Harry Belafonte, the singer, actor and activist who broke one barrier after another in his tireless fight for equality and civil rights, died on April 25. He was 96 and died of congestive heart failure, a spokesperson confirmed to TIME.

With knockout good looks and a warm, acrobatic voice, Belafonte rose to fame as a matinee idol in the 1950s, becoming one of the few crossover Black stars in a segregated nation. His songs, including “Day-O (Banana Boat Song)” and “Jump in the Line,” brought calypso music to American audiences and became enduring hits, while his powerful screen presence propelled films like Carmen Jones and Island in the Sun. At venues across the country — from Carnegie Hall to Caesars Palace — he captivated Black and white audiences with his ability to inject both deep pathos and impish humor into a globally expansive repertoire.

But at the height of his mainstream fame, Belafonte stepped back from entertainment to devote the bulk of his time to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. He became a key economic engine and behind-the-scenes organizer for many of the sit-ins, freedom rides and marches that would sweep the South and propel social and federal change. He raised and personally delivered $70,000 to protestors in Mississippi during their Freedom Summer in 1964, under a blaze of gunshots from the Ku Klux Klan; he became one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s most trusted confidants, serving as a mediator between King and John F. Kennedy’s White House; he stood at the front lines at the March on Washington and the final march from Selma to Montgomery.

In the decades to come he would expand his empathetic push to a global scale, fighting against apartheid in South Africa, famine in Ethiopia, and genocide in Rwanda. He became a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, spearheaded “We Are the World,” and railed fiercely against the Iraq War.

His musical and political efforts earned him a Kennedy Center Honor, a National Medal of Arts, a Grammy, a Tony and an Emmy. He remained a devoted and relentless activist up until his death. “There was never a performer who crossed so many lines as Harry,” Bob Dylan wrote in his 2004 memoir.

More from TIME

From a violent childhood to the theater

Belafonte was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in 1927 in Harlem, the son of Melvine (née Love), a housekeeper, and Harold George Bellanfanti Sr., a chef. Both of his parents were mixed-race undocumented immigrants who constantly changed jobs, apartments and even their names to avoid authorities. “Throughout my childhood we lived an underground life, as criminals of a sort, on the run,” Belafonte wrote in his 2011 memoir, My Song.

As a child, Belafonte spent several years in a mountain village in Jamaica where his grandmother lived (his mother sent him there because she deemed the island safer) and he would marvel at music’s centrality to the culture. “Almost all the songs that I later came to sing were songs that I heard among the peasants and the people of my family at that time,” Belafonte said in the 2011 documentary Sing Your Song.

While his time in Harlem was culturally rich — he would see Duke Ellington or Count Basie at the Apollo after Sunday Mass — it was rife with hardship and sorrow. His alcoholic father beat him bloody; his schoolyard years were full of fights waged with “bottles, garbage cans, rocks, hands and feet.” When he was a toddler, he accidentally cut himself in the eye with scissors, blinding himself in one eye for the rest of his life. Belafonte was also dyslexic, and his poor eyesight led him to drop out of school in the ninth grade, leaving him few career prospects.

He joined the Navy in 1944, hoping for adventure and glory on the Eastern front of World War II. But the armed forces were still segregated, with African Americans often relegated to dangerous grunt work like handling live ammunition. Belafonte himself served this role on the New Jersey coast — and despite his service he was often turned away from segregated restaurants or concert venues. “The all-too-frequent incidents of prejudice kept me in an almost constant state of simmering rage,” he wrote.

