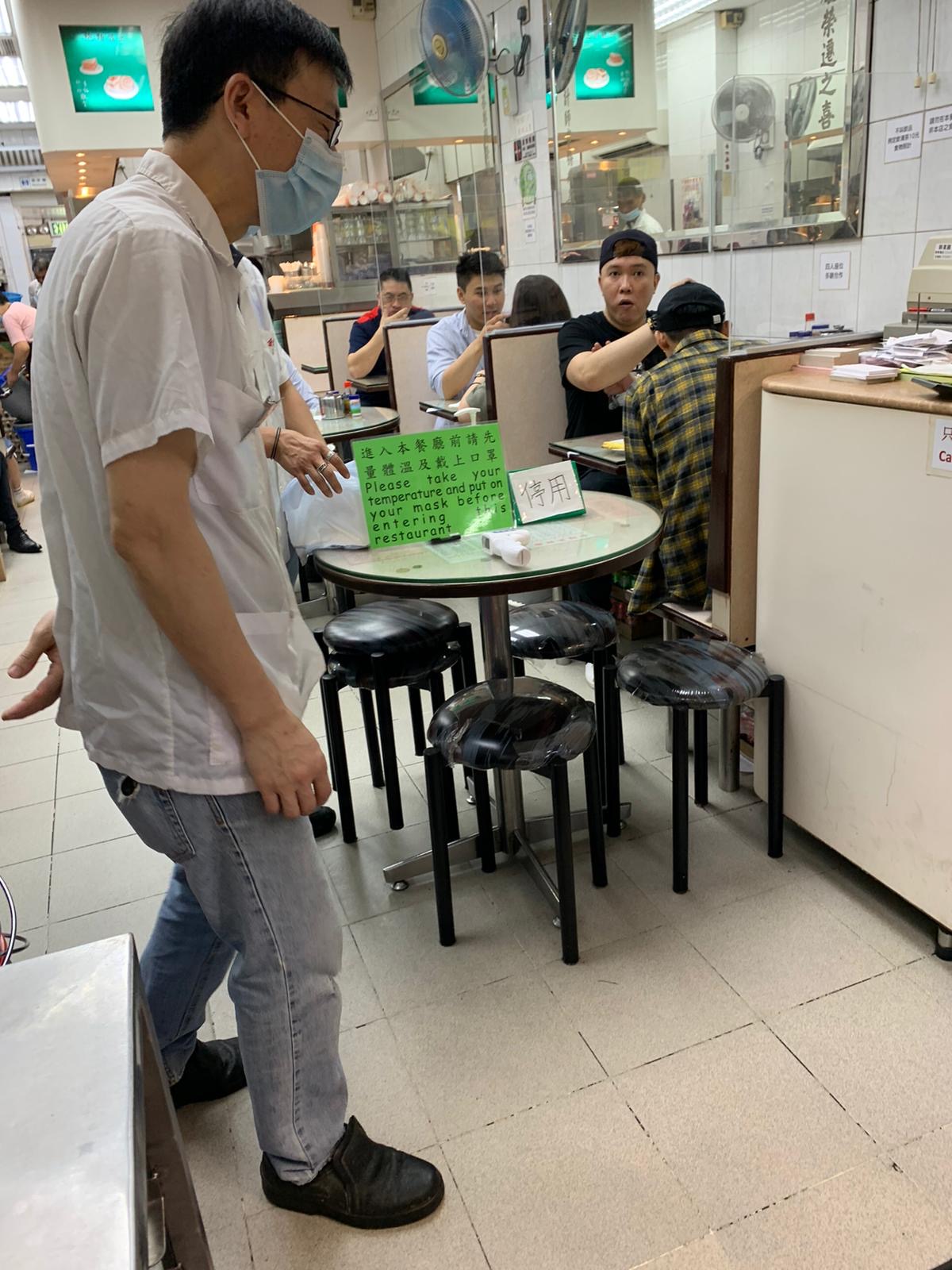

A large sign sits in the front window of Kam Fung Cafe, a tiny local diner on a narrow side street in Hong Kong’s bustling Wan Chai district: “Please take your temperature and put on your mask before entering this restaurant.”

