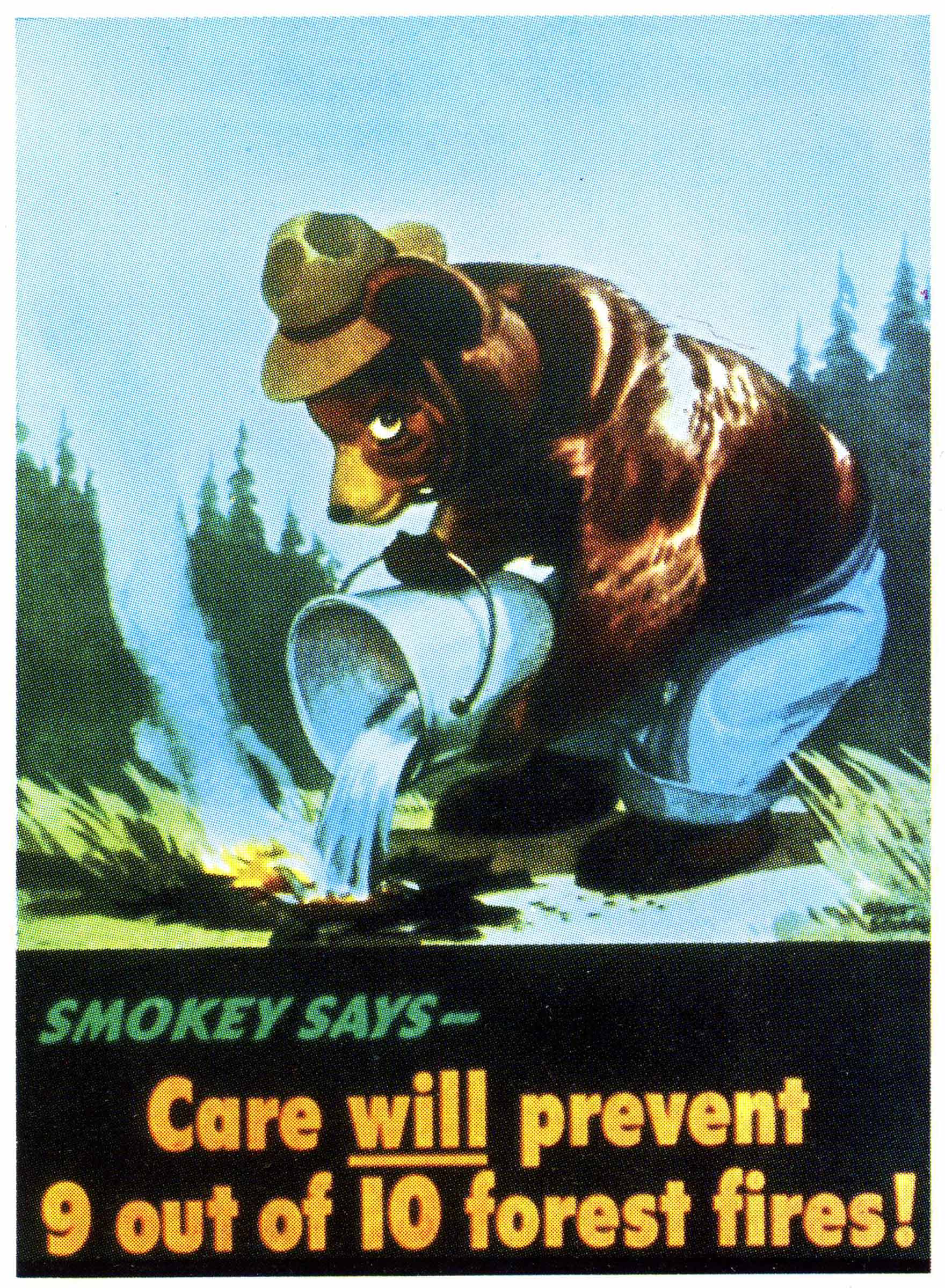

Friday marks a big birthday for Smokey Bear. The grizzly face of fire prevention was introduced on Aug. 9, 1944 — 75 years ago — by the U.S. Forest Service and the Ad Council, then called the War Advertising Council. His first poster, designed by artist Albert Staehle and captioned “Care will prevent 9 out of 10 fires,” shows Smokey Bear putting out a campfire by pouring a bucket of water over it.

