In a historic rebuke, the House of Representatives formally impeached President Donald J. Trump on Wednesday evening on charges that he abused the power of his office for domestic political advantage and subsequently obstructed Congress’ abilities to hold him accountable.

The votes, which were almost entirely along party lines, rendered Trump the only first-term President to be impeached, and the third in the country’s 243-year history. House Democrats will now make their case in a Senate trial as to why Trump should be removed from office for linking congressionally approved foreign aid to Ukraine with an investigation into the family of former Vice President Joe Biden, a leading contender to face Trump next year as the Democratic Party’s nominee.

National security experts have condemned Trump’s actions and historians deemed them to be an abuse of power, but the principal outcome of the impeachment process so far seems to have been an intensification of the politicization of even the most serious constitutional matters. The House inquiry into Trump’s conduct brought high drama but little real suspense, as Trump’s impeachment, despite the contrary insistence of Democratic leaders, seemed pre-ordained since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi formally announced it in September. Republicans both inside and outside Congress rallied to the President’s defense, while Democrats stood by Pelosi and House Intelligence Committee chairman Adam Schiff, who became the faces of the probe. The process reinforced the political fault lines that have hardened during the first three years of the Trump administration. As the process now moves to the Senate, it seems inevitable these divisions will only intensify as the nation gears up for elections next year.

A split screen emerged during the vote that reflected the polarization that may deepen further as the 2020 race heats up. As lawmakers swarmed the front of the floor to cast their historic votes by hand — Democrats supporting the articles voted on green notecards, and Republicans opposing on red ones — Trump was on stage front of a screaming crowd at a Michigan rally. “By the way, it doesn’t really feel like we’re being impeached,” he told the crowd. “The country is doing better than ever before. We did nothing wrong. And we have tremendous support in the Republican Party.”

The fight now goes to the Senate, where a two-thirds majority is needed to remove Trump from office, or 67 lawmakers in a chamber currently divided among 53 Republicans, 45 Democrats and two independents who caucus with the Democrats.

But, like the House, the outcome once again seems pre-determined. For Trump to be removed from office, Democrats, should they stay united, need to peel off 20 Republicans, a nearly impossible task. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, whose mastery of the politics and the process of the Senate is unmatched, has said for weeks that he can’t fathom this scenario. Hopes that conduct in the Senate will be more bi-partisan are fading fast. McConnell has said he is working directly with White House Counsel Pat Cipollone, who is expected to lead some of the President’s defense during the trial. That open coordination drew condemnation from Democrats, but it simply reflects the reality of what is to come: Republican lawmakers are unlikely to turn on a President from their own party who has sky-high poll numbers among the base.

“Thats certainly an indication of an intention to have an unfair trial,” House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler said Wednesday evening.

Under current Senate rules, the Senate must immediately turn to the trial after the House vote, but a trial is unlikely to begin until Senators agree on its rules. Pelosi said as much Wednesday evening. “We have legislation approved by the Rules Committee that will enable us to decide how we will send over the articles of impeachment,” she told reporters Wednesday after the votes. “We cannot name [impeachment] managers until we see what the process is on the Senate side, and I would hope that would be soon.”

But lawmakers have already started jostling over the parameters of the looming battle. That negotiation has emerged as a kind of early litmus test on whether Democrats can muster any defections from across the aisle — or at least tuck away a few barbs they can use in next year’s political campaigns. Republicans have the numbers to dictate the rules of the trial, but Democrats have been trying to pressure the GOP into compromises to allow new documents and testimony to be presented.