Tall clear plexiglass sheets have been installed atop the small booths lining two walls of the restaurant. The front table, one of only three or four in the compact cafe, has been sacrificed to create a temperature-taking station. Ms. Ho, one of the restaurant’s workers, tells TIME that since the coronavirus pandemic, they no longer seat strangers together at a booth, a common practice at space-constrained local Hong Kong restaurants.

In Hong Kong, a city known for its vibrant culinary scene, restaurants are once again buzzing with diners now that coronavirus appears to be under control here. But nearly every eatery—from the smallest cafes to Michelin-star restaurants—have implemented safety measures to protect diners from the coronavirus.

The measures appear to be working. Hong Kong hasn’t recorded a cluster of coronavirus cases related to restaurants since the safety measures were put in place in late March. That may provide a model of how to operate under a new normal for restaurants in places like the U.S. and Europe, where many businesses are just starting to open up again.

The trajectory of the coronavirus in Hong Kong demonstrates the need for precautions when it comes to dining. One of the first large clusters in the city was linked to a late January family gathering at a hot pot restaurant—where diners share a communal cauldron in the center of a round table, fishing meat and vegetable morsels out of broth with chopsticks or spoons. At least 13 cases in the city were linked to that hotpot meal.

Hong Kong has avoided the strict lockdowns seen in the U.S. and Europe, but it has had various social distancing measures in place since January when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported. Restaurants have remained open throughout the pandemic—albeit with reduced capacity and restrictions on group size. COVID-19 case numbers in the city have dwindled, and restaurants are now allowed to operate at full capacity with groups of up to eight people allowed to dine together. Restaurants are required to space tables about five feet apart, or to place a partition between them. Customers, who are asked to wear masks except when eating or drinking, are provided with hand sanitizer. And restaurant staff are required to take patrons’ temperatures before they’re allowed to dine.

Some restaurants are getting creative with the rules. A restaurant in K11 mall in the city’s bustling Tsim Sha Tsui district is using large images of artwork by famous artists like Monet to separate tables.

Some restaurants are implementing more stringent precautions. At Associazione Chianti, a Tuscan steakhouse in Wan Chai, restaurant staff have lined the narrow sidewalk outside with large red dots, spaced about 5 feet apart, to indicate where guests should stand as they wait to be seated. Customers must sign health declaration forms saying that they haven’t traveled outside of the city in the last 14 days—anyone who returns to the city is required to quarantine for that length of time. Atop the red and white checked table-cloth of every table sits hand sanitizer, alcohol wipes and an envelope for holding diners’ face masks while they eat.

Tony Ferreira, director of culinary operations for Black Sheep Restaurants, which runs Associazione Chianti, tells TIME that they’ve taken some less obvious precautions too, like training front of house staff to escort people to their tables as quickly as safely possible to avoid crowd congestion in the small reception area.

Black Sheep, a restaurant group with 25 restaurants across the city, has published a “COVID-19 playbook” that makes public its strategy for protecting its guests and staff from the coronavirus. According to the guide, physical contact like high fives and handshakes have been banned in the group’s restaurants and staff are required to wear masks and wash their hands every 30 minutes.

As in Hong Kong, restaurants across the Asia-Pacific are reopening cautiously. In Australia, several states are allowing restaurants and cafes to open for in-house dining, but only 10 diners are allowed inside at a time. One restaurant in the Australian state of New South Wales, has put cardboard cutouts of human diners where real humans aren’t allowed to sit. Frank Angilletta, one of the restaurant’s owners tells TIME that it started out as a joke, but it helps to separate people. “It adds a little atmosphere, some normality,” he says. “[Customers] say they didn’t feel like they were the only table in there.”

In some cities in mainland China, customers can only enter if a health-tracking app many Chinese are required to use shows that their health status is “green.” In Taiwan, restaurants are required to maintain a distance of about five feet between diners. A cafe in Bangkok, Thailand is serving coffee in a box on wheels via a pulley system to limit contact between its baristas and customers.

How have restaurant customers reacted?

Restaurateurs say the reaction to the safety measures has been mixed. In Hong Kong—where emotional scars from the 2002 to 2003 SARS outbreak have ingrained hygiene precautions as habit—people adopted some safety measures quickly. Mask wearing in all public places became de rigeur by late January.