The charming cartoon bear had a serious message. The character famous for fighting forest fires was invented just as the U.S. was fighting World War II, and the heightened fear of wildfires coincided with a heightened fear of enemy invasion.

On Feb. 23, 1942, just about three months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, a Japanese submarine started firing shells at the Ellwood oil fields near Santa Barbara, Calif. The attack didn’t do much damage that day, in the sense that the shelling wrecked a derrick and a pump house and didn’t kill anyone, but it did cause a lot of damage later, sparking fears that the Japanese were getting ready to invade. The front page of the Feb. 24 Santa Barbara New-Press declared that the shelling was the “First Attack Of War on Continental U.S.”

The attack is considered one of the key incidents that convinced the U.S. to relocate Japanese-Americans into incarceration and internment camps, which the government years later admitted had been “a wrong” for which “no payment can make up.” Los Angeles-area military units were on high alert. On Feb. 25, troops beamed up searchlights so they could be on the lookout for enemy planes; thinking they saw some, they fired anti-aircraft shrapnel over Santa Monica Bay. The sightings were all false alarms, and the artillery in fact damaged people’s homes. Five deaths are thought to have resulted from heart attacks and car accidents during the incident that became known as the “Battle of Los Angeles.”

And just beyond the Ellwood oil fields was the Los Padres National Forest. If future shelling attacks hit the trees, a wildfire would start.

“It became apparent to the public that we needed to protect America’s natural resources,” Gwen Beavans, the National Wildfire Prevention Branch Chief at the USDA Forest Service, tells TIME. “If we didn’t have our trees, we wouldn’t be able to support the war effort.” Not to mention that manpower to fight fires was short, given that some of the nation’s most experienced firefighters had been drafted. And as blackouts were implemented to prevent showing coastal targets to Japanese submarines, people were also afraid that wildfires would help enemy subs see the land better.

Teams at the National Association of State Foresters and the War Advertising Council started to put their heads together to tackle the problem. Early forest-fire prevention slogans were more directly war-related, including “Forest Fires Aid the Enemy: Use an ash tray” and “Our Carelessness: Their Secret Weapon: Prevent Forest Fires” and featuring racist caricatures of Imperial Japanese Army General Hideki Tojo.

