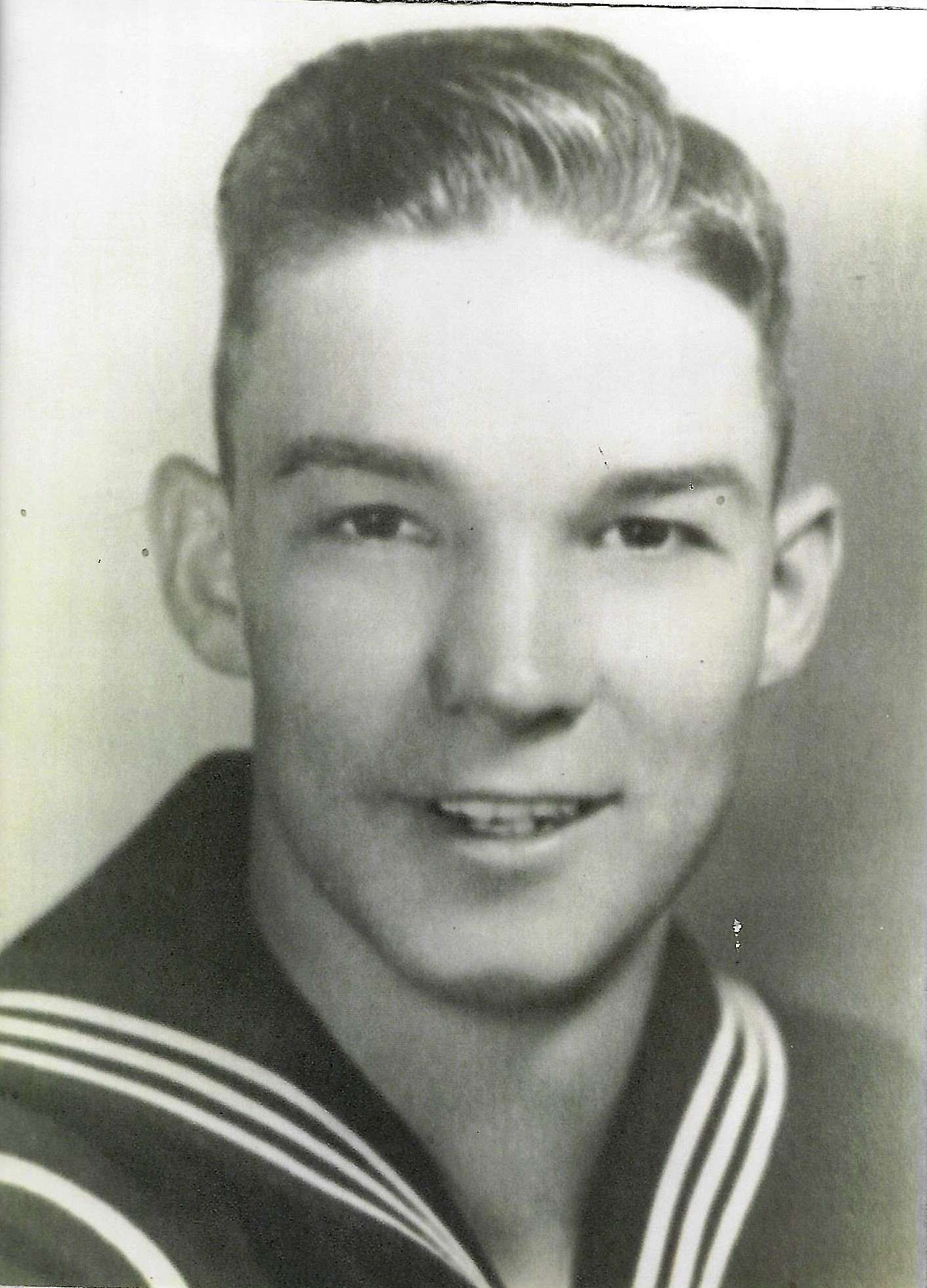

Victor Patrick “Pat” Tumlinson was always a shadow in the background of his nephew James Patrick Tumlinson’s life. Victor was just 19 when he died alongside 428 others on the battleship U.S.S. Oklahoma in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 — nearly a decade before James was born. But, the relatives were connected by the same birthday, Jan. 28, and the same middle name and nickname — “Pat.”

Reminders of Victor also lingered in his hometown of Raymondville, Texas. The local Veterans of Foreign Wars post was named after him, and the family inscribed his name on a gravestone in the local cemetery next to his mother, but the ground beneath remained empty.

That’s because Tumlinson’s remains were unidentified for nearly eight decades — just one of more than 1,300 U.S. personnel from Pearl Harbor who are confirmed dead, but whose remains have still not been identified and brought home. Along with many others who perished on the Oklahoma, his name was marked on a plaque at the National Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, but an individual burial was impossible.

