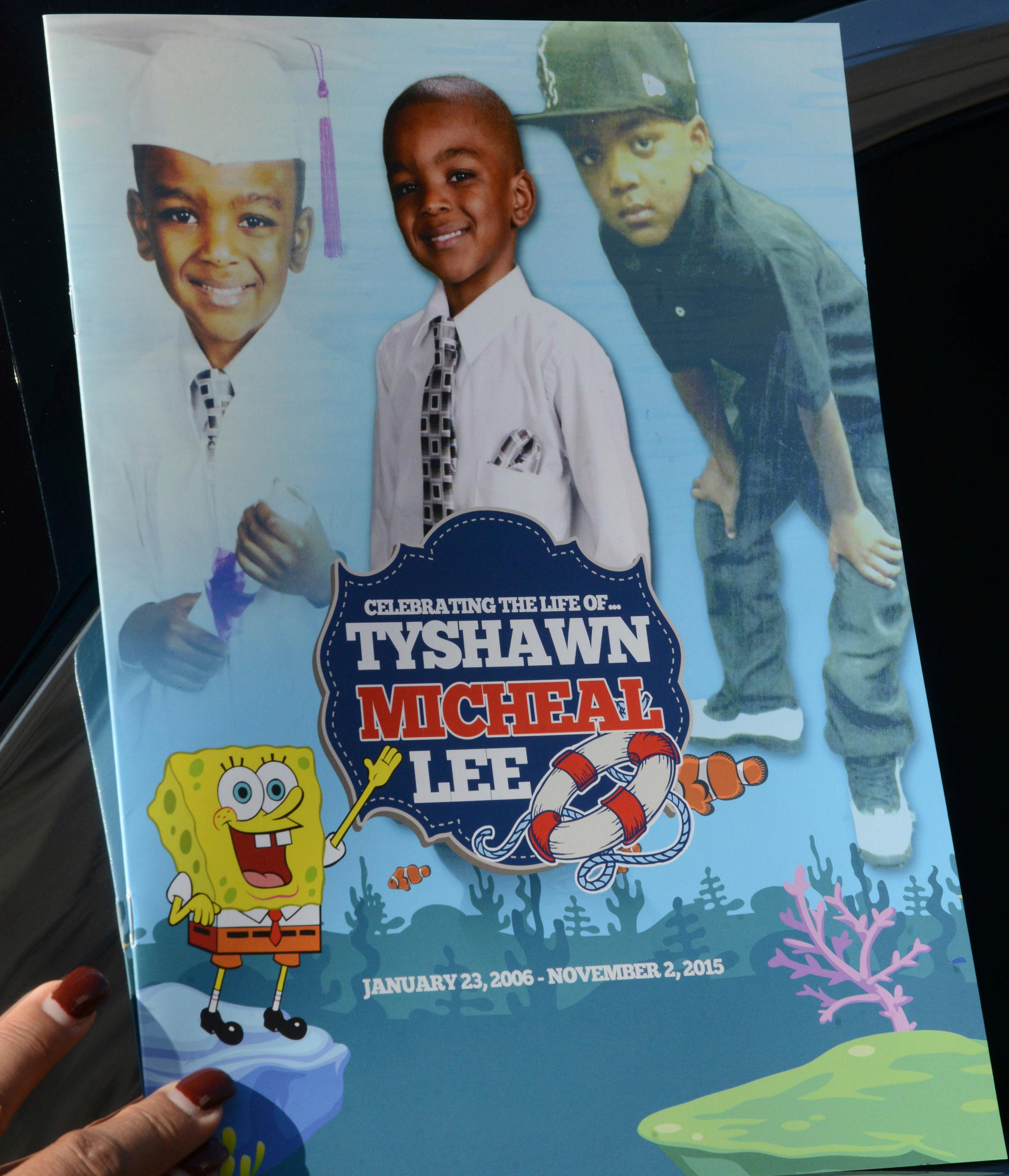

At the conclusion of a nearly three week-long trial in Chicago, jurors have found two men guilty of the 2015 murder of 9-year-old Tyshawn Lee. Described by community members as an “inhumane” crime, and a case that drew the national spotlight, it was alleged the one defendant on trial shot and killed Tyshawn in a gang-related execution, at the other’s behest.

