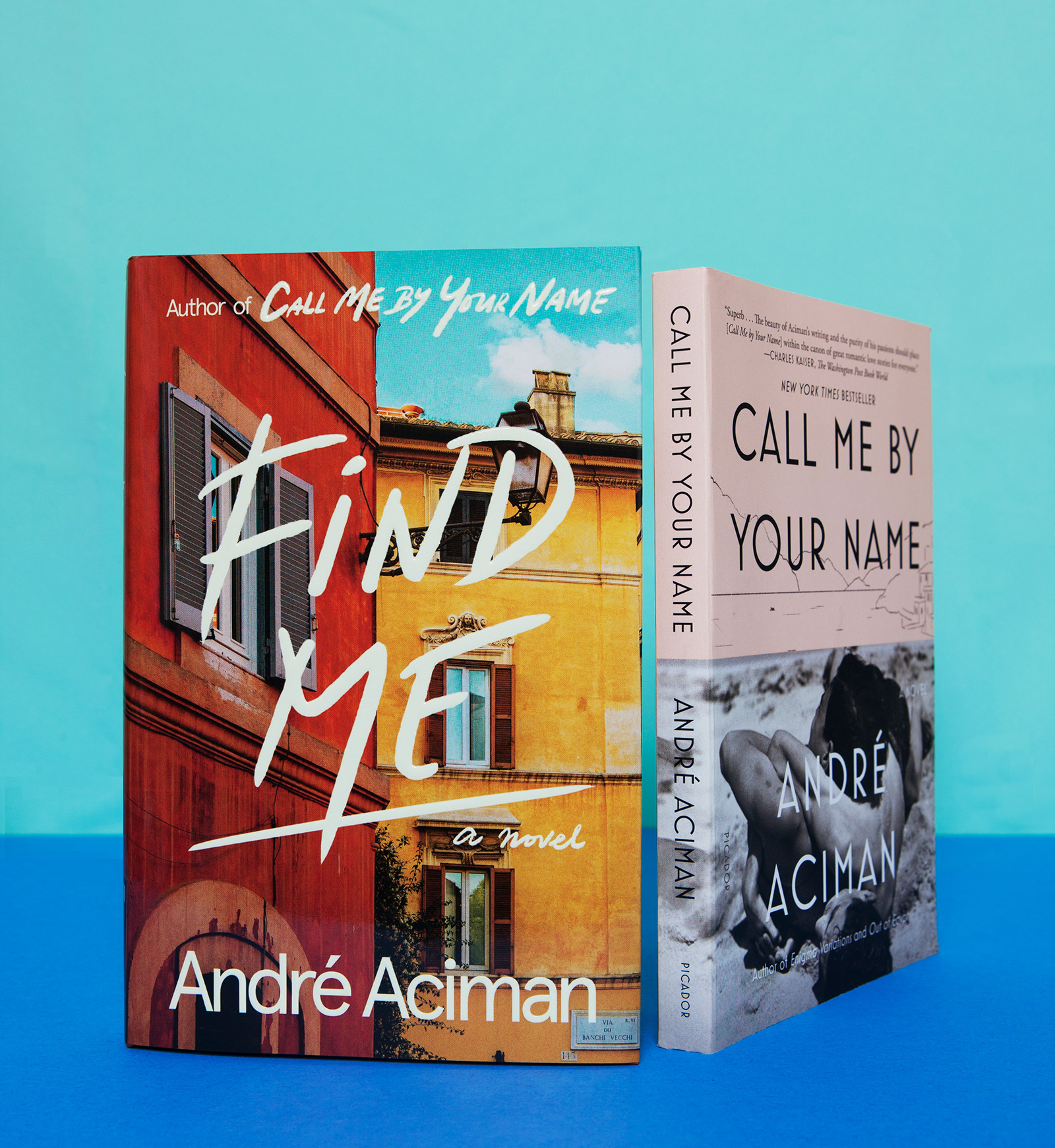

André Aciman wasn’t entirely honest with us. In late 2017, around the release of the film adaptation of his cherished 2007 novel Call Me by Your Name, he indicated that he’d closed the book on his characters Elio and Oliver, the star-crossed lovers at the center of the story. “I’ve said what I had to say,” he told a reporter when asked about a potential sequel. But Aciman had been working on a follow-up for over a year.

Now, as he prepares for the Oct. 29 release of Find Me, his new book set in the world of Call Me by Your Name, Aciman settles in his New York City apartment to come clean. “I wasn’t sure,” he says. “And I didn’t want to use the word, which became poisonous, sequel.”

It’s easy to see why Aciman might be wary of the pressure that comes with a sequel. Though his novel was acclaimed upon its release, garnering him a Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction, the movie, directed by Italian filmmaker Luca Guadagnino, turned his story into a phenomenon. Ten years after the book’s initial release, it finally landed on the best-seller list, and Aciman’s publisher says 800,000 copies have now been sold in the U.S. and Canada. Such a definitive account was Guadagnino’s film that when Aciman thinks of Elio and Oliver, he sees actors Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer. He says he tried to put their faces out of his head when writing Find Me, not wanting to be influenced by Guadagnino’s storytelling, and was able to do so because so much time has passed in Elio and Oliver’s world.

