The Goddess of Democracy smiled on China for exactly five days. The papier-mâché likeness of the Statue of Liberty appeared in Tiananmen Square as protests convulsed Beijing and other cities seeking to unshackle the world’s most populous country from endemic corruption.

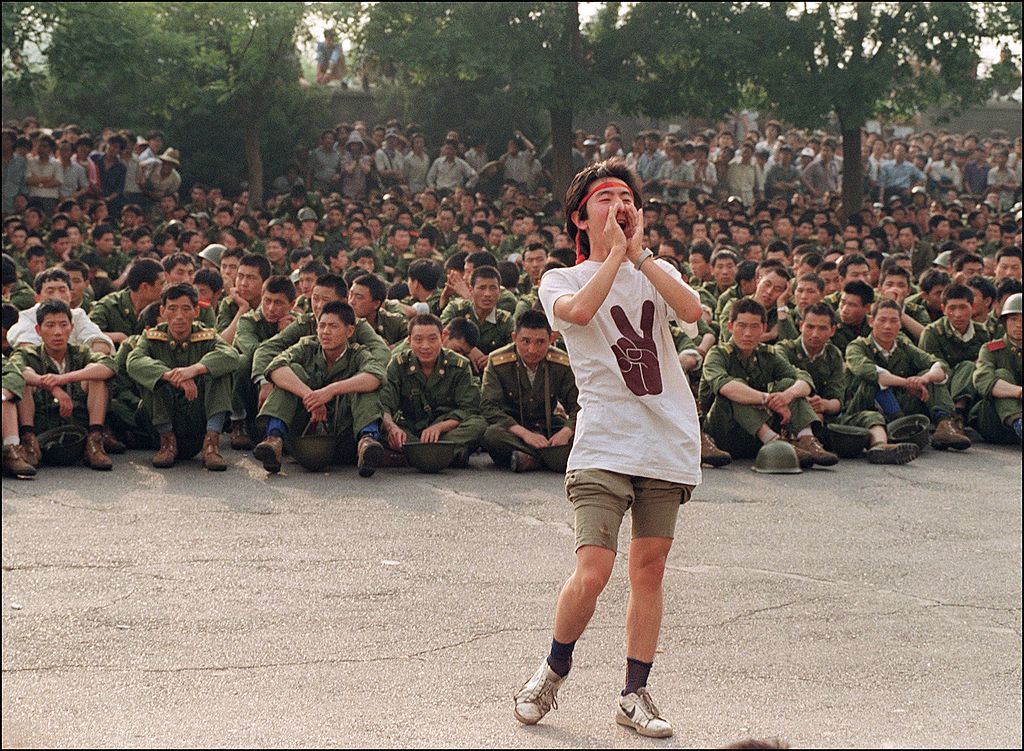

Their calls for political reform were answered in the early hours of June 4, 1989, with a bloody military crackdown that crushed the movement and toppled its symbols. The massacre at Tiananmen killed hundreds, possibly thousands, of the students and laborers who joined massive gatherings lasting more than a month. The movement, favoring democracy and reformist policies that caused rifts within the Chinese Communist Party, or CCP, had spread to hundreds of cities before the government resolved to disperse it with brute force. Military tanks rolled into Beijing, where soldiers opened fire with assault rifles on the unarmed demonstrators who tried to stop their advance.

And yet in the West, a certainty remained that China would eventually resurrect the dream of democracy that was deferred that night. Thirty years later, many are still waiting for the Middle Kingdom to liberalize, though the CCP’s grip on power has arguably never been tighter. To survive the upheaval, its leadership rewrote their social contract; the post-Maoist effort of “reform and opening up,” whereby China established its own brand of market-economy socialism, was ultimately accelerated but at the expense of political freedoms. By some measures the trade-off was tremendously successful. At the time of the Tiananmen rallies, China’s GDP per capita compared unfavorably to Gambia’s; by 2030, if not before, many indicators predict China’s economy will eclipse the U.S.

“The Chinese government used economic benefits to persuade people they can live a good life under the CCP’s control,” says Joanne Ng, a Guangdong native who was nine years old at the time Tiananmen crackdown and who now lives in Hong Kong. “[While] my classmates enjoy these benefits, the truth is not necessarily so important to them.”

Eventually the West acquiesced to China’s economic momentum on the premise that economic and social liberalization would develop in tandem. In 2000, on the verge of China joining the World Trade Organization, President George W. Bush declared, “Trade freely with China, and time is on our side.”

“Many Western scholars and diplomats predicted that when China… integrated into the global economy it would create a middle class that demanded democracy,” says exiled human rights lawyer and China commentator Teng Biao, a visiting scholar at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute. “But that did not happen.”

China several years ago leapfrogged the “political transition zone,” levels of income that reflect when authoritarian states typically undergo democratic transformation. Transition becomes more likely above $1,000 per capita, and dramatically more likely above $4,000 per capita. In 2018, China hit $9,608, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Biao says the West’s forecast failed to consider that China’s economic metamorphosis was built on the bloody legacy of Tiananmen and relied on the “suppression of political rights and deprivation of human rights.”

Engineering the greatest economic expansion in the world was a matter of self-preservation for the Party, and was never intended to move toward constitutional democracy, he says.

“[The Tiananmen massacre] changed China and to a certain extent the world as it is linked with the ‘China miracle,’” says Biao.

“There is a lesson the world could learn here,” he adds, “engagement as a policy is not wrong, but engagement… that obscures human rights is morally and politically wrong.”

Read more: Tank Man: TIME’s 100 Most Influential Images

Beyond simply eschewing democracy, Beijing increasingly poses as an authoritarian foil to Western liberalism — acting as a lodestar for developing nations that similarly seek to divorce economic reforms from political concessions. China, President Xi Jinping announced in 2017, presents a “new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.”