During the trial, prosecutors said Tyshawn was playing on a basketball court in a South Side Chicago park when Dwright Boone-Doty, 25, tricked him into going into an alley, at which point he shot the child multiple times. This was allegedly at the behest of fellow defendant Corey Morgan, 30, prosecutors claim. A third man, Kevin Edwards, who has already been convicted and sentenced, acted as a getaway driver and lookout.

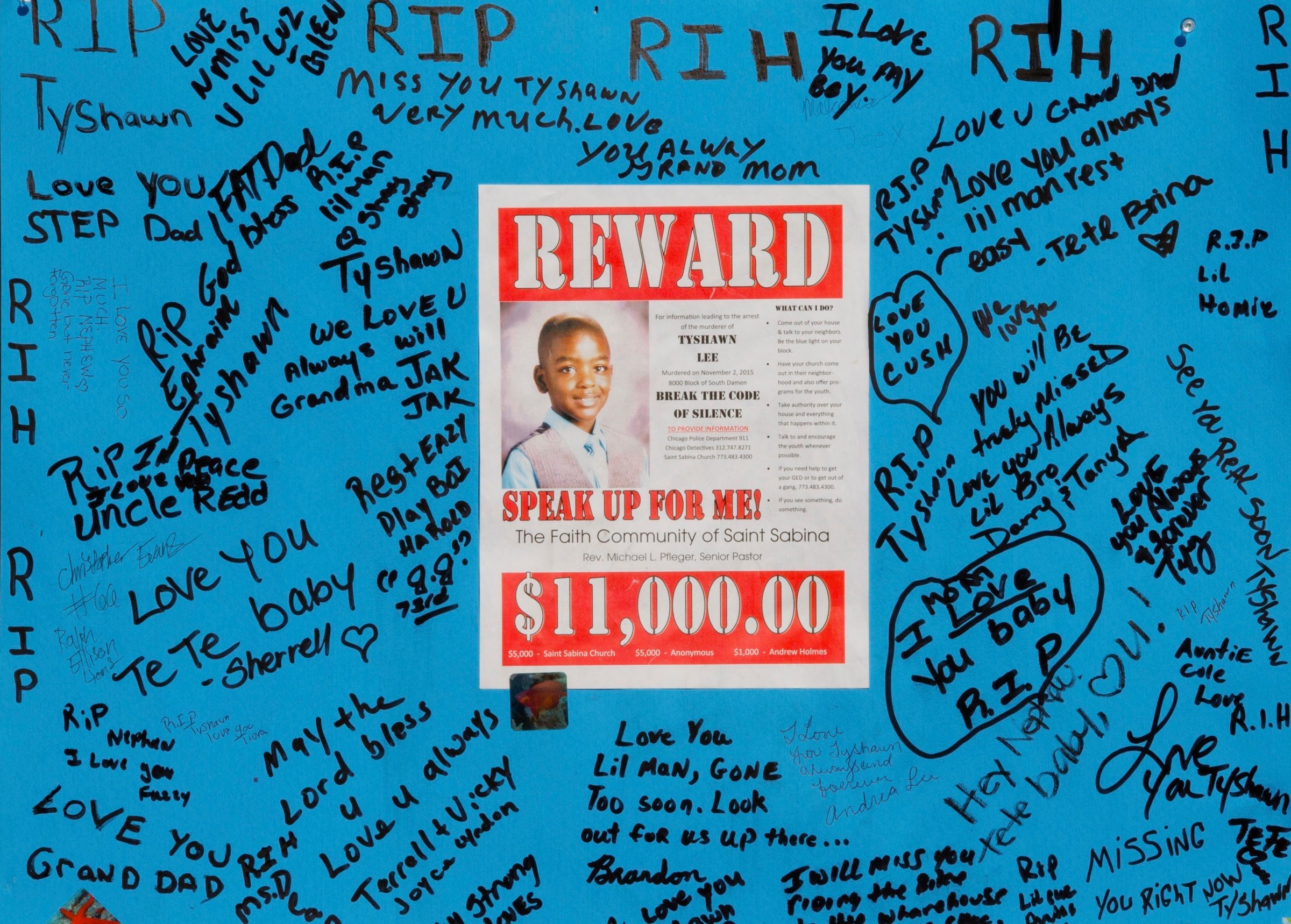

“A child in a casket to me is the face of evil, but this was a whole new level,” Reverend Michael Pfleger, who gave the eulogy at Tyshawn’s funeral, tells TIME.

