On a recent Saturday morning in Washington, D.C., about two dozen secondary-and-elementary-school teachers experienced a role reversal. This time, it was their turn to take a quiz: answer “true” or “false” for 14 statements about the famous meal known as the “First Thanksgiving.”

Did the people many of us know as pilgrims call themselves Separatists? Did the famous meal last three days? True and true, they shouted loudly in unison. Were the pilgrims originally heading for New Jersey? False.

But some of the other statements drew long pauses, or the soft murmurs of people nervous about saying the wrong thing in front of a group. Renée Gokey, Teacher Services Coordinator at the National Museum of the American Indian and a member of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, waited patiently for them to respond. The teachers at this Nov. 9 workshop on “Rethinking Thanksgiving in Your Classroom” were there to learn a better way to teach the Thanksgiving story to their students, but first, they had some studying to do. When Gokey explained that early days of thanks celebrated the burning of a Pequot village in 1637, and the killing of Wampanoag leader Massasoit’s son, attendees gasped audibly.

“I look back now and realize I was teaching a lot of misconceptions,” Tonia Parker, a second-grade teacher at Island Creek Elementary School in Alexandria, Va., told TIME.

It can sometimes seem that the way kids are taught about Thanksgiving, a staple of American education for about 150 years, is stuck in the past; an elementary school in Mississippi, for example, drew backlash for a Nov. 15 tweet that included photos of kids dressed up as Native Americans, with feather headbands and vests made of shopping bags. But the approximately 25 teachers at that Washington workshop were part of a larger movement to change the way the story is taught.

“I believe it is my obligation as an educator,” said Kristine Jessup, a 5th-grade teacher at Brookfield Elementary School in Chantilly, Va., “to ensure that history does not get hidden.”

The Thanksgiving story that American schoolkids have typically learned goes something like this: the holiday commemorates the way the pilgrims of Plymouth, Mass., fresh off the Mayflower, celebrated the harvest by enjoying a potluck-style dinner with their friendly Indian neighbors. In many classrooms, the youngest children may trace turkeys with their hands to mark a day for feasting, or dress up as pilgrims and Indians for Thanksgiving pageants. Older kids may study the reasons the pilgrims crossed the Atlantic and how their endurance fostered America’s founding values.

But, while the meal known as the First Thanksgiving did happen—scholars believe it took place at some point during the fall of 1621 in the recently-founded Plymouth colony—that story reflects neither the 17th century truth nor the 21st century understanding of it. Rather, the American public memory of Thanksgiving is a story about the 19th century.

What really happened back in the fall of 1621 is documented in only two primary sources from colonists’ perspectives. Edward Winslow’s account of the bountiful harvest and the three-day feast with the Wampanoag people runs a measly six sentences, and Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford’s later account is about the same length—evidence, argues historian Peter C. Mancall, that neither colonial leader considered the event worth more than a paragraph. As Plymouth became part of Massachusetts and Puritans gave way to the Founding Fathers, nobody thought much about that moment. When George Washington declared a national day of Thanksgiving in 1789, his proclamation of gratefulness made no mention of anything related to what happened in Plymouth. Then, around 1820, a Philadelphia antiquarian named Alexander Young found Winslow’s account. He republished it in his 1841 Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers, with a fateful footnote: “This was the first Thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England.”

In the years that followed, Godey’s Lady’s Book editor Sarah Josepha Hale—who might be thought of as the 19th century’s Martha Stewart—began advocating for the establishment of an annual national Thanksgiving holiday. When Bradford’s account of 1621 was rediscovered in the 1850s, the timing was fortuitous, as the divided nation hurtled toward Civil War. Hale’s message got through to Abraham Lincoln, and in 1863, with the war underway, he issued the proclamation she’d wanted, arguing that Americans should “take some time for gratitude” in the midst of the bloodshed. Crucially, Hale’s campaign for the Thanksgiving holiday was explicitly linked to the story of Plymouth.

But the fact that so little was actually written about that 1621 meal left a lot open to the imagination.

In reality, the gathering was neither the first encounter between the colonists and the Native Americans, nor was it purely a happy moment. A mysterious epidemic, spread through contact with the Europeans, had decimated the Wampanoag population, so they reached out to the English at Plymouth, “because they wanted allies and access to European military weapons” in case they needed to defend themselves against their rivals, the Narragansett, according to historian David J. Silverman, author of the new history This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. And while it’s true that the famous meal in 1621 was peaceful, it did not last. War between the settlers and Wampanoag broke out in the 1670s.

