It has been 79 days since an estimated one million people took to the streets of Hong Kong to join a protest that kicked off a summer of upheaval, and the movement shows little sign of abating. The protests that gripped this semiautonomous region of China beginning on June 9 have become its longest period of unrest since the former British colony was returned to Chinese sovereignty in 1997.

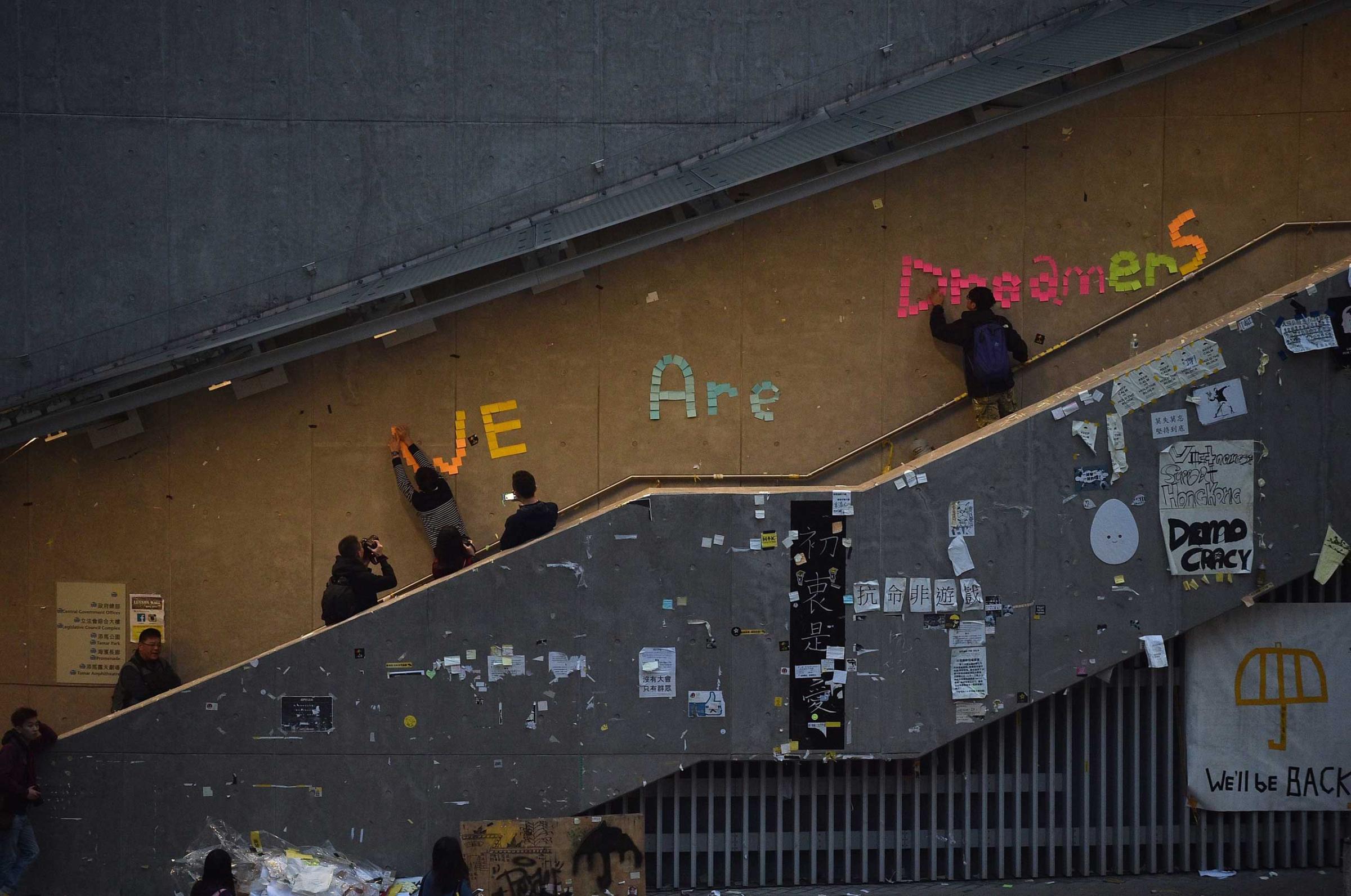

The current series of protests have now outlasted the Umbrella Movement of 2014, when pro-democracy demonstrators occupied part of the city’s busy financial district, camping out in colorful tents until public support petered out and police cleared the sites. The earlier movement, which demanded free elections of the city’s leader, ended without concessions and was viewed by many as a failure. But five years later, protesters say they are putting hard-learned lessons into practice toward a more sustainable approach to their activism.

