When Anthony Lynn, head coach of the Los Angeles Chargers, was in third grade, his world changed. He grew up in Celina, Texas—the son of a single mother, and one of the few Black kids in what was then a small town north of Dallas. A girl—Lynn thought she was cute—was handing out invitations to her birthday party one day, when Lynn noticed she skipped him and a Black girl in the class. When Lynn asked why, the response left him devastated. It’s because you’re Black and my parents won’t allow you to come to my place.

“After that moment, I never saw things the same,” Lynn, now 51, tells TIME in a video call from his office in Costa Mesa, Calif., where the Chargers are headquartered and holding training camp. “That’s when I knew the world was different. There’s a difference being Black and white. Then I started seeing color.” Lynn says this, and other experiences with racism throughout his life, helped motivated him to reach the top ranks of the NFL, where he is now one of just three Black head coaches. “I didn’t didn’t like the fact that people didn’t think I was equal, or thought they were better than me,” says Lynn. “I can’t say race wasn’t a big part of why I’m where I’m at. Because it pushed me.”

Now, the realities that Lynn confronted head-on in his life are at the forefront of his job as head coach. He sees systemic racism in the NFL, a league in which Black men are 60% of the players, but less than 10% of head coaches. He sees it in the streets, with the killing of George Floyd and the shooting of Jacob Blake. “I was like, wow, again?” Lynn says of watching the video of police shooting Blake in Kenosha, Wis. “It’s always unarmed Black men. And seven times? That just made me sad, man. I got emotional.” On Aug. 26 the Milwaukee Bucks declined to take the court for a playoff game against the Orlando Magic; other teams across sports also staged strikes, effectively shutting down the games. The Chargers were supposed to hold a scrimmage at their new home, the $5 billion SoFi Stadium, the next day. Lynn called a team meeting, and let players express their frustrations. “After that, no way could we take the field and practice,” says Lynn. “Because something was more important than football at that time.” The scrimmage was cancelled.

Read more: Why Jacob Blake’s Shooting Sparked an Unprecedented Sports Boycott

Lynn’s Chargers will kick off an NFL season like no other this weekend. In the midst of a pandemic and national reckoning on race, L.A. travels to Cincinnati to take on the Bengals and the No. 1 pick in the 2020 draft, quarterback Joe Burrow, on Sunday. While Lynn says he would have supported a player walkout in Week 1, he did not encourage it. “If I thought not playing Week 1 would make a major change, I’d give these boys the whole week off,” says Lynn. “I wouldn’t show up. But we’re football players, we’re not politicians.”

Still, don’t expect silence. In the past, Lynn says he’s tried to keep talk of controversial social issues—like Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the National Anthem—out of the locker room, lest it become a dreaded “distraction.” “We can talk about that s–t in February, in late February hopefully,” says Lynn, explaining his prior philosophy. Not so this year. “If I was to suppress this, I think it would hurt their passion and I don’t think they would play the game that they love well,” he says.

After Los Angeles made the playoffs in 2018, his second season as Chargers coach, Lynn’s team finished 5-11 last year. He’s under pressure to correct the course as the Chargers move into a new home. Lynn’s team will share SoFi Stadium with the Los Angeles Rams while desperately fighting for fans in an L.A. market that has greeted them mostly with indifference since moving from San Diego in 2017. Still, Lynn says his focus is not just victory on the field. “We have committed to winning the championship,” he says, “and fighting for social justice.”

