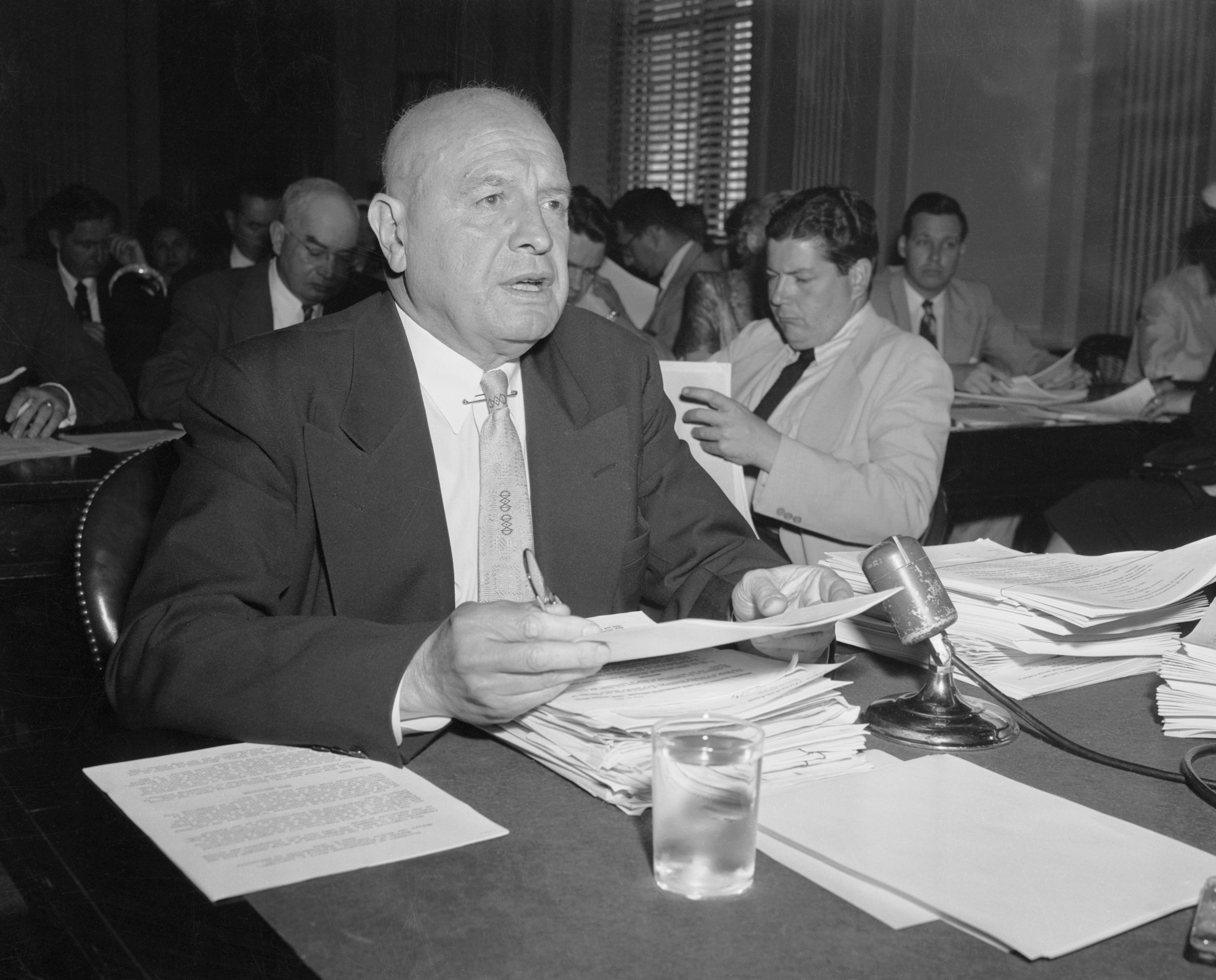

When Prohibition ended in 1933, drug enforcers finally had a new agency they could call their own, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. This launched the career of its first commissioner, Harry Anslinger, the person most synonymous with the phrase “war on drugs”—in fact, the first person to use it—and likely the first person, outside of any royal family, to be referred to as a “czar.”