Indeed, the current protests have proven difficult for the government to control. What began as a march against an unpopular extradition bill, now suspended, soon snowballed into a broader movement demanding greater democratic freedoms. Instead of occupying a finite space at the city’s central core, protesters have adopted a strategy based on the concept “be water,” borrowed from martial artist and Cantonese movie legend Bruce Lee. The protests are marked by their fluidity, taking form as “pop-up” events all over the city without lingering too long in a single location. They’re largely unpredictable, often planned in real-time via encrypted social media apps. And this time around, the movement has no clear leadership, making it impossible for authorities to identify and arrest its would-be masterminds. “It’s hard to break down our movement,” says Natalie Lee, a 24-year-old protestor. “You can target an organization, but you can’t target mass citizens.”

Strategy isn’t the only difference between then and now. Both authorities and protesters have become much more willing to escalate their tactics, resulting in scenes of violence that seemed unimaginable five years ago. While the demonstrations have by-and-large been peaceful, confrontations between police and protesters have further inflamed tensions; one of the movement’s key demands is an independent inquiry into allegations of excessive force used by officers. Tear gas and rubber bullets, which were rarely used before, are now a normal part of the news cycle. A small faction of the protesters have taken more radical action such as attacking police, hurling bricks and homemade smoke bombs toward them and vandalizing government property. Sunday marked a major escalation, as an officer discharged a live round as a warning shot after being assaulted by protesters.

Protestors say they are more desperate now after their battle five years ago achieved little. Jackie S., 23, tells TIME he has been on the frontlines during a number of stand-offs with police. “Back in 2014, I never imagined that I’d be like this,” he says, “learning how to remove metal barricades from the streets, how to put out tear gas right after it’s fired.” As Jason Buhi, a China expert who teaches law at Barry University in Orlando, Fla., observed, the protesters are “willing to get their hands dirty” this time around. “They’re willing to do what it takes in a way that wasn’t on their minds in 2014,” he says.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

Beijing continues to push the narrative that foreign governments are behind the unrest. Chinese state media has branded the movement as a “color revolution,” a reference to anti-authoritiarian protests that swept former Soviet states in the early 200s. And as tensions escalate, fears mount that Beijing could intervene; paramilitary police have reportedly amassed in the neighboring city of Shenzhen in recent weeks, while the People’s Liberation Army maintains a permanent troop presence in Hong Kong. As dramatic as the events of 2014 were, the possibility of Chinese armed intervention has never seemed as real as it does now.

Read more: A Brief History of Protest in Post-Handover Hong Kong

But the differences seen on the streets today reflect how little progress has been made since the Umbrella Movement of 2014. Instead of seeing democratic change, Hong Kongers say they’ve witnessed a steady erosion of civil liberties. Fears about growing Chinese encroachment in the territory’s affairs have been underscored by a series of alarming developments, such as the 2015 disappearance of five booksellers known for peddling salacious texts about the Chinese Communist Party, and later the arrest of several activists associated with the Umbrella protests. “The whole world is moving forward, why do we have to move back?” asks a 20-year-old protestor who goes by the nickname Sylvia.