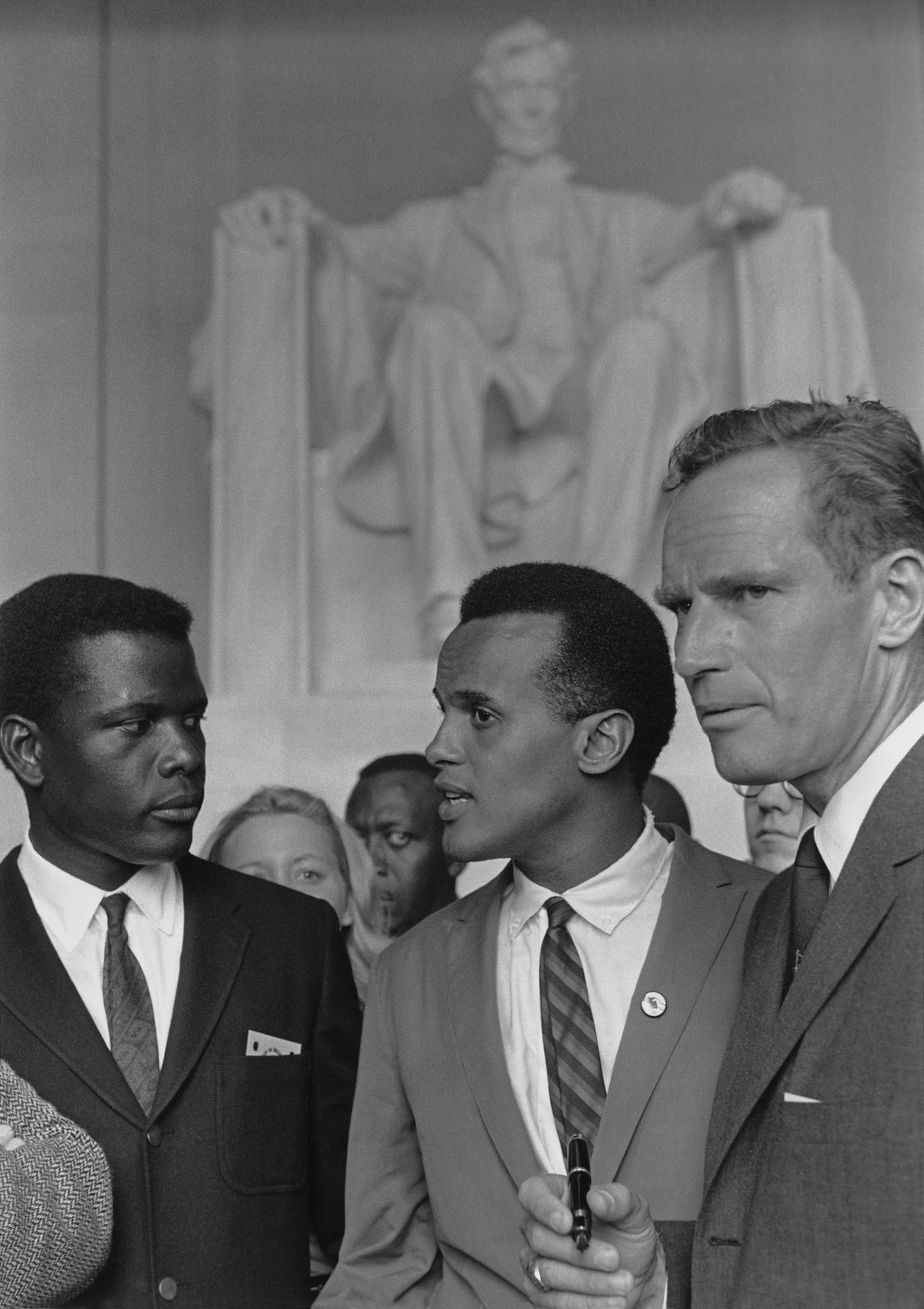

After 18 unhappy months, Belafonte’s Navy stint ended; he went back to Harlem and found work mopping halls and stoking furnaces as an assistant janitor in apartment buildings. One day, after hanging venetian blinds for a tenant, she gave him tickets to the American Negro Theater. That experience proved life-changing: Belafonte volunteered for the theater and found himself in a close-knit and vibrant community that encouraged his thespian instincts. In one of his first-ever roles, his understudy was a young unknown actor named Sidney Poitier. The pair would go on to share a deep friendship, albeit one laced with rivalry, for the rest of their lives.