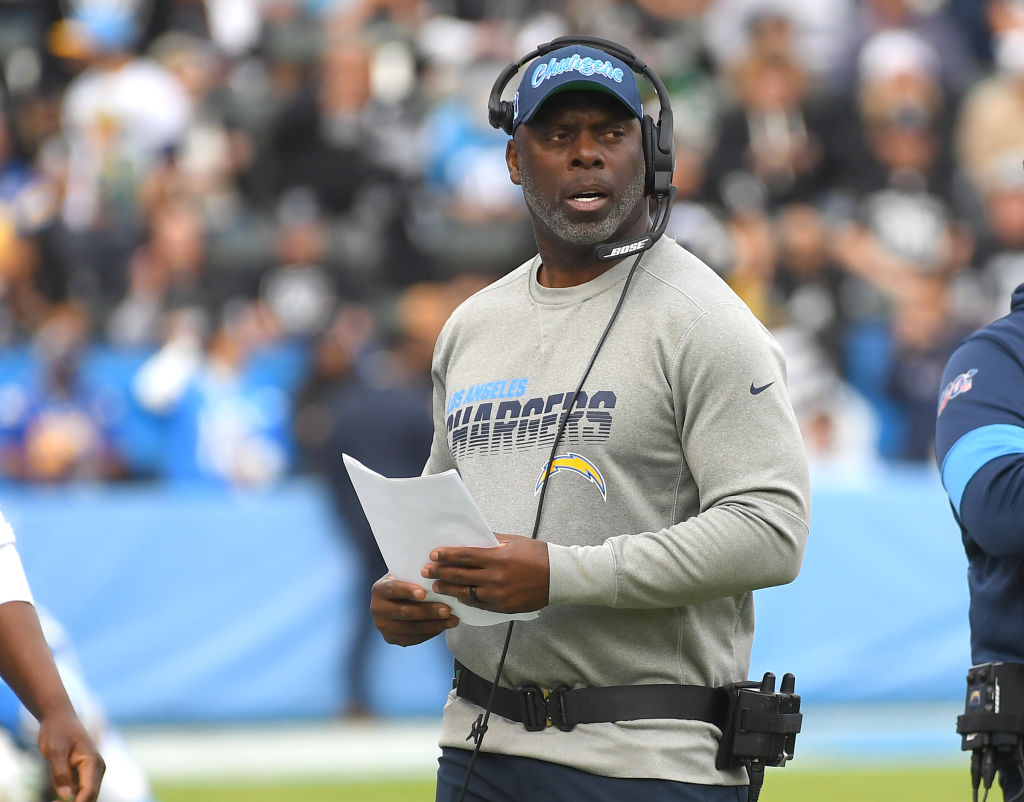

A bunch of plays are diagrammed on a white board behind his Lynn’s desk; he’s wearing a Chargers cap and jacket during our interview, and some gray stubble is peppered on his chin. Lynn’s no typically programmed football coach. He talks in a real, conversational manner, which is all-too-rare in his ranks.

As a kid he played quarterback on youth teams in football-crazed Celina. In seventh grade, however, a coach informed Lynn he’d be moving to running back. “He goes, ‘Black kids can’t play quarterback,'” Lynn says. Lynn asked why. “Well, they’re not smart enough,” the coach responded.

These accumulated experiences with racism “made me more aggressive,” says Lynn; he got into fights in school, but he also channelled his anger onto the football field, eventually earning a scholarship to Texas Tech University and playing in the NFL for the San Francisco 49ers and Denver Broncos; he won a pair of Super Bowl rings with Denver in 1997 and 1998.

Tensions boiled over during Lynn’s senior year at Texas Tech. Lynn says police were gathered at an apartment building where two teammates were staying; when he went to see what was happening, the cops “just jacked me up against a wall.” They asked if he was a drug dealer. “And I just lost it, man,” Lynn says. “The next thing I know I’m fighting with his cop and I’m on top of him and I get hit in the back of the head with a billy club and they got me tied down on the ground and they’re taking me to jail and the one officer kicked me inside my head.” Thanks to Lynn’s football connections, the cops eventually let him go. “Today, I would have been shot,” says Lynn. “I mean, think about that. I said, ‘I would have been shot.’ I was dead wrong going off on that cop. But it was just years of accumulation of this and that. I can’t go to the birthday party. I can’t play quarterback.”

