Immigration Nation, heralded by TIME’s TV critic Judy Berman as the “most important show” of 2020, presents a revelatory look at the inner workings of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers as well as the plight of many individuals caught in the web of contradictions that makes up the United States’ immigration system.

The six-part docuseries, arriving on Netflix Aug. 3, is a harrowing reminder that ever-changing immigration policies in the U.S. often leave entire families adrift—emotionally and physically. By following the stories of immigrants from all over the world trying to build their lives in the U.S., and embedding with ICE agents as they enforce immigration policies, filmmakers Christina Clusiau and Shaul Schwarz offer look at a system that is typically obscured from public view.

As an agency, ICE’s priorities have shifted since President Donald Trump took office in 2017 and brought in a hard-line agenda on immigration. Although the organization purported to only go after and deport immigrants who had committed serious crimes, the footage compiled by Clusiau and Schwarz shows moments when officers are encouraged to detain as many immigrants as they can, no matter what, amid many other shocking and potentially illegal actions, including parts when ICE agents improperly identify themselves as “police” and mislead immigrants about what rights they have. The filmmakers spoke to TIME to break down the process of filming some of the most powerful and often harrowing moments from the series.

Demands to arrest “collaterals”

A scene early on in Immigration Nation sets the surprising bar for how much ICE agents will go on to reveal on camera about the realities of their jobs. As the filmmakers are listening, a supervisor tells an officer over speakerphone, “Start taking collaterals, man. I don’t care what you do, but bring in at least two people.”

ICE agents are then shown arresting two “collaterals”—a term the agency uses to refer to the arrest of undocumented immigrants who are not their intended targets, have often not committed any crimes and are typically caught unaware. According to the filmmakers, that moment embodied ICE’s ethos and showed that the agency’s true mission often departs from what it publicly claims to do—arrest undocumented immigrants who are wanted for crimes.

“That happens all the time,” Schwarz tells TIME of the orders he heard over speakerphone. “It’s the reality of day-to-day in ICE. It wasn’t an isolated moment. Once the boots on the ground felt comfortable speaking with us, we got a very real peek into what it was like.”

Clusiau added that ICE agents, who currently work to fulfill the Trump Administration’s immigration goals, don’t mean to be “divisive or polarizing” by making such comments about immigrants who become unintended targets.

“It’s just part of the nature of what they do on a daily basis,” she says.

Moments where ICE and Border Patrol agents speak off the cuff are peppered throughout the series, and the filmmakers typically let those scenes speak for themselves. (The New York Times recently reported that the Trump administration sought to prevent the series from being released before the 2020 presidential election.) The candid moments illustrate the often highly contradictory nature of the officers’ jobs. In a particularly heartbreaking scene toward the end of the series, an agent with the Border Patrol’s Search, Trauma and Rescue Unit (BORSTAR) gives medical help to a migrant he comes across in the desert near Tucson, Ariz., who is dehydrated and suffering from several injuries. Although the agent is gentle in his care for the man, after he’s done, he tells a coworker how much fun he has aiding Border Patrol with apprehensions of immigrants.

“That moment was so interesting, to see them switch hats like that,” Schwarz says. “You saw kindness and humanity, but for Border Patrol, their job is to catch people. As the ambulance is leaving, they’re chit-chatting among themselves about how they chase people all the time.”