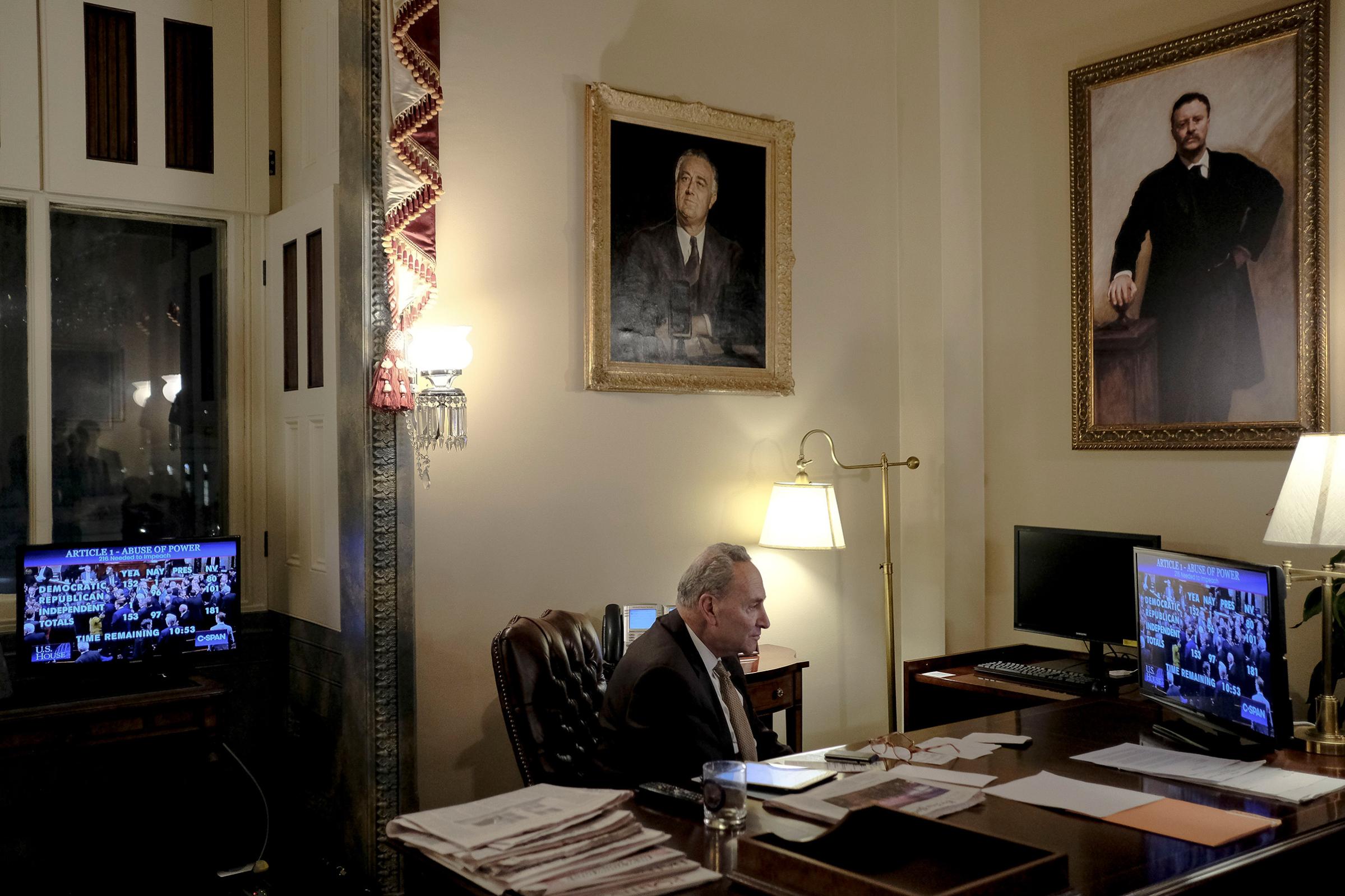

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has been trying to build a pressure campaign on Republicans who cast themselves as principled lawmakers like Susan Collins of Maine, Mitt Romney of Utah and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska to consider his subpoenas for new documents and testimony from members of Trump’s Administration that the House did not consider. In a letter over the weekend, Schumer outlined his ideas for how to structure the unfolding case. McConnell has dismissed the notion. “If House Democrats’ case is this deficient, this thin, the answer is not for the judge and jury to cure it over here in the Senate,” McConnell said in a fiery speech from the Senate floor on Tuesday. “The answer is that the House should not impeach on this basis in the first place.”

An agreement between Schumer and McConnell on the trial format looks elusive. As of Wednesday, the two weren’t yet scheduled to meet to hash it out, and both are telegraphing frustration in public remarks. Schumer says it was wrong for McConnell to tell a Fox News host before the trial that the President was going to survive the vote; McConnell says Schumer should have debated process and format in private, rather than a publicly released letter.

They do, however, have some common ground. Neither wants to see a Senate trial devolve into a dragged-out spectacle as an election year kicks off — a notion that Trump has suggested he’d be up for. “I’ll do long, or short. I’ve heard Mitch, I’ve heard Lindsey. I think they are very much in agreement on some concept,” Trump told reporters in the Oval Office on Dec. 12. “I’ll do whatever they want to do. It doesn’t matter.”

McConnell has been clear that he wants to get back to other Senate business as soon as possible, such as confirming a raft of judicial nominees. And Schumer must recognize that there is little political advantage to Democrats in prolonging the process after the format of the trial is established; if Collins, Romney and Murkowski won’t defy McConnell on the basic rules, there’s little chance Democrats can rally the Republican votes they’d need to remove Trump from office.

Given this vote’s proximity to a presidential election year, political calculations have inevitably hung over both parties’ arguments. Democrats claimed they had to push ahead with the investigation and vote because Trump has already tried to undermine the election, while Republicans said voters will finally have their say decide at the ballot box. It’s too early to guess the impact of the process; eleven months is a long time. But those voters will almost remember whose side they were on. And those results will speak for themselves.

With reporting by Tessa Berenson/Washington

Correction, Dec. 20

The original version of this story misstated the circumstances of President Donald Trump’s impeachment. He is the only elected first-term President to be impeached, not the only first-term President to be impeached.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com and Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com