For most Americans, Pearl Harbor is remembered as one of the great turning points in U.S. history. After the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor claimed the lives of 2,403 U.S. civilians and service members and destroyed or damaged 21 ships, the U.S. was pushed to join World War II. But for families like the Tumlinsons, in some ways the story appeared to be permanently unfinished.

That is set to change on Saturday — Pearl Harbor Day — when Tumlinson will finally be laid to rest in the place where he grew up.

For decades, Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency and its predecessors have worked to identify those killed in the Korean War, Vietnam War and other conflicts. Thanks to their hard work and scientific innovations — like DNA testing — investigators have started to look even further back: to the Pearl Harbor dead and others from World War II.

With each passing conflict, the Department of Defense scientists gradually fine-tuned their ability to gather information from human remains, and increasingly started to incorporate DNA-testing technology. Today, Department of Defense DNA Operations, in collaboration with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, can compare genetic information from family members to DNA gathered from service members’ remains, including some that have been degraded or commingled.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, recovering the remains required months of work; many were not removed from the ship until months after it sank.

In the 1940s, researchers who were trying to match the remains with the names of missing sailors were limited to the forensic methods of the era, like dental records. Identifying remains recovered from the Oklahoma seemed to be particularly challenging, because they had been badly mixed together as they were removed from the ship. It was ultimately decided that it would be too difficult to tell apart the remains, some of which had spent years in the water.

Ultimately, only 35 crew members — out of the 429 Navy personnel and Marines who died on the ship — were positively identified in the years immediately after the Oklahoma sank. The other remains were buried as unknowns in the National Cemetery of the Pacific by 1950.

In the decades since the attack, Tumlinson’s three surviving siblings went on to have their own children who grew up hearing stories of their uncle.

“He was the tender-hearted one,” says his niece Rose Young. “I was always left with the feeling that I wish I could have known Uncle Pat. [He was] smart, and he was the younger one so he would be fun to be with.”

The family was also left with precious artifacts from Victor’s life: a puzzle that he had crafted out of wire; a wooden heart he’d given to a girlfriend that had later been passed on to his mother; and one of the last letters he wrote home on Thanksgiving Day, 1941 — little more than two weeks before his death.