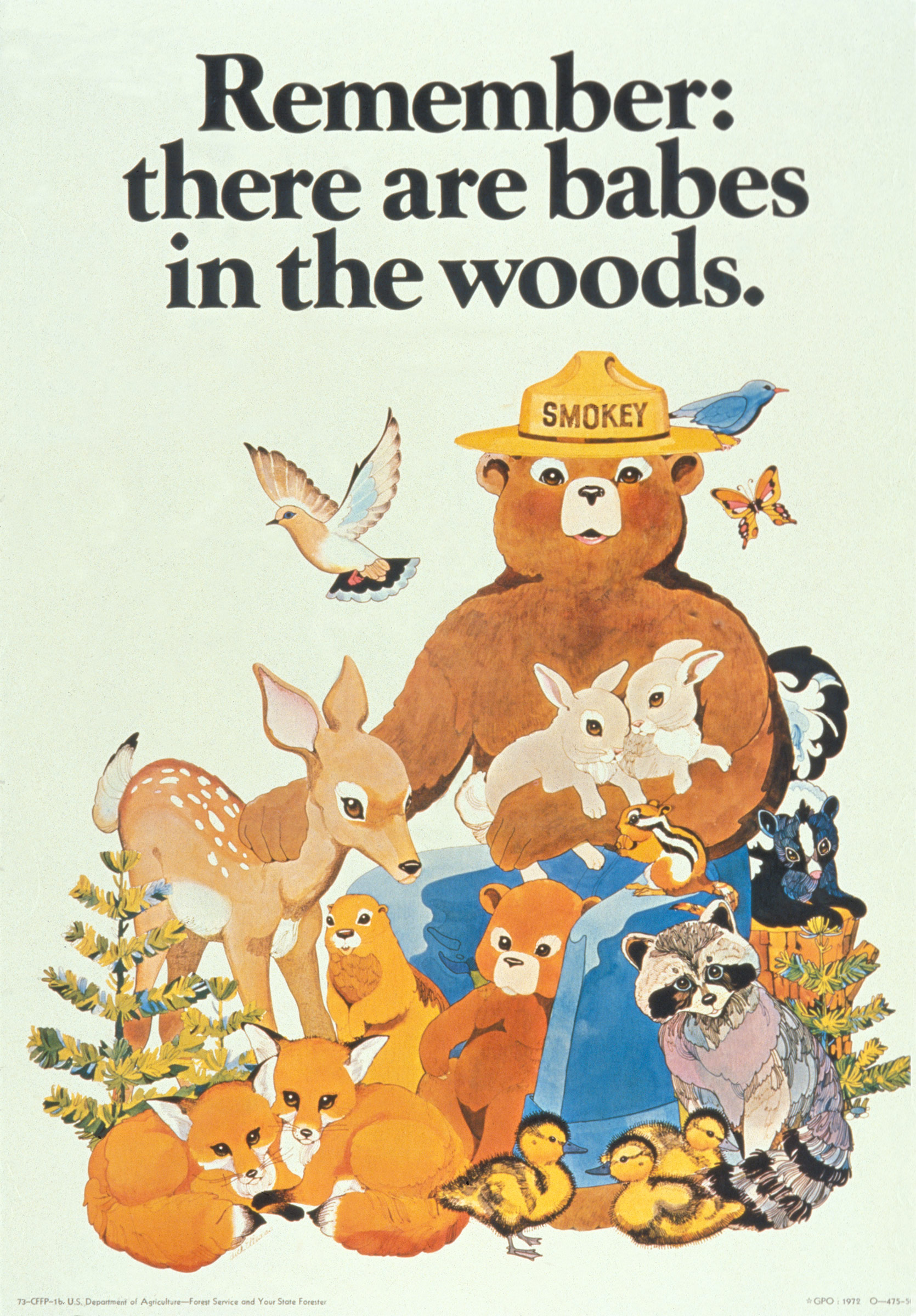

But in August of 1942, new inspiration arrived in a surprising place: Bambi came out. The movie became an instant hit. Disney let the forest agency borrow their forest-dwelling star for a year, but Bambi’s campaign was so successful that the agency realized it needed to create a permanent friendly animal face for the cause.

Enter Smokey.

