Exactly a year after the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo began, health officials underscored that a coordinated, consistent global response is necessary to keep the public-health emergency of international concern under control.

“I never thought that, after one year, we’d be talking about the same outbreak,” United Nations Ebola Emergency Response Coordinator David Gressly said at a press conference Thursday. “It will be a long fight. It will be hard fight. We need vigilance. It will take discipline.”

The outbreak, which has infected around 2,600 people and killed almost 1,700 since it began a year ago, was declared an international emergency after the World Health Organization (WHO) on July 14 confirmed a case of Ebola in the DRC city of Goma, a transit hub near the Rwandan border that has about 2 million residents. On Wednesday, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced that another case had been confirmed in Goma—and while the two diagnoses do not seem to be related, the news has raised fears of continuing spread in the populous city. In June, two people, including a 5-year-old boy, also died from the Ebola virus in neighboring Uganda.

Gressly also said Thursday that the Rwandan border with the DRC remains open, despite earlier reports to the contrary. He emphasized that the WHO, upon declaring the outbreak an international public-health emergency after three times declining to so, directed countries not to restrict travel or trade with the DRC. Doing so, the WHO’s Margaret Harris said, just “sends an epidemic underground.”

Instead, Gressly said ending the outbreak will depend on consistent funding from the international community and coordinated efforts to fill in geographic gaps in Ebola response, so the disease cannot spread further. It is also crucial to stop interruptions in care due to attacks on and mistrust of health care workers, he said.

Dr. Henry Walke, incident manager for the CDC’s 2018 CDC Ebola response, told reporters on Thursday that the CDC is still committed to fighting the outbreak one year later. Walke said that the rate of new infections does not appear to be slowing down, and that the CDC is planning to double the number of experts it has deployed in the country from 15 to 30.

Walke said that the efforts to combat the outbreak have been hampered by the unstable security situation in the area of the outbreak and the mistrust of public healthcare in the affected communities.

“If the security situation improves, we would rapidly increase our staffing,” Walke said.

The DRC has been at war since 1994, involving complex conflicts internally between rebel groups and externally against neighboring countries. Much of the conflict is concentrated in the eastern part of the DRC, where both militia and official security have been accused of mass violence, leading to a culture of mistrust of officials and outsiders.

More than an estimated 5.4 million civilians have died in the conflicts. Many aid workers on the ground treating Ebola patients have become the target of attacks, forcing several aid centers to close. Misinformation spread by some politicians have also created an air of mistrust in foreign workers and rumors that Ebola doesn’t actually exist. All of these factors have prevented an end to the outbreak.

“It’s not biology, it has nothing to do whatsoever with biology,” says Laurie Garrett, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and expert on infectious diseases. “This is a 100% military/political set of obstacles… the issue is that the people trying to stop the epidemic are being shot at.”

When did this Ebola outbreak start?

On August 1, 2018, the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale confirmed four cases of the Ebola virus in the DRC. It is unclear what started the outbreak in August, according to Garrett, but organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO) immediately declared an outbreak. Further investigations found a concentration of Ebola cases in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces in eastern DRC, bordering Uganda.

By September 5, 2018, there were 89 confirmed deaths, and by the end of the year 357 people had died.

Containment since then has proven difficult, and an average of 13 new cases are still reported daily, according to a Thursday statement from the Red Cross.

Why has it been so difficult to contain?

No other country in the world has more experience with Ebola than the DRC, Garrett says, and the country has been successful at ending many past epidemics, even ending an outbreak as recent as July 2018. But eastern DRC presents a different set of challenges, where a lot of the country’s conflict and violence is concentrated. “This is the most difficult environment in which an Ebola response has ever been attempted,” Gressly said Thursday.

An estimated 4.5 million people are currently displaced in the DRC, according to the International Rescue Committee. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) estimates the number of people displaced in 2017 alone was 4.9 million. More than 20,400 peace keepers have also been deployed to the country. CFR estimates the country’s death toll due to war has surpassed 5.4 million, where kidnapping, sexual violence and robbery are common.

