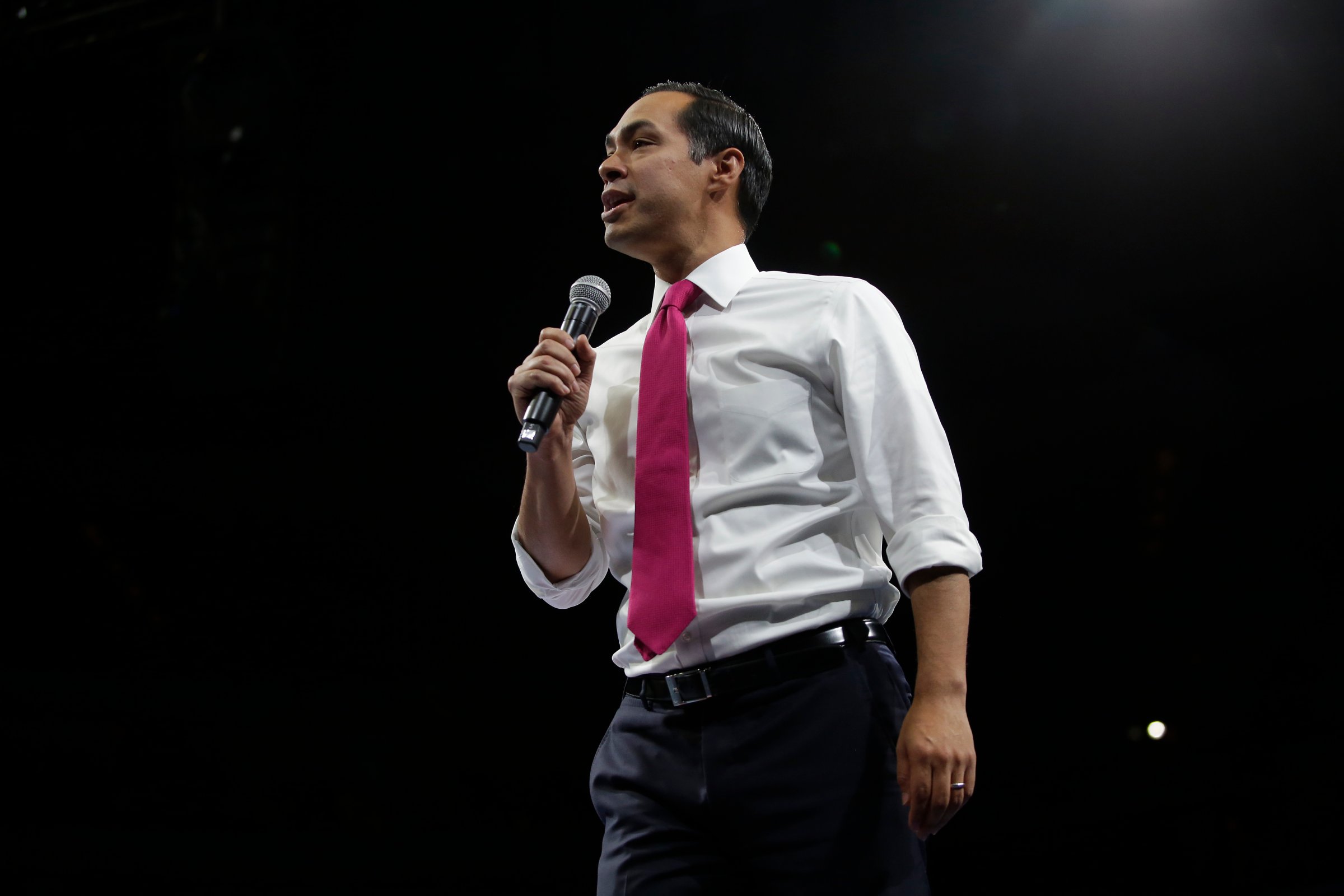

Julián Castro on Wednesday became the latest Democratic presidential candidate to unveil a policy aimed at expanding the rights of people with disabilities, promising to help the more than 60 million disabled Americans access “dignified work, decent housing, quality education, affordable health care, to live independently and achieve self-sufficiency.”

