doesn’t replicate The Turn of the Screw’s ending, either. Its plot is much too complicated, and spans far too many years (including a stunning stand-alone episode set hundreds of years ago), for that. Its animating tension does, however, chime with the original novella—a love story as well as a ghost story, as the adaptation’s contemporary narrator reminds us, but also an allegory for class anxiety. With the children’s parents dead and Lord Wingrave vehemently opposed to any hands-on participation in their upbringings, Bly Manor confounds the rigid British class system. Miles and Flora, both too young to care for themselves, are the only upstairs to their adult employees’ downstairs. So the dangerously free servants have the run of the house. Is anyone actually in charge of this place? Or does it belong to those alleged ghosts?

Now, 122 years later, we’re well aware that class is not the only social hierarchy, and Flanagan populates his updated Bly Manor with a wider variety of outsider identities. Owen’s heritage is South Asian. Mrs. Grose is a Black woman. Rebecca is biracial. Characters scarred by their experiences with the lovers whom society deems proper for them find space, in this nonjudgmental community, for different kinds of romance. As a straight, white man in an American Psycho suit, Peter achieves the most proximity to their distant, aristocratic employer, but his accent and lack of professional connections give him away as an interloper in Lord Wingrave’s world—as “the help.” He is, in his own estimation, “quite simply not part of the f-ckin’ club.”

The mutual discomfort separating the absent rich from the forgotten poor (or white from Black, or straight from queer) is where the trouble starts. And this aspect of the show is anything but a performatively woke, 21st-century take on a 19th-century text. Flanagan is hardly the first to see in James’ novella a metaphor for the harm wrought by inequality; he just meditates on that theme. The book “exposes the cruel and destructive pressures of Victorian society, with its restrictive code of sexual morality and its strong sense of class consciousness,” the literary scholar Jane Nardin wrote in 1978. “Because the adult characters in The Turn of the Screw are trying to live by a set of social and moral norms that deny or frustrate some of the basic impulses of human nature, their good intentions turn sour and they begin to show marked signs of strain and mental deterioration.”

For the upper classes, which don’t typically abandon their kids but do outsource much of their care to servants, nannies and boarding schools, the anxiety is over the kind of values these proles will instill in the next generation. For the working class, it’s that no matter how talented they are, how hard they strive or how much they endear themselves to their supposed betters, they’re trapped within the caste they were born into. You could argue that similar anxieties are fueling unrest in our current, politically reactionary Gilded Age. And yet, now that movement between stations and identities and places is more fluid, socially if not always economically, the odds of a successful escape look more promising than they once were. In 2020, that’s where the salient story lies. Bly Manor eventually becomes a compelling revision—but only when it starts moving Dani and her companions toward the exit.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com