Lynn stresses that he has great respect for police officers. In 2005, after he was struck by a drunk driver while crossing the street in Ventura, Calif., police officers helped save his life. The near-fatal incident left Lynn with temporary paralysis and injuries that required four surgeries. He has remained friends with one of the officers who rescued him. Still, he tires of the constant stings of racism. Just last year, he was pulled over for what he calls a “bogus reason.” Before a white officer asked him for license and registration, Lynn says, he asked if he had been in jail or on probation. “I’m afraid for some people that might not be as strong minded, if they hear something like that too many times, they start to believe it,” says Lynn. “That they’re not better. That they’re not equal. That’s my biggest fear. But for me, it just pisses me off. It always has.”

READ MORE: America’s Athletes Are Finally in a Position to Demand Real Change. And They Know It.

Lynn’s also irked that only three of the NFL’s 32 head coaches—Lynn, Brian Flores of the Miami Dolphins, and Pittsburgh’s Mike Tomlin—are Black. “I’m not comfortable with that number,” Lynn says. As recently as 2017, there were seven Black head coaches in the league. (Washington Football Team coach Ron Rivera, who’s Latino, is the NFL’s only other minority head coach). The Rooney Rule, which was implemented in 2003 to guarantee that at least one minority candidate is interviewed for open head coaching positions, seems broken. Is this the product of systemic racism? Lynn agrees that’s a fair assessment. “I played in this league for eight years, and a player knows a head coach when he sees one,” says Lynn. “There were African-American coaches that could have been head coaches but just never got the opportunity.”

How do you fix this? Lynn believes reforming the head coach feeder system will help. Between 2009 and 2019, according to a recent study from Arizona State University, offensive coordinator was the most frequent former position for head coaches: 40% of NFL head coaches were hired from offensive coordinator spots (NFL defensive coordinator, and NFL head coach, were the next most frequent positions). During same period, however, 91% of offensive coordinator hires were white.

“I’ve seen so many play callers get head jobs that have no personality, no leadership whatsoever,” says Lynn, who during his 17 years as an assistant coach in the NFL never entered a season holding a coordinator position (a few weeks into the 2016 season he was named offensive coordinator in Buffalo; that year he took over as interim head coach for one game after Rex Ryan was fired). His coaching career previously saw him as mostly a running backs coach and assistant head coach. Broadening the feeder system would result in a more diverse—and talented—candidate pool. “And then you wonder why every year in the National Football League we are firing anywhere from six to eight head coaches?” says Lynn. “If we open this thing up to position coaches, assistant head coaches, then you’re going to have more African-American applicants.”

He also believes Black coaches have to win faster than their white counterparts to keep their jobs secure. “I’m not happy with the leash that African-American coaches get,” says Lynn. “I had my first losing season last year. And I come home one day and my wife is like, ‘Honey, are you okay?’ And I’m like, ‘Why wouldn’t I be? I’m fine’. And she’s like, ‘Well, do you not know half the country wants you fired?’

When he entered coaching, Lynn understood the hurdles. The memories of being told he couldn’t attend a birthday party because he’s Black, or being asked if he was a drug dealer, were never too far from his mind. Lynn’s grandfather once told him he’d always have to be better because of his skin color. He’s never forgotten those words. “It’s a shame, but I know that going into it,” says Lynn. “I know I’ve got to turn this damn thing around, soon. But at the same time, I’m going to stand up for what’s right. I’m going to speak out when I have to. I’m not going to let that scare me from doing that as a human being.”

To wit: he’s unafraid to say that Kaepernick got a raw deal. Lynn is happy with this current quarterbacks, but did express some interest in Kaepernick earlier in the summer. “I do think there’s a possibility that Kaep could come on somebody’s roster this year because you can hold roster spots for veteran players now because of injuries and because maybe of COVID,” says Lynn. “There’s still a possibility there. But Colin’s busy doing things to help make a change and he’s signing big deals, he might not have the time to come back and play NFL football. But I know over the years he should have been given an opportunity. There’s no doubt about that. We’ve had those discussions. I can say that. We’ve had those discussions.”