But readers hoping purely for another Elio and Oliver story may be disappointed. Aciman points out that Find Me, his fifth novel overall, is not an “obvious sequel” to Call Me by Your Name because it focuses significantly on a secondary character from the original book. More than 100 pages pass in Find Me before Elio appears in the flesh, and it takes Oliver considerably longer. The author tried for years to jump back into their lives in a more direct way. “I started with Elio — now he’s 21 or 22 years old and he’s in his third year of college, blah blah blah,” Aciman remembers. “I said, ‘This is too stupid. It’s not working.’ I figured I’d better give up.”

Then, in 2016, he met a woman on a train. She asked him to mind her dog while she used the bathroom, and he found her compelling enough to write a scene around. Within three pages of starting, Aciman realized he had shifted focus from the dog owner to Elio’s father Samuel and commenced official re-entry into this verdant world.

Find Me begins with that scene, of the now-single Samuel describing an encounter on a train with a woman about half his age, named Miranda. He’s on his way to visit Elio, now an accomplished pianist, in Rome. Ten years have passed since the magical summer when 17-year-old Elio and 24-year-old Oliver fell in love, and although life has taken them apart, they are still on each other’s minds. Where the first novel features a breathless internal monologue of rapture and anxiety, Find Me is more concerned with lovestruck conversations between burgeoning couples. The real woman got off Aciman’s train after a few stops. Miranda stays on.

