Ross Perot, the self-made Texas billionaire and one of the most successful third-party presidential candidates in U.S. history, died on Tuesday, his family’s spokesperson confirmed. He was 89.

Running as an Independent in the 1992 presidential election, he lost to Bill Clinton, but captured 19% of the vote. He was famous for uniting “both socially conservative, blue-collar, anti-NAFTA voters with fiscally conservative but socially moderate voters,” who wanted a change from the status quo, didn’t trust established political parties and who wanted to reduce the outsize power that lobbyists and special interest groups exert over policy decisions. And significantly, Perot was one of the first candidates in the modern era to attempt to bring his political message directly to the American public using the growing media landscape.

It all started when he announced his willingness to run for president on Larry King Live on Feb. 20, 1992, if the American people got him registered on 50 state ballots. TIME’s May 25, 1992, cover story called these citizen drives “the largest outpouring of volunteer enthusiasm America has seen since yellow ribbons dangled from every lamppost during the Gulf War…No independent candidate in 80 years has attracted anything like this kind of support.”

The magazine called his campaign “both a symptom of the failure of American democracy and a hopeful beacon of its ability to regenerate itself,” lamenting the professionalization of presidential politics. “Ross Perot in three short months has out of nothing created something far larger than a multibillion-dollar company, or perhaps something even larger than the multimillion-dollar campaign he will fund. Win or lose, his populist crusade and the challenge he is mounting to the establishment parties may well help break the deadlock of American democracy.”

In a Q&A in that same issue, Perot argued that the popularity of his campaign spoke to a larger untapped feeling of voter discontent: “What is happening has nothing to do with me. It has everything to do with people’s concerns about where the country is and where the country is going. There is a deep concern out there about the kind of country our children will live in that I don’t believe has surfaced in the polls yet. And if I want 100,000 volunteers more, all I need to do is go on some national show.”

That summer, commentator Charles Krauthammer further analyzed Perot’s media strategy and how his campaign was disruptive, not only in terms of what kind of voters he was appealing to, but also in terms of how he was appealing to them. Here’s how he described the phenomenon in a story headlined “Ross Perot and the Call-In Presidency” in the July 13, 1992, issue:

The Perot phenomenon signifies something larger, deeper. It signifies a geologic change in American politics: the growing obsolescence of the great institutions — the political parties, the Establishment media, the Congress — that have traditionally stood between the governors and the governed. The traditional way to achieve and wield power in America is to tame or charm or capture these institutions. Perot’s genius was to realize that for the first time in history, technology makes it possible to bypass them. Win or lose, knowing or not, Perot is the harbinger of a new era of direct democracy…

As for the media, he realized that the proliferation of outlets has created a new game: a way to reach the American people directly, without the mediation of Dan Rather and the New York Times. The Perot campaign owed much of its amazing start to its call-in, soft-news-show launch, which allowed it to get its message out unfiltered. And as for Congress, Perot promises to bypass it and go directly to the American people in the ”electronic town hall” — Nightline with President Perot playing Ted Koppel. It is here, says Perot, that the American people will, in direct communion with the leader, solve those knotty problems that have eluded a clumsy, corrupt Congress.

Krauthammer noted that the Founding Fathers intentionally designed the system of checks and balances and the indirect election of the President through an Electoral College to make sure this kind of “direct democracy” didn’t happen. Parties and Press “evolved as additional filters between the rulers and the ruled,” he wrote. “A century ago you needed party rallies and precinct captains to get the message out. In the age of television and satellites, you don’t.”

Perot figured out he could speak to the party faithful, and everyone, more efficiently. “Why not let one man go on Larry King and send the message out himself, directly?” Krauthammer wrote. “Big Media? The democratization of communications, from CNN to MTV to C-SPAN, means that these dinosaurs can now be bypassed. Congress? A fen of stagnant waters, a den of special interests. To the town hall!”