“It’s not clear that ramping up the response would make a difference in the context of a war zone,” Garrett, a former senior fellow on global health at CFR, says. She says she believes the epidemic has the potential to turn into an endemic.

To add to the difficulty, some politicians in the DRC have spread rumors that Ebola doesn’t exist, or that it was brought to the DRC by foreigners. A 2018 study found that 25.5% of North Kivu residents didn’t believe Ebola was real.

“Pouring more people in there, especially white-skinned people, Asian people, non-Africans, pouring them in there only can draw more of the conspiracy theories,” Garrett says. “And they can become more targets for the thugs and the armed bands and military groups.”

Yet others, like Nicole Fassina, an Ebola operations coordinator with the International Federation of the Red Cross, remain optimistic.

One way the Red Cross has responded to the spread of false information is by regularly going door-to-door in various communities to collect information on what rumors people are hearing. They counter those rumors in public statements.

“This is a really important part because it allows us to adapt our approach based on what we’re hearing,” Fassina says. “It’s a community-led approach that will end this outbreak.”

A spokesperson for WHO echoed that sentiment.

“We have the people, the tools, the knowledge, and the determination to end this outbreak but what we need is the sustained political commitment of all parties, so we can safely access and work with communities to beat the virus & end the suffering & loss of life,” WHO said in a statement to TIME. “Working closely with communities is the only way we can end the outbreak.”

After a string of fires at aid centers and shootings at aid workers in February 2019, Doctor’s Without Borders was forced to leave the DRC. At least two aid workers were killed and one was kidnapped, according to the U.N. In an earlier incident, 15 U.N. peacekeepers were killed, and 53 others were injured in North Kivu. Attacks have continued at various other centers, causing those who are sick to fear getting help.

“This is unprecedented,” Garrett says.

How many people have died?

In total, there have been 1,696 confirmed deaths associated with the DRC outbreak. A DRC woman and her 5-year-old grandchild died of Ebola after crossing the border into Uganda. As of mid-June the Uganda Ministry of Health had confirmed a third case.

There’s a 67% fatality rate for those who have contracted the virus in the DRC. The highest fatality rates have been in North Kivu, where more than 1,500 people have died.

Fassina returned home to Nairobi, Kenya after spending four weeks in North Kivu. She described the situation on the ground as disheartening. It is still possible for the virus to be contracted after the infected person has died, making mourners especially susceptible to the disease. The Red Cross has implemented a Safe and Dignified Burial system, working with local community members to handle bodies in a way that is culturally respectful.

“If someone is taking away your loved one without being able to say goodbye in a manner that allows you some level of peace of the situation, that can be really difficult,” Fassina said. “We have to make sure that even though this is a medical outbreak, there’s still a very personal element that can’t be forgotten.”

What has the response been?

Prior to the WHO’s declaration of an international public-health emergency, the international response to the outbreak had been minimal, according to Garrett. The WHO’s declaration, however, was meant to intensify and streamline the global response to the outbreak.

The U.S. State Department issued a do not travel warning to North Kivu, Ituri and several other eastern DRC provinces.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control announced in June that it would be activating an Emergency Operations Center in Eastern DRC. Since June 11, 187 CDC staff had completed 278 deployments to the DRC, according to a June statement by the CDC.

“Through CDC’s command center we are consolidating our public health expertise and logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort to bring this complex epidemic to an end,” CDC Director Robert R. Redfield said in a statement.

Part of Fassina’s work includes building a rapport and relationship between affected communities and Red Cross aid workers to ensure cultural traditions are respected.

The Red Cross has had a presence in the DRC for nearly 100 years. Other organizations on the ground are WHO, the International Rescue Committee, Human Rights Watch, Africa CDC, various U.N. agencies, and dozens of NGOs and faith-based aid organizations.

“It’s only by being a part of these communities that we can listen to them properly and know how to respond when an outbreak comes up,” Fassina tells TIME.

The World Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility has sent more than $20 million to support a six-month response plan to the outbreak.

