“Tooth-deprived bigots.” “Globalist cucks.” “Jewboys.” “Crisis actors.” “Inbred rednecks.” “Godless elites.”

There’s no shortage of offensive language in The Hunt, a film that caused an uproar when its trailer was released last summer in the wake of two mass shootings. Fox News railed against it; social media exploded; then the President himself weighed in, saying the film would “inflame and cause chaos.” “They create their own violence, then try to blame others,” President Trump tweeted of “Liberal Hollywood.” A day later, Universal Pictures canned the film.

But seven months later, the action film has been put back on the schedule and will arrive in theaters March 13, during an uncompetitive stretch of the film calendar before the onset of summer blockbuster season. While the filmmakers are still trying to make sense of the strange turn of events, they say the movie was completely misunderstood—and the firestorm around it has only reinforced the critique at the heart of the film, of the country’s antagonistic, conspiracy-driven discourse.

“The fact that the film deals with misinformation—and then there was this misinformation that happened to the movie—it’s been a surreal experience, and has led us to a place where its relevance is even greater,” director Craig Zobel tells TIME.

“Crazy Conspiracy Theories”

The premise of The Hunt is, on its surface, undeniably incendiary. A group of men and women who are labeled as “deplorables” wake up in a field, gagged and handcuffed. They soon realize that they are being hunted for sport by a group of wealthy liberals, who use machine guns, grenades, giant spikes and arrows to kill them. But one of the captors, Crystal (GLOW’s Betty Gilpin), evades their traps and fights back, killing her predators one by one.

The idea initially arose as a half-joke from the screenwriters Damon Lindelof and Nick Cuse, who were in the midst of writing the critically-acclaimed, grief-soaked drama The Leftovers. “The Leftovers was all about a deep dive into magical thinking, and exploring belief as a coping mechanism for not understanding how the world works,” Lindelof, also a creator of Lost and Watchmen, says. “So we were constantly talking all the time about crazy conspiracy theories.”

One day, the pair was discussing Pizzagate—a debunked conspiracy theory that accused Hillary and Bill Clinton of running a pedophile ring out of a pizza restaurant basement—when Lindelof asked Cuse, “Is there anything we wouldn’t believe about the quote-on-quote other side, or that they wouldn’t believe about us? What’s the most ridiculous conspiracy theory that could possibly manifest?”

And so The Hunt was born. Lindelof and Cuse hoped to make a “Jason Blum movie”—referring to the producer behind action-horror-meets-social-satire films like Get Out and The Purge—while also conjuring the profane absurdism of Veep. “As a fan of Veep, it’s like, ‘oh, they’re making abortion jokes.’ But it’s not controversial, because the audience understands what the show is,” Lindelof says.

They got to work creating outrageous plot twists, gruesome gore and silly caricatures of both liberals and conservatives. They stacked the script with uproarious message board-style insults and decided that it would be funnier if the liberals were the hunters, “because we would be very bad at it,” Lindelof says. “We would be very conscientious about all the rules governing the hunt itself, and we would not have the skills to execute it, pun intended.”

The pair consulted with friends across the political aisle for feedback on their portrayal of right wingers. They also tapped Zobel, who had directed episodes of The Leftovers, to bring their idea to fruition. “I wanted to try to make a film I would want to see at the moment, which is not necessarily one that would lecture me,” Zobel says. “I wanted to see a movie that would help me laugh at myself.”

While Lindelof and Cuse skewered both sides with abandon, they realized the story needed a moral center who could unite audiences regardless of their political affiliation. So they created the protagonist, Crystal, a disaffected veteran from Mississippi who works for a car rental company and is thrust into the hunt accidentally. “The whole point of the character is that they’re projecting a certain belief system on her, based on where she’s from and what she may have says in a comment section,” Lindelof says. “If you identify as super right wing or super left wing but can agree Crystal is awesome, that is her purpose: to be the overlap in whatever Venn Diagram exists.”

The Calm Before the Storm

Lindelof and Cuse brought their script to Blum himself, who read it and immediately understood its tone and aims. “It felt very similar to The Purge, and equally outlandish,” Blum says. “The most important part was that it was a super fun action movie.”

Blum signed on through his own Blumhouse Productions and their venture with Universal Studios, and the movie rolled forward with a $15-million budget. Lindelof says that even with a major studio backing the project, he wasn’t asked to tone down any political aspects while making the film. “Nobody at any point in the process said, ‘this is controversial,’” he says. “We shot in New Orleans, and on the crew, there was an incredible blend of political ideologies. Everybody seemed amused by the movie.”

A release date was set for September. The first trailer, which portrayed the film as a straightforward horror flick in which “deplorables” are gunned down mercilessly, was released at the end of July. But that weekend, gunmen in El Paso and Dayton killed 31 people. The trailer’s caustic and homicidal tone suddenly rang inappropriate in a fraught moment; ESPN pulled an ad, and Universal Pictures paused its marketing campaign.

The following week, a test screening was shown in Los Angeles—and the Hollywood Reporter reported that audience members expressed discomfort with the film’s politics. But Blum, Zobel and Lindelof all denied this account. “The politics of the movie never came up at the test screening,” Blum says.

Lindelof remembers reading a couple responses from the focus groups that mentioned politics: “Some people wrote, ‘It was a little annoying when it was preachy,’” he says. “But I don’t recall someone ever writing that they were uncomfortable or put off by it.”