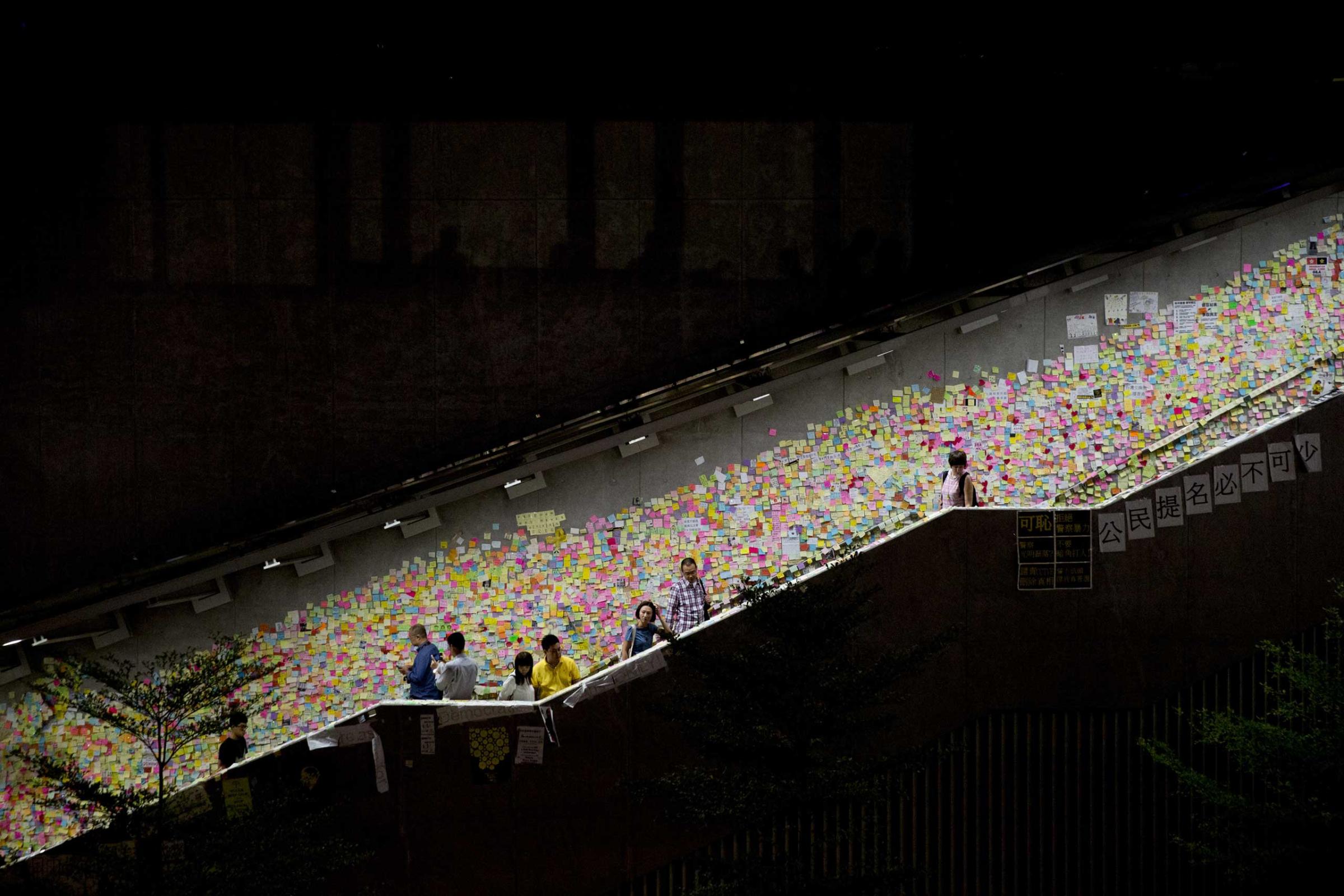

In other ways, Sylvia says, little has changed since she and her classmates would rush to join the protests after school. Just like in 2014, protest art is plastered on walls and along the bridges connecting the city’s maze of skyscrapers. Despite pockets of chaotic confrontation, the protestors are still, on the whole, lauded for their civility; offering food, water and first aid to fellow demonstrators. Many return the day after a protests to pick up trash to leave public sites clean and orderly.

Perhaps the clearest constant between then and now is the persistence of the public in the face of an unresponsive government. “They don’t think they’re going to really get what they ask for, but the belief is that if they don’t keep fighting, that will really be the end of Hong Kong,” says Victoria Tin-bor Hui, an associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame. “They cannot afford to lose, to just go home this time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Hillary Leung / Hong Kong at hillary.leung@time.com