Between 1930 and 1962, Anslinger established the standards that continue to serve as basic tools of the trade for America’s drug enforcement, such as dramatic drug busts, harsh penalties and questionable data. There remains serious disagreement in scholarly as well as political circles about how successful Anslinger really was in reducing drug sales and use in America, though he achieved several significant legislative victories, including the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act, which fostered collaboration between federal agents and police in different states (each of which had its own specific laws).

But, as difficult as passing drug laws is, enforcing them effectively, consistently and fairly has proven to be virtually impossible.

Anslinger unapologetically divided the world into us and them, good and bad, right and wrong—and always black and white. While Anslinger’s 30-year war on drugs undoubtedly saved the lives of some individuals, his racial prejudices tarnished his reputation in ways that, even allowing for 20/20 hindsight, can’t be dismissed. The most blatant example was his disparate treatment of two of the nation’s most famous celebrities in the 1950s: Judy Garland and Billie Holiday.

Anslinger didn’t like stars. Still, he treated Judy Garland with kid gloves. The star of The Wizard of Oz suffered from an eating disorder before the phrase was coined. Determined to make sure she lost her baby fat as she evolved from brick roads to adult roles, her studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Garland engaged in what she called a “constant struggle . . . whether or not to eat, how much to eat, what to eat. I remember this more vividly than anything else about my childhood.” In this, MGM had a trusted ally in the star’s mom, Ethel, who had already been giving her daughter pills to in the morning to wake up and at night to go to sleep. “Now,” as one biographer put it, “Metro added diet pills, combinations of Benzedrine and phenobarbital, to that already potent mixture. The studio had found the ultimate weapon.” It was a weapon that worked not only to keep her weight off but also allowed her to stay “vivacious before the camera during the long shoot days.”

Soon she began to demonstrate the kind of unreliability—in terms of when she’d show up on set and what condition she’d be in—that Marilyn Monroe became famous for.

With informants planted all over Hollywood, Anslinger knew what drugs Garland was doing and where she was getting them, so one day he intervened by visiting the heads of MGM and insisting they send her to a sanatorium, saying, “I believed her to be a fine woman caught in a situation that could only destroy her.” He was told they had $14 million invested in her and had no intention of giving her the time off she needed. An unsuccessful suicide attempt—even if only a cry for help—finally persuaded them that the best way to protect their investment was to send her to rehab. Later, Anslinger would imply that he had played the major role in helping Garland get clean, but that may also have been just a story only he believed.

Anslinger’s reaction was exactly the opposite when he heard about a black woman singing about strange fruit hanging from poplar trees: “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.” For him, Billie Holiday was an ideal symptom of the drug problem—and an irresistible target for his crusade. She was a woman. She was black. As a child, she scrubbed floors in a brothel. She was 11 when someone first tried to rape her. She made $5/client when she was pimped out at 14. She sang jazz—an improvised, undisciplined, free-form music with Caribbean and African influences that Anslinger referred to as sounding “like jungles in the dead of night.” To make things even worse, she flaunted how much she drank and the drugs she took.

The brilliant scholar and 1960s cultural icon Angela Davis makes the point that most common portraits of Billie Holiday “highlight drug addiction, alcoholism, feminine weakness, depression, lack of formal education, and other difficulties unrelated to her contribution as an artist.” Indeed, most creatives—writers, artists, musicians, actors, et cetera—are known first for their works. Their biography serves as background. With Billie—as with other celebrities who have dealt with addiction—it’s often the other way around. Emphasizing Holiday’s drug use enabled Anslinger to minimize her influence on the arts, social consciousness and the growing civil rights movement—a way to keep the focus on her color not her creativity, on her addictions not her artistry.

When, by June 1959, Holiday was in New York’s Metropolitan Hospital on her deathbed, weakened by liver and heart disease, Anslinger ordered agents from his Federal Bureau of Narcotics to storm into her room and arrest her for drug possession. They handcuffed her and put her under a police guard until a judge ordered the cuffs removed.

Whenever she performed the song “Strange Fruit,” she had the lights turned down. And when they came back on, she was gone. Billie Holiday died in that locked hospital room on July 17, 1959, at age 44.

Harry Anslinger died on Nov. 14, 1975. He was 83 years old and suffered from an enlarged prostate and angina. At the end of his life, Anslinger took morphine for the pain.

Excerpted from the book Opium: How an Ancient Flower Shaped and Poisoned Our World by John H. Halpern and David Blistein, to be published on August 13, 2019 by Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2019 John Halpern and David Blistein.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com