The detainment of one immigrant unravels the lives of many

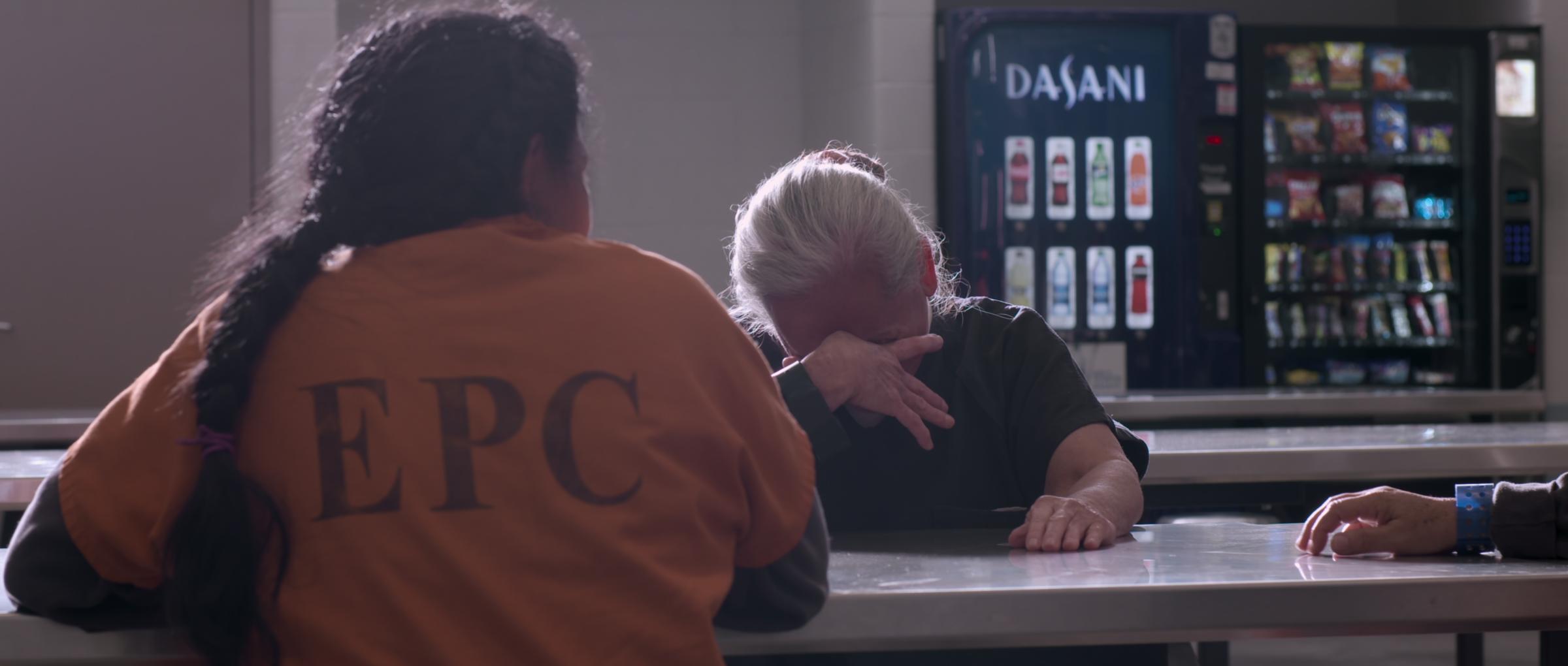

At the heart of Immigration Nation are the stories shared by immigrants caught within a draconian system, where constantly shifting policies often make little sense to the individuals most affected by them. We meet a father (pictured above with his son), handcuffed and in chains, who cries when he talks about how ICE separated him from his 3-year-old boy. We see an elderly woman deported after being detained by ICE for more than a year, following her attempt to seek asylum in the U.S. after MS-13 tried to forcibly marry her granddaughter.

One story that unfolds over the course of the series is that of a man named Bernardo, an immigrant from Guatemala who remained separated from his son when they came to U.S. even after the Trump Administration ended its family separation policy. While Bernardo stayed in detention, his son, Emilio, was released to his aunt, an undocumented immigrant living in the U.S. Trapped for months without being able to see his family, Bernardo’s plight causes pain for many people. Emilio struggles to fit in and feels burdensome to his aunt, who is taking on extra pressure by looking after him. We see Bernardo’s wife, Rebecca, who has stayed behind in Guatemala with their other children, go from frustrated to despondent over the situation.

“If I had known they were going to separate me from my son, I never would have left my country because it hurts a lot,” Bernardo tells the filmmakers through tears when he first meets them. “Even the best man cries about being separated from his child because we have a heart and we love our family.”

Bernardo’s story stood out to the filmmakers as an example of how “people get really chewed up by a random, unforgiving system.”

“Being in detention, not knowing what’s going on on the outside, not having resources to fight your case from the inside—it wears you down,” Clusiau says. “At times, he wanted to give up. But he didn’t. He kept going.”

The immeasurable psychological toll of limbo

As the series reveals, moving between detention centers and people’s homes across the country, individuals often feel the most pain while stuck in a waiting game initiated by ICE and immigration authorities, sometimes purposefully. Although the Trump Administration previously denied that its harsh approach in arresting immigrants and separating parents from their children was part of an effort to deter others from migrating to the U.S., at least one ICE agent brags on camera that taking children from their parents will be a good deterrent.

“A lot of these policies and these laws are inherently unfavorable or they are designed to be that way to install fear and to make people go more into the shadow,” Clusiau says.