A Cook County jury deliberated for just over two hours on Oct. 3 and found Boone-Doty guilty of first-degree murder. A second jury found Morgan guilty of the same charge on Oct. 4.

Prosecutors claimed the defendants believed that Tyshawn’s father, Pierre Stokes, was a member of a rival gang, and that he was responsible for a previous shooting in which Morgan’s brother Tracey was killed and his mother was wounded. Stokes has not been charged in relation to that shooting; Khalil Yameen and Christopher Smith — alleged members of the same gang that police have also claimed Stokes was involved with — were later arrested.

Both Yameen and Smith were charged with first-degree murder and attempted first-degree murder in October 2016. They are still awaiting trial, according to authorities.

Stokes has never confirmed any gang affiliation — in a 2015 interview with the Chicago Tribune, he “did not talk specifically about whether he was a gang member,” and added that he did not feel the narrative that the police had painted about him was not accurate. He said that no one should have had a motive to kill his son.

Morgan and Boone-Doty’s trial began on Sept. 17. Here is everything you need to know about the crime, and the ensuing court proceedings.

What happened to Tyshawn Lee?

On Nov. 2nd, Tyshawn was playing in Dawes Park, a public park on the south side of Chicago, after school with other kids. He was approached by Boone-Doty and Morgan, who began playing basketball with him to gain his trust, Assistant State Attorney Margaret Hillmann said at the trial.

Boone-Doty then allegedly picked up Tyshawn’s basketball, offered him a juice box and led him to a nearby alley, while Morgan and Edwards watched from a nearby parked car.

“And Dwright Doty took out a .40-caliber handgun, and he executed Tyshawn in broad daylight,” Hillmann told jurors in her opening statement at the trial.

“Tyshawn Lee was murdered in probably the most abhorrent, cowardly, unfathomable crime that I’ve witnessed in 35 years of policing,” then-Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy told reporters in 2015.

Who was arrested for Tyshawn’s murder?

Morgan was arrested three weeks after the shooting on Nov. 25th and subsequently charged with Tyshawn’s murder. Boone-Doty was arrested on the same charge in March 2016.

The third man, Edwards, pleaded guilty to a first-degree murder charge in September and received a 25-year prison sentence. He did not testify against Boone-Doty or Morgan.

The shooting of Morgan’s mother broke a ‘gang code’ mandating that innocent family members be left out of gang disputes, prosecutors argued to the jury. (According to Hillmann, Boone-Doty and Morgan are allegedly members of the Black P. Stone Nation Bang Bang Gang (BBGs). Stokes is allegedly part of the Gangster Disciples Killa Ward gang.) With that ‘code’ broken, prosecutors claim Morgan arranged for Stokes’ family to be targeted in revenge.

Police say that, in 2016, on the same day that Boone-Doty first appeared in court over Tyshawn’s murder, Stokes was involved in a “gang-related” shooting. He is currently in jail awaiting trial for aggravated battery and other charges related to the attack, in which three men were wounded.

Stokes “suffered an unspeakable loss with the calculated execution of his son,” Chicago police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi at the time of his arrest, according to the AP. “Despite this, he continued to engage in the same gang activity that started this initial cycle of violence.”

What happened during the trial?

During opening statements on Sept. 17, Hillmann explained the prosecution’s case in emotive detail to the jury, telling them that Tyshawn was so excited to play basketball after school that he hadn’t even changed out of his uniform.

“Tyshawn brought a basketball to Dawes Park. Corey Morgan, Dwright Doty and Kevin Edwards brought guns,” she said.

Hillmann said that Boone-Doty’s DNA was found on the basketball found next to Tyshawn’s body, and that the two men were seen with the victim before the shooting happened. Although prosecutors did not argue Morgan shot Tyshawn, they alleged he orchestrated the murder as a revenge attack — and was thus also culpable. (Prosecutors also claimed Morgan gave Boone-Doty the gun used in the murder.)

To this effect, several witnesses testified to seeing Boone-Doty and Morgan in Dawes Park. One witness also told the court he saw one of the defendants with a gun, according to ABC7 Chicago.