Ferreira of Associazione Chianti says that when a guest calls for a reservation he or she is walked through the procedures the restaurant has in place. “So there are no surprises for them, no stress,” he says.

Syed Asim Hussain, co-founder of the Black Sheep Restaurants, tells TIME that at first, there was some pushback—especially against the customer health declaration form and temperature checks. (His restaurant group implemented many protections before they were mandated by the government.) On one night earlier this year, the group’s restaurants turned away more than 50 potential customers who didn’t want to comply.

“We had a zero compromise policy,” he says. “It was tough because we are in the business of looking after our guests. We are in the hospitality business.”

He says that customer attitudes have shifted, and many are now appreciative of the measures. But he adds, with plexiglass dividers and hand sanitizer bottles visible across his restaurants, it’s been more difficult to create the ambiance that Black Sheep restaurants are known for.

“I’m very romantic about our restaurants,” says Hussain. “I’m very careful about what our places aesthetically look like, but all of that has gone out the window.”

Deborah To, who is from Australia but has lived in Hong Kong for 10 years, tells TIME that she’s now used to the safety precautions that restaurants across the city have in place, but some things don’t feel quite the same. She says it was “super weird” when she and a group of friends went out to dinner to celebrate a friend’s birthday and had to sit at separate tables due to restrictions on the number of guests at one table.

Do guests feel safer?

Black Sheep says that the precautions they put in place have helped build trust with their customers and given them confidence to visit the group’s restaurants.”Seeing our team members wash their hands in front of them, using our sanitizer bottles to sanitize tables when we’re setting tables, these things really put peoples’ minds at ease,” says Ferreira.

And Hussain says the measures have guarded them against the disaster of having a cluster linked to their restaurants—none of Black Sheep’s staff or guests have been infected while working or dining at the restaurants, though two restaurants closed temporarily when patrons who later tested positive were found to have dined there. “I think these protocols have somehow, some way, protected us,” he says.

To, 32, who often eats at Black Sheep restaurants, says being forced to use hand sanitizer before a meal and seeing staff wearing masks makes her feel a lot safer.

Food blogger Kelvin Ho—whose Instagram account EpicurusHongKong has more than 46,000 followers—says he has become really picky about where he eats in recent weeks. He says if a restaurant doesn’t appear to be following the safety measures strictly, he won’t go—he’ll no longer eat at one chain he saw people entering without masks.

“I nitpick. If [the tables are] still relatively close together…I wont eat there. I tend to find places with higher ceilings,” he says. “I have walked away.”

Is it a viable model?

COVID-19 has hit the restaurant industry hard everywhere—including Hong Kong. Restaurant visits across the world were down more than 92% year-over-year from on May 19, according to data published by OpenTable.com, based on a sample of 20,000 restaurants it hosts on the platform.

Hussain says that there were a few nights earlier this year when not one customer came to one of the group’s restaurants in Hong Kong.

The new measures are hard on the bottom lines for Hong Kong’s restaurants—many of which were already reeling from six months of anti-government protests in 2019 that kept residents home and scared away tourists. Table spacing requirements can be particularly tough in Hong Kong where spaces are often small, and rents are some of the highest in the world.

“Physical distancing especially is difficult, that means you can’t run your restaurant at optimum revenue,” says Hussain.

But he says, given that coronavirus is likely going to be around until a vaccine can be developed and deployed, they’re making the best of a bad situation: “I think the choice is very clear, either we try to exist within this new framework, or we don’t exist. We’re trying to make the best of it. It’s going to be a tough year.”

Are restaurants forever changed?

Hussain says that he’s preparing to run his restaurants with at least some of the new measures for the long term.

“This notion of things returning to normal, that’s not going to happen,” he says.

Hong Kong food blogger Andrew Tang, 31, hopes some of the changes will be permanent. “I think hand sanitizer is a must, now we’re kind of used to it,” he says.

Ferreira of Associazione Chianti says that many of the changes are likely to stick: “Social distancing, sanitizing, alcohol wipes, it’s here to stay, I think it’s going to be part of the new norm.”

— With reporting by Aria Chen in Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Amy Gunia / Hong Kong at amy.gunia@time.com