For 30 years, the CCP has maintained remarkable stability, escaping some fallout of the global financial crisis and evading the tectonic uprisings that shook many other parts of the world. Should the CCP slip, it warns that chaos would be unleashed on a population comprising nearly one out of every five people on the planet. As one commentator in China’s state-controlled media put it: “As crises and chaos swamp Western liberal democracy,” China “maintains political stability and social harmony.”

As foundational as the crackdown at Tiananmen may have been to the CCP’s current strength, it remains largely invisible to the people. Despite claiming the moral high ground against what it calls a “counter-revolutionary” rebellion, the Party is still sensitive to the fact that its slaughter of students and laborers put a stain on its legitimacy. Beijing has manufactured a cultural amnesia around the June 4th massacre; it’s not taught in schools or mentioned in newspapers, while high-tech censors detect and block any mention of it online. So thoroughly has the memory of June 4th been expunged that the generation born after the incident remains largely unaware of this historic watershed.

“On the surface, Tiananmen seems to be remote and irrelevant to the reality of the rising China, but it remains the most sensitive and taboo subject in China today,” says Rowena He, author of Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China, and member of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J.

Hong Kong is the only place on Chinese soil where the June 4th massacre is openly commemorated. A former British colony, Hong Kong was returned to Chinese sovereignty eight years after the Tiananmen crackdown. Despite initial trepidations, the territory, like the West, had hoped its engagement with mainland China would have a positive, democratizing effect. But instead of introducing freedoms to China, Hong Kong has ended up defending those it already exercised. Its convergence with Beijing has, if anything, illustrated the gravitational force of China’s growing influence.

Remembering Tiananmen in Hong Kong has been viewed as an act of defiance for years, and it has become even more so now that the city’s own democratic future has come under threat. In the run-up to the 30th anniversary, demonstrators marched through the semi-autonomous enclave’s financial district chanting, “justice will prevail” and toting “support freedom” umbrellas. “In China, [people] can’t say anything against the government,” says Au Wai Sze, a nurse in Hong Kong who marched along with her 15-year-old daughter. “So while we in Hong Kong can still speak [out], we must represent the voice of the Chinese people and remind the world of this injustice.”

Read more: ‘The Communists Will Never Allow This.’ Photographer Liu Heung Shing on Documenting Tiananmen

For all its power, China’s government is still deeply paranoid. Today, the regime is “stronger on the surface than at any time since the height of Mao’s power, but also more brittle,” Andrew Nathan, a professor of political science at Columbia University, wrote in Foreign Affairs. The people’s loyalty is predicated on wealth accumulation, which will be difficult to sustain. A sputtering economy, widespread environmental pollution, rampant corruption and soaring inequality have all fed public anxieties about Xi’s ability to continue fulfilling the prosperity-for-loyalty bargain.

“Attitudes are changing,” Nathan tells TIME. “It’s a close race between the human desire for freedom and the state’s capacity for control.” He predicts that the desire for freedom will eventually nudge China toward a more open society, but such a change does not appear imminent because much of the population still lives in fear. “And when it does happen,” he adds, “it might not lead to anything we would recognize as democracy.”

In the meantime, Xi has steered the country in even more illiberal direction. Last year, he changed the constitution to allow himself to rule for life. Faced with trends that could tempt the middle class to seek greater freedoms — more Chinese studying and working abroad, rising private sector employment, proliferation of internet access (albeit heavily censored), and an explosion of religious conversions — Xi has responded by producing the world’s largest surveillance state and amplifying xenophobic nationalism.

“In general, the CCP has taken a diagnostic approach to the problem of staying on top,” says Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a history professor at UC Irvine and co-author of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know. “Beijing has charged scholars and think tanks with studying carefully the various ways that authoritarian systems have democratized, and also how the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia broke apart, and tried to use that information to the CCP’s advantage.”

One of the main lessons, Wasserstrom says, is to “move swiftly and harshly” against any organizations or groups that could provide competing centers of power or escape the party’s control. Beijing spends more on domestic security than on military defense; crackdowns have escalated against religious groups such as Falun Gong and underground “house churches” that emerged in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. Human rights lawyers, Marxist students and feminists have all been targeted by the state as potential threats to its power.

Such is the heft of an economically ascendant China that few world leaders are willing to offer full-throated criticisms, even in the face of Beijing’s most egregious human rights abuses. In the country’s western province of Xinjiang, the world’s largest incarceration of an ethnic minority population continues with little recourse; between one and two million Uighur and other Muslims are currently detained in concentration camps that the state describes as “re-education” centers. When most nations refuse to defy the world’s presumptive superpower, it would be naive to assume that post-Tiananmen, the Chinese populace would inevitably adopt a more critical stance against their own government, when doing so has already cost them so much.

Thirty years after Beijing’s bloody showdown with democracy, freedom seems both more precious and more fragile. No place is this more apparent than in Hong Kong. That this precarious city continues to remember and pay homage to the lives lost on June 4, 1989, shows that what drove protesters to Tiananmen — the struggle for human rights, accountability and a political voice — still exists in China. “Tiananmen may remind of us repression, but it also symbolize[s] the indomitable force of the human spirit,” says He, of the Institute for Advanced Study. “As the desire for freedom and our longing for basic rights is universal, history will witness the Tiananmen spirit, as the power of the powerless, again and again.”

Correction, June 7

The original version of this story misstated Rowena He’s affiliation. He is at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ, which is not part of Princeton University.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Laignee Barron / Hong Kong at Laignee.Barron@time.com