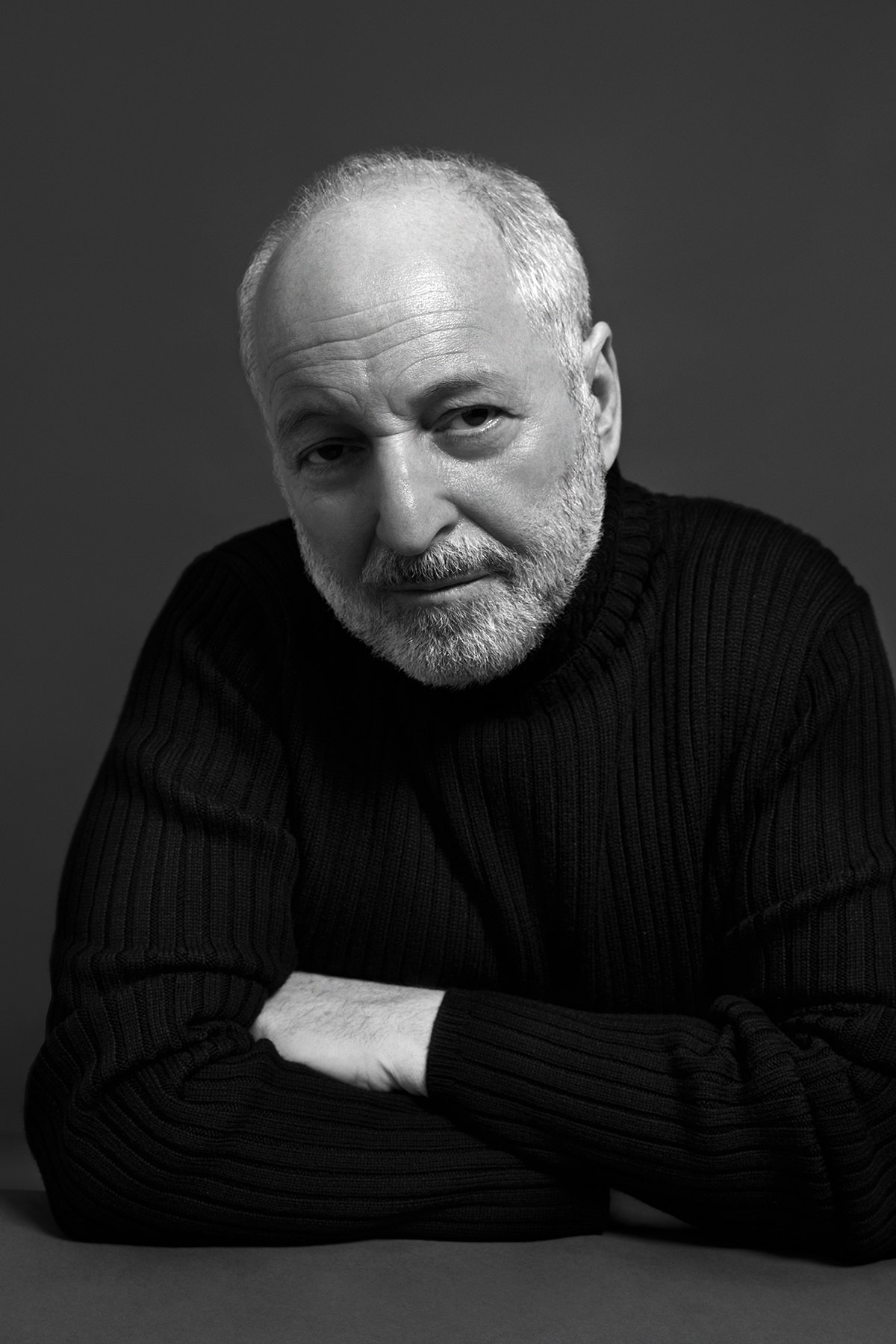

In person, Aciman speaks like the dialogue in Find Me, rhythmic and philosophizing. We sit in the living room of the apartment he shares with his wife of nearly 32 years, where they raised their three sons. As we face each other on identical beige couches, he barely pauses after questions before delivering long, eloquent answers in his unplaceable accent. (Aciman spent his childhood speaking French in Alexandria, Egypt.) Soon he grows passionate, waving his arms. When emphasizing, his eyebrows arch into crescents as if shielding his face from a torrent of thoughts.

Growing up, Aciman developed the worldly existence he would come to show through his characters, moving from Egypt to Italy to France to the U.S., all by the time he was 17. When he was 14, his Jewish family was kicked out of largely Muslim Alexandria after their business was nationalized and their assets were seized. They were left with nothing as refugees and spent three years in Rome before finding their way to New York to rebuild in 1968.

Aciman studied as an undergrad at New York’s Lehman College, then dabbled professionally as a broker and in advertising before becoming a professor. “I’m trying to get rid of everything so I can do the one thing I’ve always cared to do,” he remembers thinking, “which is to be a writer.” He chronicled much of his youth in his first book, the 1994 literary memoir Out of Egypt. In addition to his memoir and novels, Aciman has written multiple essay collections and edited one about Proust.

Guadagnino, the Call Me by Your Name director, recalls Aciman speaking to him in “beautiful Italian” over breakfast in New York when they met for the first time to discuss the movie. The director says Aciman allowed him and his crew freedom with the source material. Guadagnino has discussed wanting to make a sequel to Call Me by Your Name and has spoken publicly about prominently featuring the AIDS crisis in the version he is writing, but he says he hopes to meet with Aciman in New York and discuss combining their visions. Aciman is “generous,” Guadagnino says, and “does not perceive everything from the perspective of his own art.”

But to hear Aciman tell it in a word, he’s “weird.” He is certainly unpredictable. He writes wise books about the nature of love and time and the inter-actions of those forces, and yet he claims to think like a 14-year-old. (He’s 68.) His books endlessly pour out ways to say, “I love you,” without saying, “I love you.” He denies being a romantic but concedes that is he perhaps a “romantic — with a sense of irony.” His medium is literature, yet he believes classical music is the “topmost layer of aesthetic production of mankind.” Find Me’s four chapters are named after musical terms (“Tempo,” “Cadenza,” “Capriccio” and “Da Capo”). Invoking the art form he finds superior is, he says, his way of saying, “O.K., guys, if I’m not perfect, at least I know what is.”

Aciman’s living room is lined with seascape paintings of varying abstraction. He doesn’t like details, he says, which sounds like a contradiction from a writer with such precision. But it’s the mundane, granular details he dislikes. Aciman writes in the tradition of roman d’analyse or, as he frames it, the focus on what motivates people to speak, feel or behave the way they do. “I’m only interested in what two people or three people will do when they’re sitting down and chatting together,” he says, from the facing couch. “That really is what fascinates me.”

Though he is “quite straight,” Aciman says life taught him what it is to be “totally fluid.” That, along with imagination, is what he says allowed him to write such a convincing same-sex love story — a question about identity that is often asked when it comes to this book. Writing the explicit man-on-man sex in Call Me by Your Name, Aciman says, took no particular courage. “I just wrote it,” he says, shrugging. Still, he acknowledges there’s an irony that he, the straight guy, wrote gay sex that was toned down considerably in the film by Guadagnino, who is gay. That was one of the chief criticisms of the adaptation — that scenes like the one in which Oliver eats a peach that Elio has used for a sex act were restrained in the movie.

“I got a lot of mail of people saying, ‘Why doesn’t he eat the peach? We wanted to see that,'” Aciman says. “I understand.” Even so, he was pleased with the film and admits he’s not a big fan of watching sex scenes himself. He chalks up any cinematic chastity to “compromises” standard in the film industry.

As in Call Me by Your Name, the settings in Find Me are idyllic — the novel takes us through Rome, Paris, New York and back to the Italian countryside. His characters are secure financially and unburdened by the bigotry that in other stories threatens queer love. The turbulence, in Aciman’s world, calls from inside the house.

“My belief is that whenever you go into somebody’s head — anyone’s head — it’s all insecurity,” he says. “It’s all doubt, it’s all reluctance, it’s all inhibition, shame, that’s all it is. There are sparks of desire that keep us interested in real life, but ultimately there’s something suffocating all of us.” That sense of instability and insecurity has an obvious root in his life story, and it finds its way into the lives of his characters, unlucky lovers included. “I live with that fear that in a minute,” he says, “everything could go away.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com