Lindelof also says that the focus groups were asked whether the film felt inappropriate given the recent mass shootings. “They seemed kind of confused by the question, and a couple of them got offended the question was even asked of them. They were like, ‘It’s a movie! Why would it be inappropriate?’” Lindelof recalled.

Blum says that he and Universal were reassured by the test screening feedback, and were about to move forward with the release as planned. Lindelof, after working on Watchmen for a year and half, headed to the Bahamas with his family for a vacation.

“A Sick, Twisted Movie”

Lindelof was hanging up his swimsuit on the second night of his vacation when his son came into his room and told him, ‘The President of the United States just tweeted about your movie.’”

“I said, ‘ha, ha,’” Lindelof recalled.

Unbeknownst to the filmmaker, a firestorm was erupting on right-wing websites and channels like Fox News, which had latched onto the trailer and were excoriating its treatment of Trump supporters. Fox Business host Lou Dobbs called it a “sick, twisted new movie,” adding that the idea of “globalist elites hunting deplorables sounds a little too real.” Trump tweeted a condemnation of the film, albeit without naming it directly, to his 73 million followers.

Executives and the filmmakers began receiving death threats on social media. Universal quickly pulled the film, with little resistance from any party. Blum says that “it got serious enough that I wanted to pull the movie.” Lindelof was not part of that decision-making, but was unsurprised: “As soon as I saw [Trump’s tweet], I thought, ‘this movie is not coming out,’” Lindelof says. “My naiveté was exposed by this entire scenario. I felt kind of dumb and sad.”

Ironically, the turn of events had mirrored the movie’s central point: that in this polarized climate, people jump to conclusions about others across the political aisle without regard to fact. In the film, the hunted conservatives make bold claims about the deep state and the immigrants ruining the country; meanwhile, the liberal hunters justify their actions by assuming their prey are racist bigots. The irate conservatives in real life had assumed the film was advocating its violence instead of critiquing it—and their campaign had led to the cancellation of a film that had actually hoped to bridge the political divide.

“When that happened, it proved the thesis of the film, in a way,” Zobel says.

Reframing Expectations

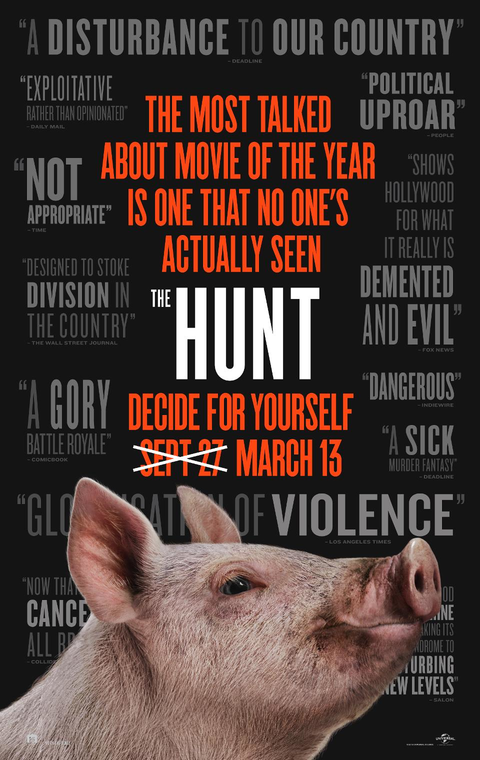

Seven months later, the movie is back on: the filmmakers say that time has dulled the furor from conservatives, as well as the narrative that tied the film to the two mass shootings. The actual film hasn’t been changed at all; instead, Universal has simply shifted the marketing campaign. A new trailer was released February, which paints the film as a tongue-in-cheek thriller and alludes to the controversy itself, with the villainous Athena telling Crystal: “You wanted it to be real, so you decided it was.” A new poster calls the film “the most talked about movie of the year that no one’s actually seen.”

“The game that needed to be played was reframing people’s expectations,” Lindelof says. Referring to the opening scene, in which a pretentious millionaire brags about expensive limited-edition champagne, he says, “You don’t cast Glenn Howerton [an actor who often plays villains] to be the first character in a movie, going on and on about bottles of champagne recovered from subs on the ocean floor, if you’re trying to be serious.”

Paul Dergarabedian, a senior analyst at Comscore, a media measurement company, praised the rebrand, and says that the controversy could actually benefit the film’s bottom line in the long run. “Usually, controversy helps, because it simply raises awareness for a film,” he tells TIME.

Dergarabedian expects the film to perform in the mid-teens of millions and to make back its $15 million budget in the first weekend; he also says it helps that the film was released in a muted stretch of the year (as opposed to the prestige film-driven winter or the blockbuster-driven summer) and on a weekend where the main competition is the kid-friendly Onward.

Blum has since rebounded with Blumhouse’s The Invisible Man, which was a surprise hit last weekend, making $30 million in its first four days. He’s relieved to be done with this controversy, but says that it will have lingering effects on Hollywood’s decision-making. “The way topics are tackled in films is oftentimes now less interesting because people are, in my mind, overly sensitive,” Blum says. “I think movies have to be compelling and exciting—and that’s hard to do in this climate.”

But Zobel says that after this long wait, the film has only become more timely. “We’re going into a period this fall where we’ll be in a torrent of media aimed at dividing us during this election season,” he says. “I hope people can laugh at how we divide ourselves into groups—there’s a lot to be laughed at in what’s happening right now.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com