Belafonte enrolled in the Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research thanks to the G.I. Bill, where his classmates included Marlon Brando, Bea Arthur and Walter Matthau. But while the rest of his class began landing significant roles in the New York theater world, Belafonte found the opportunities for a Black man extremely limiting or nonexistent. While Belafonte scrounged for acting work and pushed clothing racks in the Garment District, he and his newlywed wife, Marguerite Byrd, lived on her teacher’s salary in a $55-a-month apartment.

It was during this dry spell that the saxophonist Lester Young encouraged Belafonte to start singing to help tide him over. Belafonte’s first gig was at the Royal Roost — a renowned jazz haunt where he spent many of his evenings — and the backing band, to his complete surprise, included the jazz legends Max Roach and Charlie Parker. “I could never repay them, not then or later, for this amazing act of generosity,” he wrote of them.

Buoyed by their support, Belafonte drew an enthusiastic audience response, and soon landed gigs at the Village Vanguard, then at venues in Miami and Las Vegas. His repertoire was eclectic: jazz standards, chain gang chants, calypso, and folk songs, many of which he found while combing through Alan Lomax’s field recordings at the Library of Congress. While his material was diverse, the quality of his performances was uniformly electric. His acting training led him to sing with impassioned conviction and precise diction; he fully embodied the narrator of each song, whether in “Hava Nagila” or “On Top of Old Smokey.” His charisma, good looks and racial ambiguity — he could sometimes pass for white — made him a hit in front of diverse sets of crowds across the country.

But Belafonte was still met with plenty of resistance, especially as he entered previously segregated spaces. While walking up Coldwater Canyon while filming his first Hollywood role, Bright Road, he was arrested and charged with illegal loitering. In Las Vegas, he was turned away from the resort he was playing at and instead told to stay at a dingy colored motel across town. A Chicago club’s manager initially refused to let him into his own show.

‘America’s Negro matinee idol’

Despite the constant blockades, Belafonte would soon reach the height of his performing career and become known as “America’s Negro matinee idol.” He starred in films including Carmen Jones and Island in the Sun, and won a Tony in 1954 for the Broadway show John Murray Anderson’s Almanac. While performing in the traveling musical theater revue 3 For Tonight, he weathered death threats from the Ku Klux Klan in South Carolina and held hands with his white female counterpart during the show’s finale in segregated houses. “[Belafonte] represents the fanaticism of the dedicated artist,” Brooks Atkinson wrote in his 1955 Times review of the show. “His singing personality is vibrant and magnetic.”

In 1956, Belafonte decided to record an entire album of Caribbean island songs, much to the chagrin of his label, RCA, who felt it would be too “ethnic.” But Calypso was a runaway success: It made history as the first album to sell a million copies in the U.S., and embarked on a 99-week Billboard chart run that wouldn’t be matched until Michael Jackson’s Thriller more than a quarter-century later. The first song, “Day-O (Banana Boat Song),” with its dramatic a capella opening, became Belafonte’s signature song, and would be covered and sampled countless times, including in Tim Burton’s 1988 dark comedy Beetlejuice, and in Lil Wayne’s 2010 hit “6 Foot 7 Foot.”

On March 2, 1959, Belafonte appeared on the cover of TIME. That year, he would also star in two major films, Odds Against Tomorrow and The World, the Flesh and the Devil, and open a one-man show in Times Square. The following year he made history again by becoming the first African-American to win an Emmy — for his CBS special Tonight With Belafonte.

With his genial charm, Belafonte seemed to fit right into America’s celebrity crust. He gambled with Sinatra in Las Vegas, served as Sammy Davis Jr.’s best man during a sham wedding staged to protect Davis from the mob, and hosted Eleanor Roosevelt for dinner. In 1961, he gave Bob Dylan his first professional recording gig: a harmonica performance on “Midnight Special.” Years later, Belafonte would sing Dylan’s praises in his memoir Chronicles, Volume One, calling him “the best balladeer in the land.”

‘To change the culture, you had to change the country’

But amid these towering successes, Belafonte was also becoming increasingly frustrated with show business and its latent racism. In Hollywood, he was mostly offered staid, sedate roles like the curmudgeonly teacher or the well-meaning handyman. And in films that did match him with white love interests, those onscreen relationships were stripped of physical touch or sexual chemistry. “Doing battle with [television and movies] was like fighting a mirror,” Belafonte wrote in My Song. “To change the culture, you had to change the country.”