Thomas Breen, an attorney for Morgan, told the jury that Boone-Doty acted on his own. In his opening statement, he argued that Morgan had nothing to do with the crime. “That execution of that 9-year-old boy has to come from one singularly evil person,” Breen said to jurors. “Not from a plan. His killer did so of his own volition and for his own reason. Not at the behest or help of Corey Morgan.”

A second attorney for Morgan said that the prosecution failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Morgan orchestrated the murder, while Breen instructed the jury to look for the “lies” he claimed were contained in the case against his client.

Brett Gallagher, an attorney for Boone-Doty, also told the jury to be “skeptical” about the state’s case in her opening statement. She in turn claimed that Morgan is the defendant with a potential motive in the killing, not Boone-Doty.

Boone-Doty’s defense team later argued that no one saw him kill Tyshawn and that police felt pressured to make an arrest.

Gallagher also addressed audio recordings of Boone-Doty discussing his involvement in the murders while in jail awaiting the trial — and argued that he only spoke about the murders to appear tougher to other inmates. (Jurors heard the 2015 recording, in which Boone-Doty told an informant in jail that he killed Lee, and even laughed about the murder.) “He pretended to be bigger and badder and more ruthless than he actually was in order to survive,” Gallagher told the jury.

Neither Gallagher nor Breen addressed their clients’ explanation of the circumstances surrounding Tyshawn’s death during the trial. Neither attorney responded to TIME’s request for comment on this matter, or with regards to their clients’ potential affiliation with gangs.

On Sept. 18, Tyshawn’s grandmother, Bertha Lee, took the stand. She told jurors that the last thing Tyshawn said to her was that he loved her, according to the AP.

During closing arguments, the prosecution showed the jury photos of Tyshawn after he was shot, as well as autopsy photos of his body.

How has the Chicago community responded?

Community members and activists say that this murder hit residents harder than other instances of gang violence, which has long plagued the city.

As the crime’s details began to emerge, “people just got more and more angry,” Reverend Pfleger says. But he notes that the emotional impact of such violence is, at least, two-fold. “It causes people to live in fear,” he adds.

“We want to get children out of the house… we want them to go out and get exercise, but you can’t do that if you live in a place where you’re afraid your child is going to get shot and killed,” Pfleger says.

Tyshawn’s killing came during a year in which 468 people were murdered in Chicago. 2016 saw a significant jump in murders still, with 769 people killed, according to the Chicago Police Department.

Cinaiya Stubbs, the Executive Director of Chicago Youth Programs, a youth organization that serves a variety of neighborhoods in the city, says the effects of gun violence are amplified by the fact that they are often concentrated on specific neighborhoods. She feels this leaves residents desensitized, and in some cases indifferent to the violence.

Stubbs also believes a much larger cultural desensitization is at play in how the greater general public responds to such horrifying crimes — and that national attention is often fleeting. “It takes something that the external community sees as vile for people to stand up and pay attention,” Stubbs tells TIME of Tyshawn’s murder. “[But] something that we’ve learned is that they may look for 30 seconds… and then people will go back to their regular business.”

Adam Alonzo, the CEO of Build Chicago, another organization that aims to help children in the city, agrees that the shooting was “shocking” and “tragic.” But he also says more attention needs to be on people in the impacted neighborhoods who are trying to make a difference.

“We can focus on what is completely wrong in these situations or think about how we highlight the work of folks who are out there really trying to do this work to engage the community,” Alonzo tells TIME. “If you let the reality of some of these things sink in and that then takes root and you let it grow, it takes over and you can’t see anything positive. Those are things we do not want our kids to hold as their truth.”

What happens next?

Boone-Doty and Morgan face a minimum of 20 years in prison — and up to a maximum charge of 60 years. Tyshawn’s grandmother told reporters she wants to see the men get the maximum sentence.

Beyond their sentencing and the focus on punitive justice, activists say changes in impacted communities will require a larger, more sustained effort from neighborhood residents along with the local and federal government.

“The systemic part of [combatting gun violence] would require a complete and utter strip-down of how things are done so inequitably,” Stubbs says. “Internally there are stigmas that exist that we have perpetuated that would have to also be stripped down. There is no quick and easy answer to these problems.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com