The plan says it will build on the promise of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by proposing a number of reforms to Social Security, advocating for employment opportunities, fully funding education for people with disabilities, and improving how disabled people are treated in the criminal justice system, among other ideas.

“The ADA is referred to as the ‘Emancipation Proclamation for People with Disabilities’ and provided reasonable accommodations for those with disabilities and banned discrimination against them in employment, housing, and public spaces,” Castro wrote in a Medium post on Wednesday announcing the policy. “Yet despite the important progress over the last three decades, disparity and poverty is still all to common in the disability community.”

Castro’s plan would raise the minimum wage to at least $15 an hour and end the sub-minimum wage by eliminating the provision of the Fair Labor Standards Act that allows employers to pay people with disabilities below the federal minimum wage. He would also increase government subcontracting with disabled-owned businesses and boost funding for the vocational rehabilitation system that helps disabled people find jobs.

The plan calls for universal pre-k and early support programs, a teacher tax credit and increased teacher training, reforming the school discipline system to end corporal punishment and remove police officers, and fully funding the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Many of Castro’s Democratic rivals have also said they would fund the federal government’s share of the IDEA, which Congress has never done. South Bend, Ind. Mayor Pete Buttigieg also released a detailed disability plan earlier this month, and California Sen. Kamala Harris released her own plan in August. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders each have disability rights sections on their campaign websites and have included people with disabilities throughout their other plans as well.

While one in four U.S. adults has a disability, they often do not receive much attention from national politicians, in part because voter turnout has historically been low and because disabled Americans have not been seen as a community in the way that other minority groups have been. But under the Trump administration, disabled Americans have played an increasingly prominent role in activism around health care and other issues, and voter turnout among people with disabilities surged in the 2018 midterms, suggesting they could play a key role in 2020.

Castro addressed this history in his announcement. “Listening to people with disabilities, it’s clear that that politicians in Washington have ignored these challenges,” he wrote. “We need a new generation of leadership with bold solutions to lift up people that have been left out.”

After none of the 2020 presidential candidates started the cycle with accessible campaign websites, the group has been improving, and many have paid more attention to the disability community than in previous elections.

Beyond employment and education, Castro’s disability plan emphasizes proposals that would expand inclusion and civil rights for people with disabilities. The plan would double federal investment in public transportation, build at least 3 million affordable housing units and reinstate a fair housing rule that Castro created when he was President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development but has since been repealed under Trump.

Castro’s plan includes several health care proposals, including a commitment to support disabled Americans’ ability to live in their own communities instead of relying on institutions. He would also expand Social Security Disability Insurance and Social Security Insurance benefits, eliminate the “benefit cliff” that currently means SSDI recipients lose their benefits if they earn over a certain income threshold. Notably, Castro calls for eliminating asset limits on SSI and ending penalties in the current system that can make it difficult for some people with disabilities to get married and retain their benefits.

The plan also calls for making elections more accessible, and proposes a number of criminal justice reforms. People with disabilities are more likely to be victims of sexual assault and spend time in prison, and research has found that many people killed by police have disabilities, and Castro’s plan aims to address these issues. He promises to boost funding for programs like the Violence Against Women Act, expand training for police officers to recognize mental illness and disabilities, work to prevent violence against disabled people in prisons and make courts more accessible to people with disabilities.

Castro’s plan is one of the most far-reaching disability proposals of any candidate in the field, but the former HUD secretary has struggled to gain much traction with his presidential campaign despite putting out a slate of progressive policies. This latest policy comes after a trip to Iowa during which Castro held a roundtable discussion about disability issues on Monday and made headlines for saying that Democrats should rethink their first primary states because Iowa and New Hampshire do not reflect the party—or the country’s—diversity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com