When someone says no one cares about Black women and girls, I tend to reply, “we all we got.” It’s a slight correction to a sentiment that’s understandable. There is, after all, ample evidence that much of the world does not have much concern for the well-being of Black women, girls and femmes, but to say that no one cares fails to acknowledge those who do, those who work to protect and support them. As Christina Sharpe, the inimitable author of In The Wake: On Blackness and Being, reminded me a few weeks ago: Black women, girls and femmes have always looked out for each other.

In the past, I admit, I too asserted without qualification that no one cares about us, overlooking historical and contemporary examples of Black women and femmes showing up for and centering the plight of Black women, girls and femmes. Even as a Black feminist, I participated in the racist and sexist practice of erasing Black women’s labor. I said no one cared because I was angry that far too few people beyond other Black women and femmes care about our victimization or the energy we expend struggling against injustice.

Today the undervaluing of the labor and commitment of those of us who do care and show up for Black girls, women and femmes looms large. Black women and femmes keep developing radical ideas about social transformation, wrestling with the ways anti-Blackness manifests in areas such as the criminal justice system, health care, news media and popular culture, and tirelessly amplifying the experiences of Black women, girls and femmes. But even as our ideas are coopted, our victimization remains on the margins.

Our limited visibility as prominent architects of the burgeoning 2020 uprising and as victims of racial injustice feels all too familiar and has left me with disconcerting questions: What will it take for folks to not use our ideas and strategies without crediting us or centering injustices against us? Should Black women, girls and femmes give up on expecting anyone other than us to care? Is solidarity even a meaningful goal if folks continuously fail to cite our labor and center our marginalization?

The problem we endure is one of constant erasure. For example, the origins of anti-rape activism in the U.S., although largely attributed to feminist activists in the 1970s, date back more than 150 years. In 1866, a group of African-American women testified before Congress about being gang-raped by white men during the Memphis Riot. Despite compelling testimony, the perpetrators were not punished. After this pioneering moment in anti-rape activism, African-American women such as Fannie Barrier Williams and Ida B. Wells founded and participated in campaigns to end sexual violence against Black women and girls. Black women in the late 19th century laid the groundwork for future generations of anti-rape activists. In the 1970s, which many consider the “third peak” in anti-rape activism, the strategies and aims of Black women’s anti-rape activism became part of a broader movement that included the creation of rape crisis centers and college campus activism.

Many of the trailblazing African-American women who documented, analyzed and fought against sexual violence, however, became mere footnotes in the historical record of the enduring struggle to end sexual violence. This made it easier for folks in 2017 to overlook Tarana Burke, who founded the #MeToo movement in 2006, and to not identify Aishah Shahidah Simmons’ NO! The Rape Documentary as a germinal film about contemporary sexual violence. It was also unsurprising that the stories of primarily famous white women took centerstage in national debates. Black women’s work anchors anti-rape activism, and yet sexual violence against Black women, girls and femmes remains under-addressed within the mainstream anti-rape movement.

History appears to be repeating itself as calls to #DefundThePolice intensify. This part of the current racial justice movement owes a tremendous debt to the grassroots organizing and scholarship of Black feminists and other feminists of color over the past few decades. From Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera and the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries who knew they could not look to police or prisons to address violence against queer and trans people to Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Angela Davis and others forming Critical Resistance as a grassroots organization striving to dismantle the prison-industrial complex, the demand to abolish policing and prisons is hardly new. Davis argued in her 2003 book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, that“the most difficult and urgent challenge today is that of creatively exploring new terrains of justice, where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.” Defunding the police is a means by which abolition becomes possible.

While more folks are now engaging the work of Black women like Davis, Gilmore and other Black feminist abolitionists on policing and prison abolition, some people are missing key Black feminist sensibilities that undergird demands to radically transform the criminal justice system. Systems of policing currently allow people, from police officers to intimate partners, to harm Black women, girls and femmes with no accountability. The move to divest from policing and prisons demands an understanding of interlocking systems of power in which Black women, girls and femmes are disproportionately vulnerable to violence and to being overpoliced.

The call to defund and ultimately abolish police is predicated upon examining the conditions in which harm thrives. It also compels us to care about, prevent and address harm outside of a punitive context through investment in areas like education, health, housing and employment, areas in which Black women, femmes and girls combat notable bias, disparities and inequities.