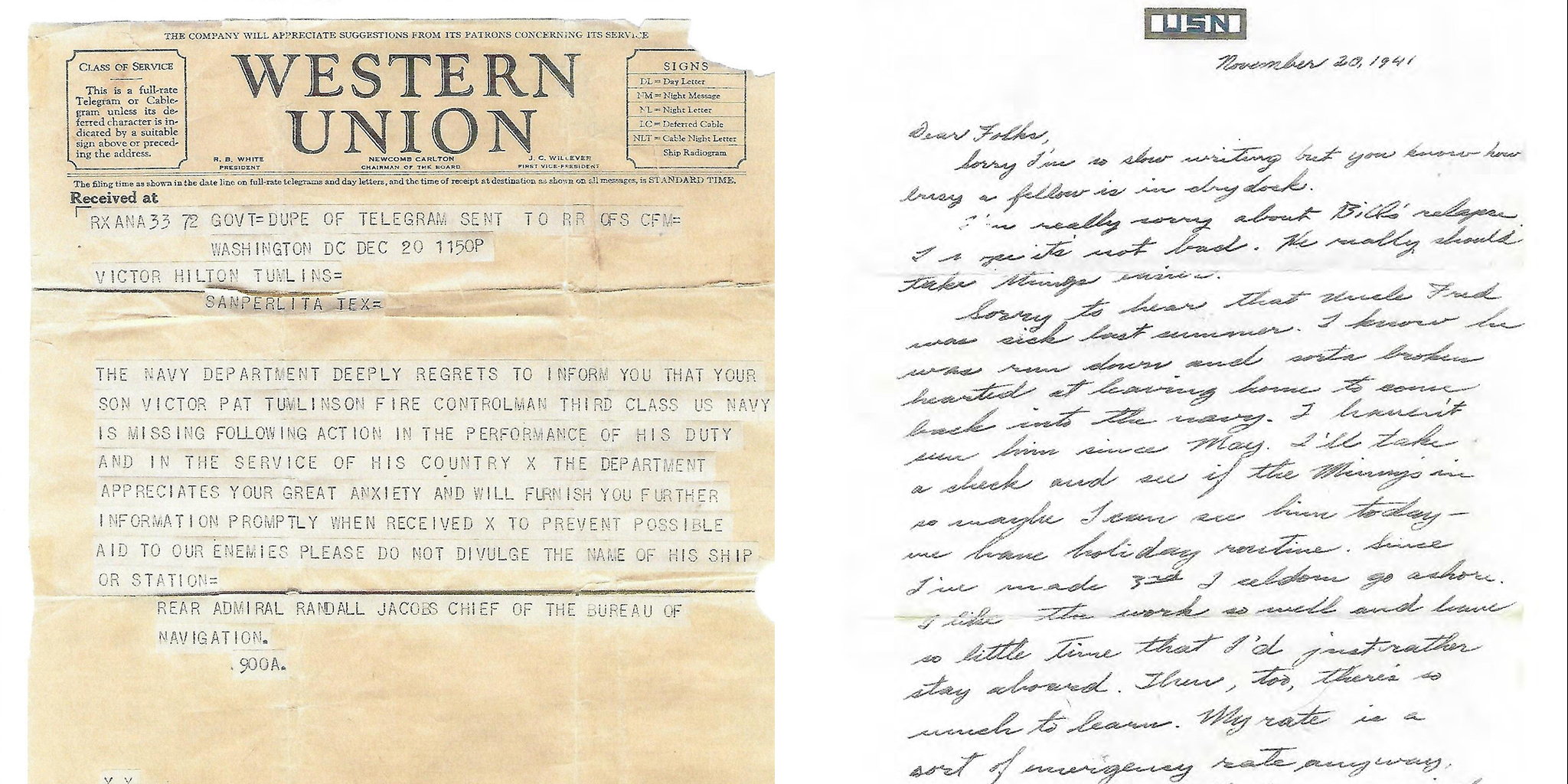

In the letter, Tumlinson apologized for not writing more often, reminding his family that he was busy while the ship was in dry dock. He mentioned that the U.S.’s Atlantic Fleet seemed to be “pretty close” to war, but wrote mostly about his family — including his brother, Sam, who was in the Army — and talked about the upcoming University of Texas-Texas A&M football game. He told his family that he liked his work since his rank had been changed, saying he was glad that in his new role he got to be out in the open instead of deep below deck.

“From the way you talk about the fresh sea air, etc. I see you don’t understand sea life. Sure the air is fresh, etc. at sea but just picture 1,600 men on one ship and figure how crowded a ship is,” Tumlinson wrote. He signed the letter, “Love, Pat.”

The family also kept two telegrams: one from Dec. 20, informing them that Tumlinson had gone missing, and a second announcing that he had been declared dead.

“After exhaustive search it has been found impossible to locate your son Victor Pat Tumlinson Fire-Controlman Third Class US Navy and he has therefore been officially declared to have lost his life in the service of his country as of December Seventh Nineteen Forty One. The Department expresses to you its sincerest sympathy,” said the letter, which was signed Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs.

Tumlinson’s death was especially hard on his mother, who had also buried the family’s youngest daughter after the girl drowned.

“It was probably the hardest on her. She had lost her baby girl and lost her baby boy,” says James Patrick Tumlinson.

Cathy Ayers, Tumlinson’s niece, says that her grandmother never really got over losing her son. “Until the day she died, she said, ‘I wish they could bring my boy home,” Ayers says.

Finally, nearly eight decades after the remains were buried, families like the Tumlinsons were given new reason for hope.

In 2003, a Pearl Harbor survivor named Ray Emory approached the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory with records that suggested one of the 61 caskets that held the remains of unknown Oklahoma sailors contained the remains of a particular service member killed in Pearl Harbor. The Lab agreed to investigate, and the casket was exhumed.

Forensic analysis of the remains discovered something surprising: the traces of about 100 people in the single casket.

Timothy McMahon, the director of Department of Defense DNA Operations, tells TIME that DNA and other identification technologies have evolved rapidly in the past few decades as the military has pursued more identification projects, including for people who perished in the Korean War. The technique was used to help identify service members from the Korean War, whose remains were returned to the U.S. by North Korea in 55 boxes last year.

The success of these projects and the DNA analysis of the USS Oklahoma coffin helped to convince the military that it was worth looking at other mixed-up remains from World War II, says McMahon.

“It all started with the USS Oklahoma and that large, first disinterment,” says McMahon.

In 2010, Congress added identifying the remains of World War II dead to the accounting agencies’ mission—in part because of the momentum generated by the USS Oklahoma mass coffin, according to McMahon. In 2015, the other coffins containing remains from the USS Oklahoma were exhumed. More than 200 individuals from the ship have been identified just in the last four years.

After that first coffin was dug up, descendants of Tumlinson’s sister, including Cathy Ayers, were asked to give mitochondrial DNA samples to compare with remains. Then, earlier this year, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency informed some family members that they had finally found a match.

“I was overwhelmed,” Ayers says. “I thought it was not ever going to happen.”

On Saturday, several dozen of Tumlinson’s family members and an honor guard detail will recognize Pearl Harbor Day by laying him to rest beside his mother in Raymondville.

“At the end of the day, that’s where he belongs,” said James Patrick Tumlinson.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com