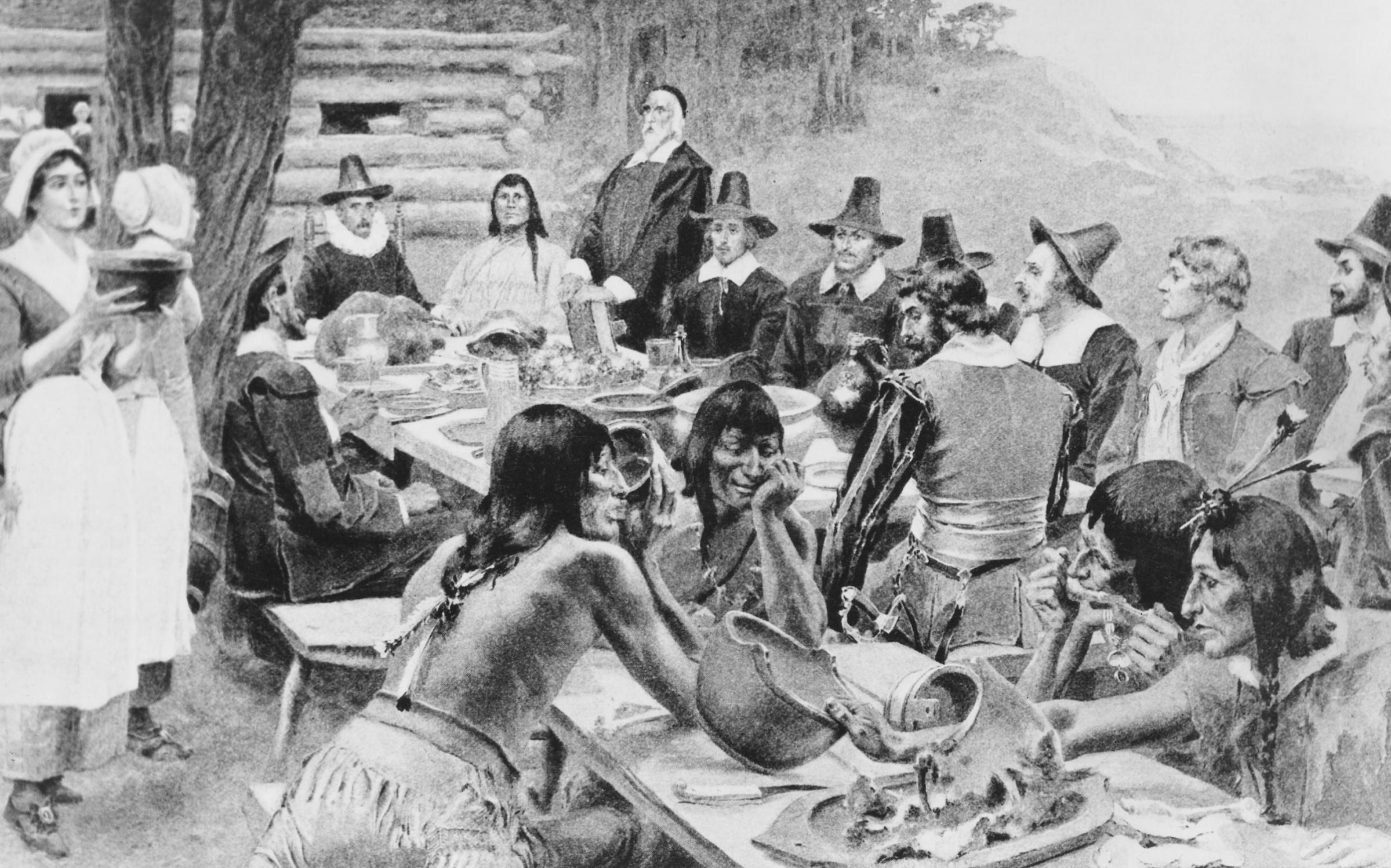

But that’s not what was included in the classroom materials about Thanksgiving that began to be developed in the wake of Lincoln’s proclamation, especially between the 1890s and 1920s, according to former Plimoth Plantation historian James W. Baker’s Thanksgiving: The Biography of an American Holiday. The settlers were re-branded the “pilgrims.” An 1889 novel Standish of Standish: A Story of the Pilgrims by Jane G. Austin, which described “The First Thanksgiving of New England” as an outdoor feast, became a best-seller. In 1897, an illustration by W.L. Taylor of a meal like the one Austin described accompanied a piece in Ladies Home Journal that was presented as a factual article about the first Thanksgiving; thanks in part to the growth of the advertising industry at this time, variations of this image spread quickly.