Lynn is facing unprecedented challenges in carrying out his team’s turnaround plan. Start with his own bout with COVID-19; he was diagnosed while on a trip to Dallas, to visit his mother, in late June. “You always say, well, it’s really only killing 1%,” says Lynn. “But when you get it, start thinking about that 1%.” He’s not sure how he got infected. “I mean no one was more paranoid about this than me,” Lynn says. “You’re talking about a guy that has hand sanitizer in his front belt loop everywhere he goes. Wears gloves, masks.” Lynn’s lungs collapsed during the car accident 15 years go, which he feared would make him even more vulnerable. “And so it was some anxiety there for a little while,” says Lynn. “For me it was a really, really bad flu for about three or four days.”

In training camp, Lynn believes COVID-19 has affected team chemistry. “A big part of football is camaraderie,” he says. “When you have to social distance, it’s hard to build a team.” The first full in-person, locker room team meeting Lynn had was on Aug. 27, at SoFi Stadium, to discuss the Blake shooting. “I could just feel the people craving that community, that fellowship,” he says. “We haven’t had it. It’s going to be difficult to build tight teams and trust with new players when you don’t have that. The longer we do without it, the more of us see it. I mean, this is Zoom all year. Are you kidding me? It’s going to be different. But we knew that it was going to be a challenge and we’ve got to figure out a way to still make it work.”

The Chargers enter this season with veteran Tyrod Taylor starting at quarterback. A potential franchise QB, Justin Herbert—the sixth overall pick in this year’s draft, out of Oregon—will be the backup. (Quarterback Philip Rivers, who started every game for the Chargers the last 14 seasons, signed with Indianapolis in the offseason). Preseason games were cancelled this year; in some ways, this made Lynn’s training camp smoother. Because if Herbert shined in preseason games, screams to start him right away would have been pronounced.

In sticking with Taylor as the starter, Lynn cites John Elway and Peyton Manning, two legends who started their rookie years; each threw more interceptions than TDs (Manning threw a rookie-record 28 interceptions in 1998, tops in the NFL that year). “But those guys are two real strong-minded individuals, Hall of Famers,” he says. “Not everybody’s wired that way, man. It’s not everybody that can overcome that. So I don’t expect [Herbert] to come in and play right away. I think sitting him for a year would do nothing but benefit him.”

Does Herbert seem to have the Elway-Manning mentality, or is it too early to tell? “He is a leader in his own way,” says Lynn. “He’s more of an introvert. He quieter, but he communicates when he has to with his teammates. And people try to say that was a knock with him coming out. Said he has all the tools but wasn’t much of a leader. Introverts get labeled that way. I just know these players react well to him.”

The Chargers spent the last three seasons playing in a Carson, Calif. soccer stadium that held just 27,000 fans, by far the smallest capacity in the NFL. Now, they will move into a shiny $5 billion palace playing in front of zero fans, due to the pandemic, making the team’s effort to win the hearts and minds of Los Angeles even more difficult. “L.A. is a hard city,” says Lynn. “You have to be successful here, bro. You’ve got to win. And if you don’t, people just do other things. And there are other sports franchises here that people are attached to. So it’s no doubt a hard market. But people respect that hard work, young men of high character that are helping their communities and doing things that we’re doing. It’s just a matter of time before we have a strong fan base here. But we knew when we moved here it wasn’t going to happen overnight. Just like social justice. It isn’t going to happen overnight.”

More than ever, social justice will be a major theme of the NFL season. An Alicia Keys rendition of “Lift Every Voice And Sing,” a song known as the Black National Anthem, was played before Thursday night’s season-opening Kansas City Chiefs-Houston Texans game. At least some players are likely to kneel during the National Anthem or utilize some other form of protest when the NFL kicks off this weekend. Lynn recalls the reaction of his players after Blake’s shooting. “I’ve been dealing with this s—t since since I was nine years old,” says Lynn. “I was more sad that day for how they felt. We’ve got to move beyond it. We’re certainly not going to forget about it. But I wish I could do something to make them feel better in moments like that.”

Still, the Chargers coach remains confident that his recent powerful wave of sports activism will bring change, both inside and outside the NFL. “I’ve got to tell you, I’ve never seen so many people from all different backgrounds and colors come together and want change,” says Lynn. “So man, I’m hopeful. I’m very hopeful.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com