So Belafonte stepped back from his entertaining career and plunged into activism alongside his second wife, Julie Robinson, whom he married in 1957. Some of this work was small-scale and personal: After being turned away from many apartments on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, for instance, Belafonte simply bought an entire building and integrated it with black stars like Lena Horne and Ron Carter.

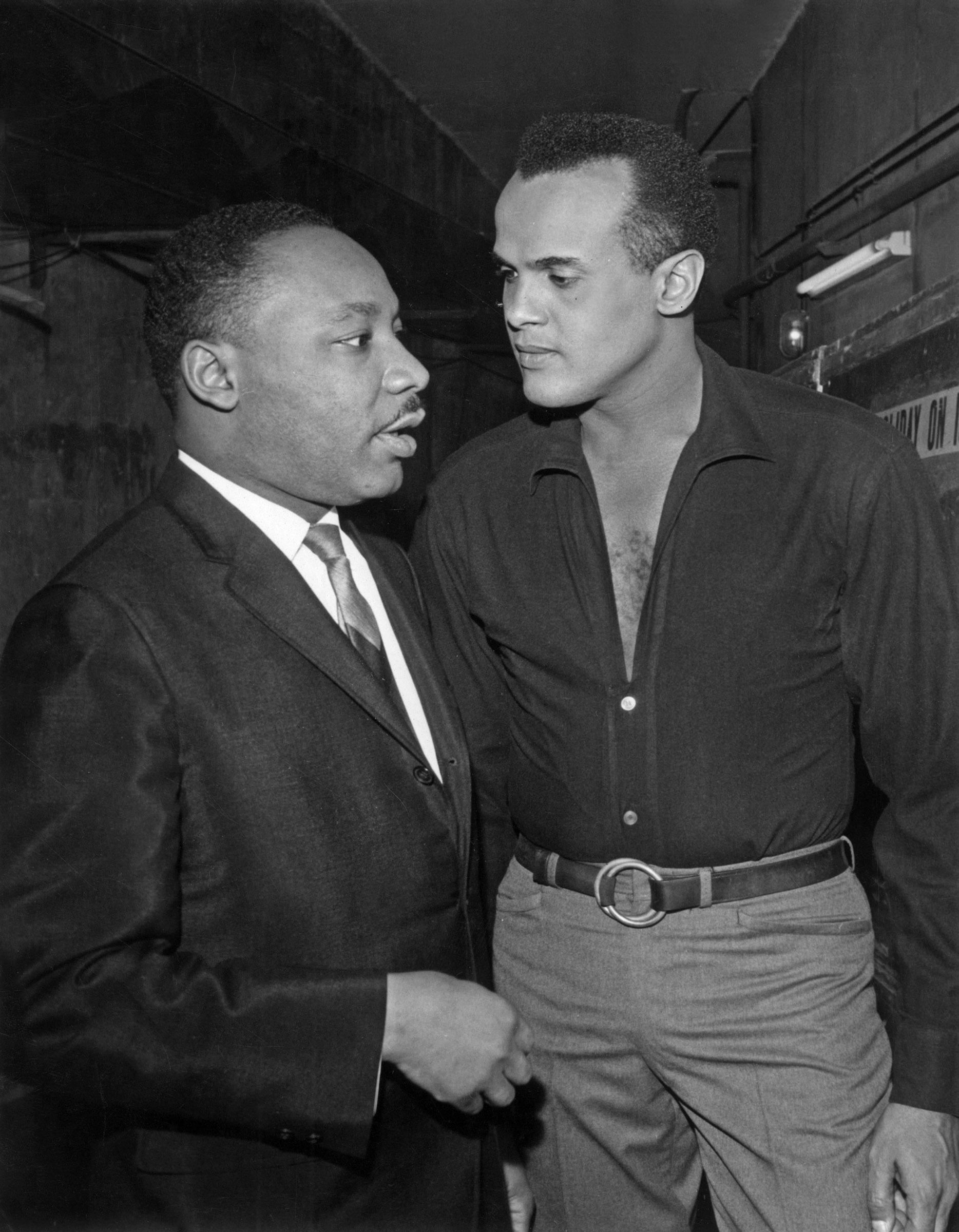

But Belafonte would also become a key figure in a national movement after meeting Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1956. At the time, King was a rising 26-year-old preacher leading the bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama; when he asked for Belafonte’s help in funding the boycotts, Belafonte started organizing house parties to raise funds. “I knew then I would forever be in his service,” Belafonte said in Sing Your Song of their first meeting.

Two years later, Belafonte helped lead a group of ten thousand students in a march on the White House for desegregation. In the immediate wake of the Birmingham protests in 1963, when thousands of children were jailed by Bull Connor’s police forces, he raised hundreds of thousands of dollars and worked closely with King, Attorney General Robert Kennedy and union leaders to bail scores of children out of jail.

Belafonte also wrangled star power for the 1963 March on Washington, which included Tony Bennett, James Baldwin and Lena Horne. “It wasn’t just that they were sympathetic and very much involved in the ideals of the struggle. It was that, that’s who they were,” Belafonte told TIME in 2013 for the march’s 50th anniversary.

Later, he organized a “Stars for Freedom” rally at the third march from Selma to Montgomery with Nina Simone, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Joan Baez. In 1964, he and Poitier flew $70,000 in cash to Mississippi to support their Freedom Summer and whizzed down the highway as a pursuing phalanx of the Ku Klux Klan fired gunshots at them.

An activist to his core

Belafonte eventually became one of King’s closest friends and confidants, hosting meetings, serving as a liaison between King and the Kennedys, and even paying for the preacher’s housekeeper, driver and secretary. In 1968, King appeared as a guest on The Tonight Show when Belafonte took over for Johnny Carson for a week, waxing about economic inequality and cracking jokes about his fear of airplanes.