And although their fates are mostly out of their hands, immigrants trapped within the system often blame themselves for their situations. Clusiau recalls speaking with Emilio, Bernardo’s son who was released to live with his aunt: “He thought it was his fault that he and his father were separated. I just remember thinking, that’s such a heavy thing for a 14-year-old to bear. Thinking that this was his fault, when we know in reality that is not true.”

Another story is that of a woman named Deborah, a refugee from Uganda, who lawfully applied for permission to bring her children to the U.S. in a case that remained stuck for years before they were allowed to join her—in part due to a push from the Trump Administration to reduce refugee resettlement in the U.S.

“With my case, they promise me that I’ll be able to have my children within a year, or even less, but they’re not here with me,” Deborah says as she continues her wait.

Clusiau reiterates that in the more than five years it took for Deborah’s children to be brought to the U.S., they did not have a mother present. “It was all stuck in administrative processing,” she says. “In the meantime, her children are growing up.”

Once in the U.S., immigrants are exploited for labor

Another episode of Immigration Nation shows how issues of immigration intersect with the workforce. After picking up on a pattern of immigrants moving to cities affected by natural disasters to find work, the filmmakers traveled to Panama City, Fl. in the months after Hurricane Michael in 2018, where several migrant workers landed to help rebuild the battered city.

“I just don’t think our workforce was here to handle it. We needed help. All I can say is I’ve been seeing a lot of Mexicans,” Don Ifero, a Panama City resident, tells the filmmakers. “Whether or not they’re legal, illegal, as long as they give me a quality of work, they gotta live, too. I welcome them.”

While the migrant workers’ residential statuses did not bother Ifero and other residents who needed their homes repaired after the hurricane, their ambiguous legal standing in the U.S. opened the door for contracting companies to take advantage of the workers, the series shows. The filmmakers followed a group called Resilience Force, which organizes for immigrant labor rights and helps migrant workers demand withheld pay. In Panama City, a firm called Winterfell Construction, owned by Bay County commissioner Tommy Hamm, was accused of paying no money to the several undocumented immigrant workers it hired to repair homes after Hurricane Michael.

Resilience Force organized Winterfell Construction workers and, in a dramatic scene, gathers several migrant laborers together to attempt to confront Hamm at his home to demand the payment of thousands of dollars. (Hamm told the filmmakers that none of the workers were directly in his employ and that subcontractors were actually responsible for paying the workers). While Hamm does not answer the door on camera, the mobilization of the migrant workers shows the power of their solidarity.

“They went down there, they didn’t know anybody, and by the end, a lot of them felt empowered,” Clusiau says. “It was fascinating to watch them organize.”

The power of grassroots organizing

ICE agents maintain that they are simply carrying out orders coming from the top. As the series shows, organizers working against an administration handing down these laws can feel like an uphill battle with no end. But grassroots organizers focusing on how they can make the lives of immigrants easier in their own communities are able to find local success.

The series introduces viewers to Stefania Arteaga, an immigration rights organizer who came to the U.S. as a child from El Salvador, who routinely puts herself in danger to advocate for immigrant rights in the Charlotte, N.C. area. Specifically, Arteaga is shown fighting against ICE’s 287(g) program, which allows the Department of Homeland Security to team up with state or local law enforcement agencies and allow them to do the work of federal agents, and its implementation in the Charlotte area. She lobbies for the election of a new county sheriff who has promised to end the program.

The filmmakers follow Arteaga as she confronts police on several occasions. Filming on her phone, she asks clear questions as officers are trying to detain immigrants. “What type of operation is this? You’re undercover so we’re just trying to make sure we know who is on our streets,” she says to one officer as he tries to avoid her.

“Stefania, she is a force,” Clusiau says. “She realized the 287(g) program was something they could really push back against, and they did. They had an issue they could really stand behind.”

In one chilling encounter, Arteaga broadcasts live from a scene where officers from an unmarked vehicle are trying to detain multiple immigrants. They refuse to answer her questions. As the van pulls away, Arteaga tells the camera, “I’m a little shook. I’ll be honest, I was really scared right there. You never know.”

Arteaga’s efforts paid off—following his swearing-in in 2018, Mecklenburg County Sheriff Garry McFadden sent a letter to ICE to stop the county’s participation in the 287(g) program.

“For immigration advocates, these last couple years have been tremendously hard,” Schwarz says. “When you spend so much time in this broken system, you tend to lose hope. But she embodied something that’s amazing about democracy. She created this pushback and put herself in the middle of it. There’s something to be said about it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com