Those images made their way into classrooms too. The Nov. 2, 1899, issue of the Journal of Education recommended Austin’s novel and the Ladies Home Journal piece in a list of reference materials related to Thanksgiving, and Taylor’s illustration appeared in an educational booklet for teachers to hand out to students. To make the sentimental stories of the peaceful, friendly relationship between colonists and Native Americans more memorable, teachers developed skits and plays for students to perform, drawing in part on depictions of Native Americans in early Western films. By the 1920s, Thanksgiving was the most talked about holiday in classrooms, a survey of elementary school principals revealed. The parts that made the colonists look bad were left out.

The holiday’s popularity in classrooms was no coincidence. The arrival of large numbers of Jewish, Catholic and Asian immigrants to the United States around the turn of the 20th century, as well as rapid urbanization, led to a surge of both nativism and nostalgia. Genealogical organizations were formed to celebrate American families that could trace their lineage back to the colonial era, such as Daughters of the American Revolution and the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, and one 1887 cartoon compared noble-looking pilgrims confidently striding off the Mayflower in 1620 to the huddled masses of the time. In the 1940s and ‘50s, as the Cold War drove another wave of concern about threats to the American way of life, Thanksgiving-themed imagery of pilgrims once again exploded.

In some schools, Thanksgiving became one of the only times Native Americans were discussed, often leaving students with a mistaken, and damaging, impression. “There’s a widespread assumption that Indians have disappeared,” says Silverman. “That’s why non-Native Americans feel comfortable dressing up their kids in costumes.” In reality, there are 573 federally-recognized tribes today, and active American Indian culture and communities can be found all across the country. After the civil rights movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s, which included the growth of the American Indian Movement, the dissonance between that reality and the common story of Thanksgiving got harder to ignore.

Even so, half a century later, many classrooms are only beginning to change.

Through Twitter, Facebook groups and shared Google docs, teachers have been trading ideas on how to do Thanksgiving right. The young readers’ edition of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, adapted by Jean Mendoza and Debbie Reese, was released in July 2019. Larissa FastHorse, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in the Sicangu Lakota Nation, drew on the memory of feeling “dehumanized” during classroom activities, she tells TIME, when she wrote her 2015 The Thanksgiving Play, which has become one of the most produced plays in the United States. And in a Medium article posted last year, historians who are moms banded together to aggregate resources that parents can suggest teachers use, including templates for emails to express concerns about stereotypical pageant costumes. Lindsey Passenger Wieck, a Professor of History and Director of Public History at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas, says she put it together so that no parent would feel as mortified as she did when her 4-year-old son walked onstage in a feathered headband at his daycare’s Thanksgiving production in South Bend, Ind.

The parents who contributed to the Medium round-up say that whenever they raised concerns or suggested resources, teachers and administrators were receptive. But these success stories are not the rule. Some Thanksgiving-themed school activities and plays listed on Pinterest and the lesson-plan website Teachers Pay Teachers include activities that promote the same old stereotypical costume designs.

Efforts to improve went viral last year when Lauryn Mascareñaz, Director of Equity for the Wake County Public School System in North Carolina, tweeted her frustration with Facebook friends proudly sharing pictures of their children in stereotypical Native American costumes.

Since then, teachers and administrators have reached out to her for gut checks about making their Thanksgiving lessons more culturally sensitive—but, she says, she has also received equal amounts of hate mail questioning her patriotism.

Elementary schools present a particularly tough challenge, explains Noreen Rodriguez, a professor of Elementary Social Studies at Iowa State University, in part because the teachers are less likely to have advanced degrees in the subject matter—their coursework is more likely to have been about pedagogical methods, not content—and are thus more likely to fall back on memories of what they themselves learned in school. Zipporah Smith, a third-grade teacher in Des Moines, says some colleagues have been reluctant to update Thanksgiving lessons because they have “such fond memories of the Thanksgiving activities they did in school.”

“The most dangerous phrase in education is, ‘But we have always done it this way,’” echoes Mascareñaz.

The problem is further compounded by the growing gap between the demographics of students and teachers: About 80% of public school teachers were white in the 2015-2016 school year, while a record 51% of public school students were non-white, according to the most recent federal statistics on teacher diversity gap. In addition, standardized tests can be slower to change, and can in turn dictate what teachers actually spend time on.

Many teachers, however, know that change is coming, no matter how they’ve done it before. As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, efforts to diversify curriculums have gotten more attention. State social studies standards increasingly prompt students to look at history, including that of Thanksgiving, from multiple perspectives.

Plus, teaching a better lesson about gratitude is something everyone can get behind. At the workshop in Washington this month, after learning something new, participants learned to say Wado. That’s Cherokee for “Thank you.”

A version of this article appears in the Dec. 2-9, 2019, issue of TIME

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com