“Whenever we got into trouble or when tragedy struck, Harry has always come to our aid, his generous heart wide open,” Coretta Scott King wrote of Belafonte in her autobiography.

While Belafonte helped fight national battles, he also turned his focus abroad, particularly to injustice in Africa. He fought against apartheid in South Africa for decades, serving as a mentor to one of the country’s most prominent voices of protest, Miriam Makeba, and then coordinating Nelson Mandela’s first trip to the United States in 1990. In 1984, Belafonte spearheaded “We Are the World,” which raised over $63 million for humanitarian aid, and then worked to distribute the funds across the African continent.

Three years later he was named a UNICEF goodwill ambassador. He made trips to Senegal, war-torn Rwanda, South Africa and Kenya, raising awareness for starvation, the lack of education and HIV prevention. In 2002, Africare awarded him the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Award.

All the while, Belafonte continued to release music and appear in films. In 1972, he shared the screen with Poitier in the acclaimed Buck and the Preacher, playing against type as a shifty minister. He delivered an iconic and beloved performance of “Turn the World Around” on The Muppet Show in 1977. In 1996, he received raves for his supporting role in Robert Altman’s Kansas City.

The father of four retired from performing in 2007, and married third wife Pamela Frank a year later. Even into his 80s and 90s he remained squarely in the public eye, especially due to his incendiary rhetoric about political and social issues. He railed against the Iraq War, calling Colin Powell the “house slave” of the Bush administration. He organized music festivals to raise awareness for voting and mass incarceration. He championed Cuban rap to Fidel Castro. He opened up a dialogue about the role of the celebrity when he admonished Jay-Z and Beyoncé for turning “their back on social responsibility.” In 2017, he even co-chaired the Women’s March following Donald Trump’s election.

“Had I not been led to a place of activism, nothing in my life would have been worth its existence,” he told TIME in 2017 while sitting beside Gloria Steinem. “All these people made my life absolutely a tarantella — it’s a dance. It’s a place to be so privileged to be in.”

Belafonte is survived by his wife Pamela, four children, two stepchildren, and eight grandchildren.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com