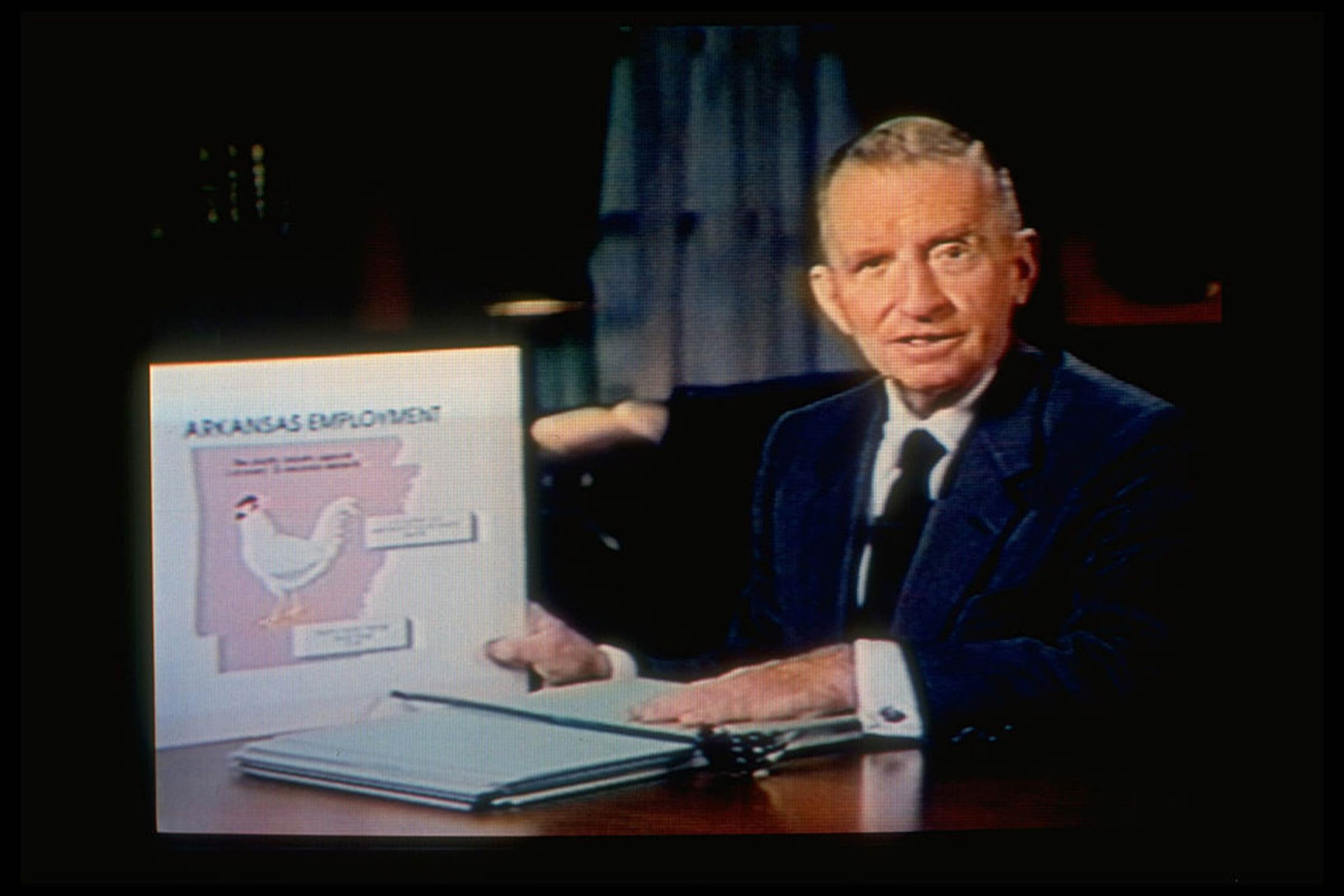

Perot didn’t just go on national TV shows, he created some himself, hokey infomercials on campaign issues that today would be considered viral gold in the YouTube era. More people watched his lecture on the economy that aired in early October 1992 than the baseball play-off game that came on next — “proof that voters will sit still for a straightforward discussion of issues,” TIME noted.

His last program was entitled “Chicken Feathers, Deep Voodoo and the American Dream,” and aired two days before Election Day. Perot argued that most of the jobs that Clinton created while Governor of Arkansas were in the poultry business, warning viewers, “If we decide to take this level of business-creating capability nationwide…we’ll all be plucking chickens for a living.”

TIME critic Richard Zoglin wrote in a Nov. 16, 1992, post-mortem on the Perot campaign that the infomercials’ “crudeness was the source of their appeal” and “an antidote to politics-as-usual slickness.”

In the ’92 election, Perot didn’t carry a single state. In another TIME post-mortem, the magazine pointed out that there’s no substitute for getting out of the TV studios and into the streets, that a better balance between the two has to be struck. But as the largest Democratic presidential field in modern history currently shows, moonshot candidates are seeing an opening to talk about changing the status quo. Many are making the most of new media, this time social media, in addition to the political talk shows and cable news town halls, to get their message across — a form of presidential campaigning that Perot helped popularize.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com