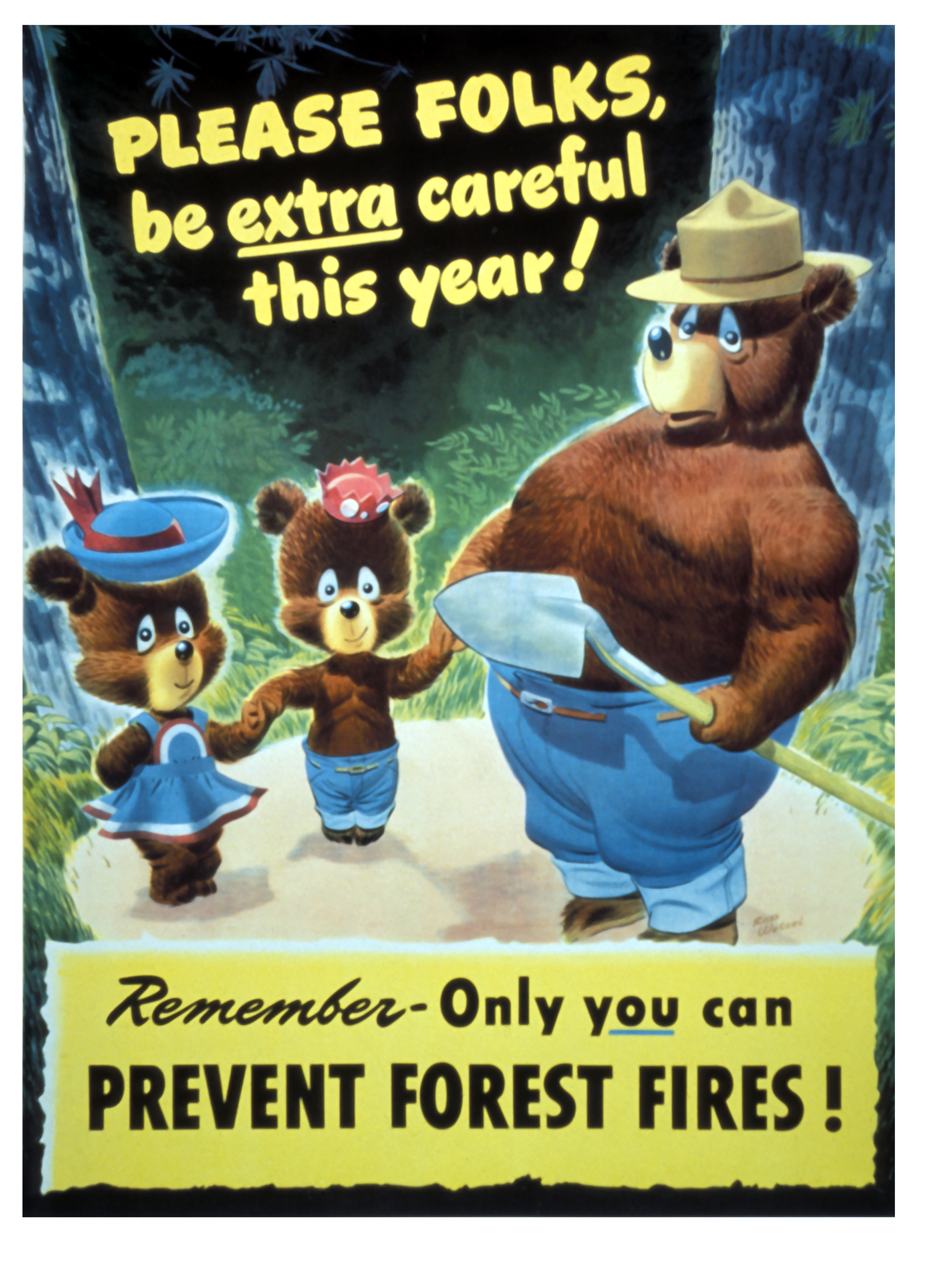

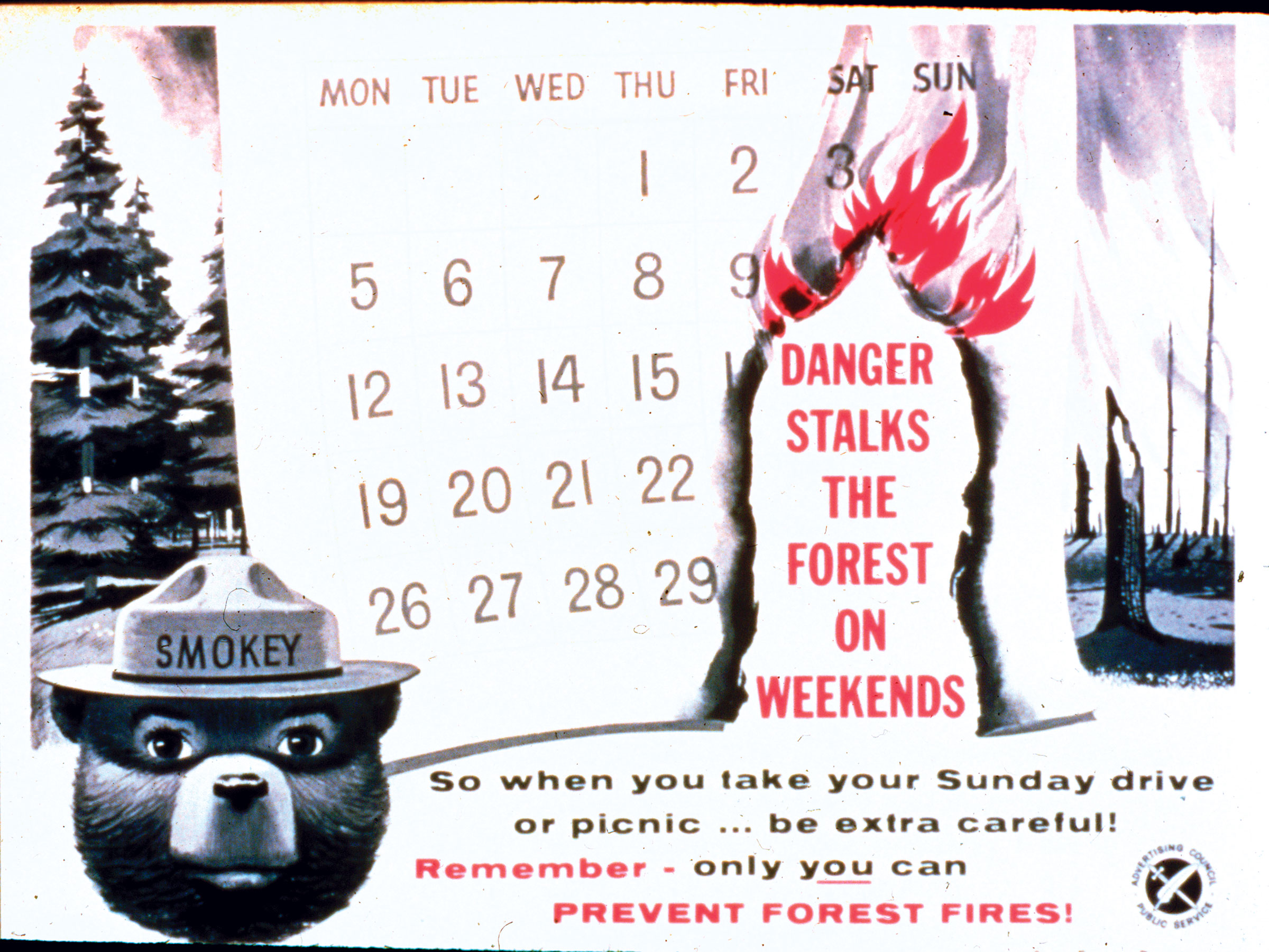

And Smokey Bear — whose most famous line, “Only you can prevent wildfires!” first appeared in 1947 — became even more popular after the war. As more Americans drove to the great outdoors, fueled by the post-war economic boom, the risk of campfire disasters increased. In fact, a real bear helped the cartoon bear become a household name. In the spring of 1950, firefighters rescued a scared black bear cub from Lincoln National Forest while battling a blaze at New Mexico’s Capitan mountains. Game officer Ray “Ranger Ray” Bell took it to a veterinarian and dubbed it Smokey because it looked like the bear in the forest fire prevention ads. The cuddly bear got a lot of press attention, and was flown out to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., to be the official symbol of fire prevention. Country music singer Eddy Arnold’s 1952 song about “Smokey the Bear” helped cement that name for the bear in people’s heads.

As the above selection of Smokey posters shows, Smokey Bear’s appearance has changed throughout the years. But his message has stayed pretty much the same.

His message did evolve to reflect the latest forest fire prevention safety techniques over the last 75 years. While the 1944 poster showed Smokey Bear pouring water over a fire, today, Smokey Bear does more than that. He demonstrates the “drown, stir, & feel” method of putting out campfires, showing campers how to pour water over the site, stir the hot coals and dirt, and then pour more water on that black soupy mixture. If it feels hot when campers place the back of a hand above the coals, the process needs to be repeated until it no longer feels hot above the coals.

We may not know how much of the 60% decrease in forest fires since the 1940s can be attributed to Smokey Bear’s popularity, but one thing hasn’t changed in terms of forest-fire prevention techniques in 75 years. As as 1944 ad pointed out, nine out of ten of them are caused by humans.

Correction, Aug. 9

The original version of this story misstated the day of the week Smokey Bear’s birthday falls on this year. It is on a Friday, not a Saturday.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com