How does the 2019 Ebola outbreak compare to the 2014 outbreak?

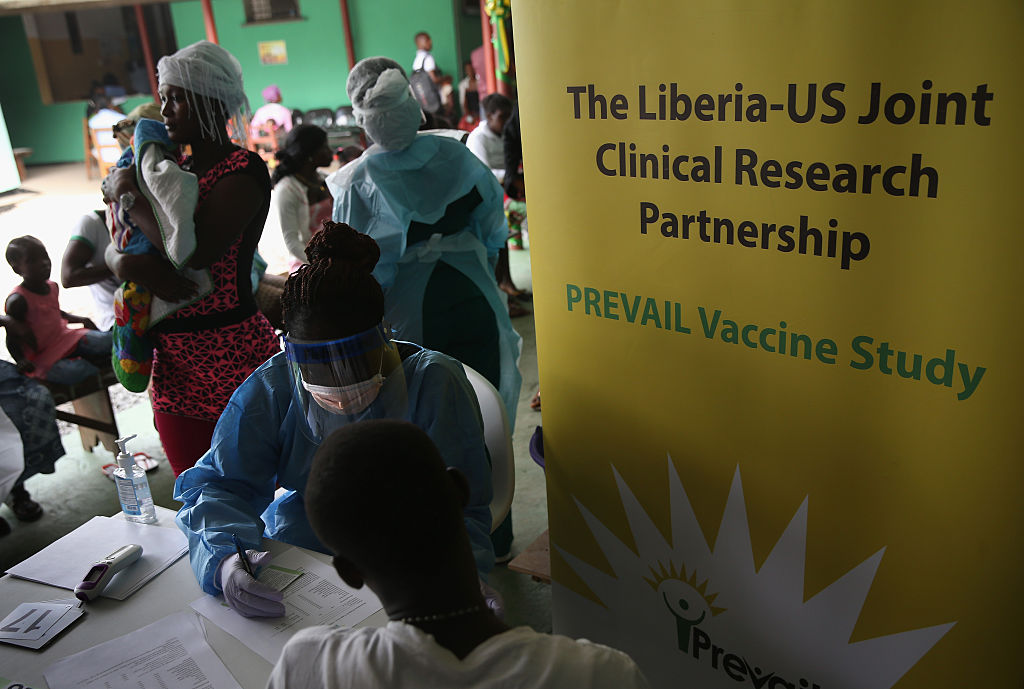

The global response to the 2014 epidemic in western Africa was also slow at first. In March 2014, WHO declared an outbreak after 49 confirmed cases in Guinea, several months after the first case was detected in December 2013. By July 2014, the virus had spread to Sierra Leon and Liberia. In August, after the virus spread to Nigeria, WHO declared an international emergency, 932 deaths later.

The U.S. CDC activated its response centers in west Africa in July 2014 and trained 24,655 healthcare workers. The U.S. Department of Justice also deployed military to west Africa in April 2014. Later in the year, one person in the U.S. was confirmed to have died of Ebola.

The 2014 outbreak is still the worst Ebola epidemic in history. A total of 11,325 died, and there were 28,652 total cases.

What public health considerations should people take?

The WHO emphasized that countries should not restrict travel to or trade with the DRC, and that screening is not required outside the immediate region. Within the region, however, officials have urged more precautions. The Uganda Minister of Health, Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng, called on Ugandans to avoid touching each other, not even handshakes, until the outbreak has been resolved.

WHO has been distributing best practices for those in proximity to the disease, which include minimizing contact with others, and how to properly hydrate a person who is sick. WHO also encourages those who have survived Ebola to play a role in spreading accurate information on the ground, and recommends vaccinations for those on the ground in crisis areas.

The disease spreads through contact with bodily fluids and contact with infected animals and aid workers are highly susceptible to catching the virus.

“I really commend the frontline workers who risk their lives every day to respond,” Fassina says. “The approach and the way forward is clear, and we are prepared for this. But we really need to make sure that we are adapting and listening to those communities and having a community-led response.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com and Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com