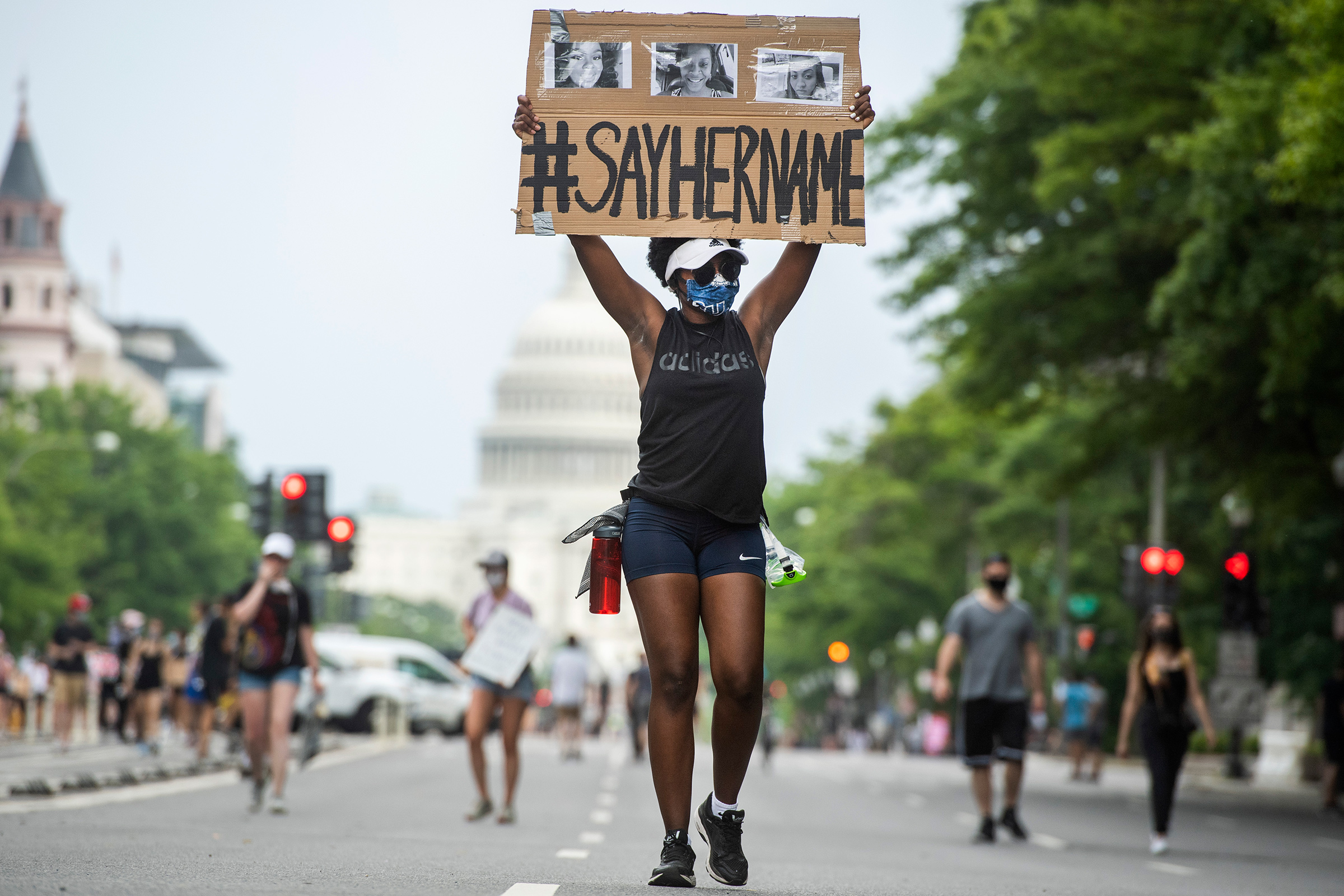

To re-center the lives and labor of Black women, girls and femmes in the current debate about #DefundThePolice isn’t merely about recognition; it’s about ensuring that we don’t render them as “no one.” In 2014, Black women created #SayHerName to push people to acknowledge that Black men are not the only ones killed by police at a disproportionate rate. While there were massive protests after the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner, we did not see similar public outrage over Rekia Boyd, Tanisha Anderson or other Black women, girls and femmes who died at the hands of police. “Although Black women are routinely killed, raped and beaten by the police, their experiences are rarely foregrounded in popular understandings of police brutality,” said Kimberlé Crenshaw, who authored and published the #SayHerName report with Andrea Ritchie, and the African American Policy Forum in 2015. “Yet, inclusion of black women’s experiences in social movements, media narratives, and policy demands around policing and police brutality is critical to effectively combating racialized state violence for black communities and other communities of color.”

Today these deaths still don’t get the nearly the attention or mobilization our male counterparts do. It took George Floyd’s death for people outside of Louisville to march for justice for Breonna Taylor, who was killed by police two months earlier. And beyond Black trans and non-binary people and a few non-trans allies, I suspect few people even know about the killing of Brayla Stone, a 17-year-old Black trans girl whose body was found in June, or the five other Black trans women who were killed between June 25 and July 3.

I don’t know how to convince people to care about the lives of Black women, femmes and girls like Taylor and Stone, but I do know that they’re not “no one” and neither are the Black women and femmes fighting for them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com