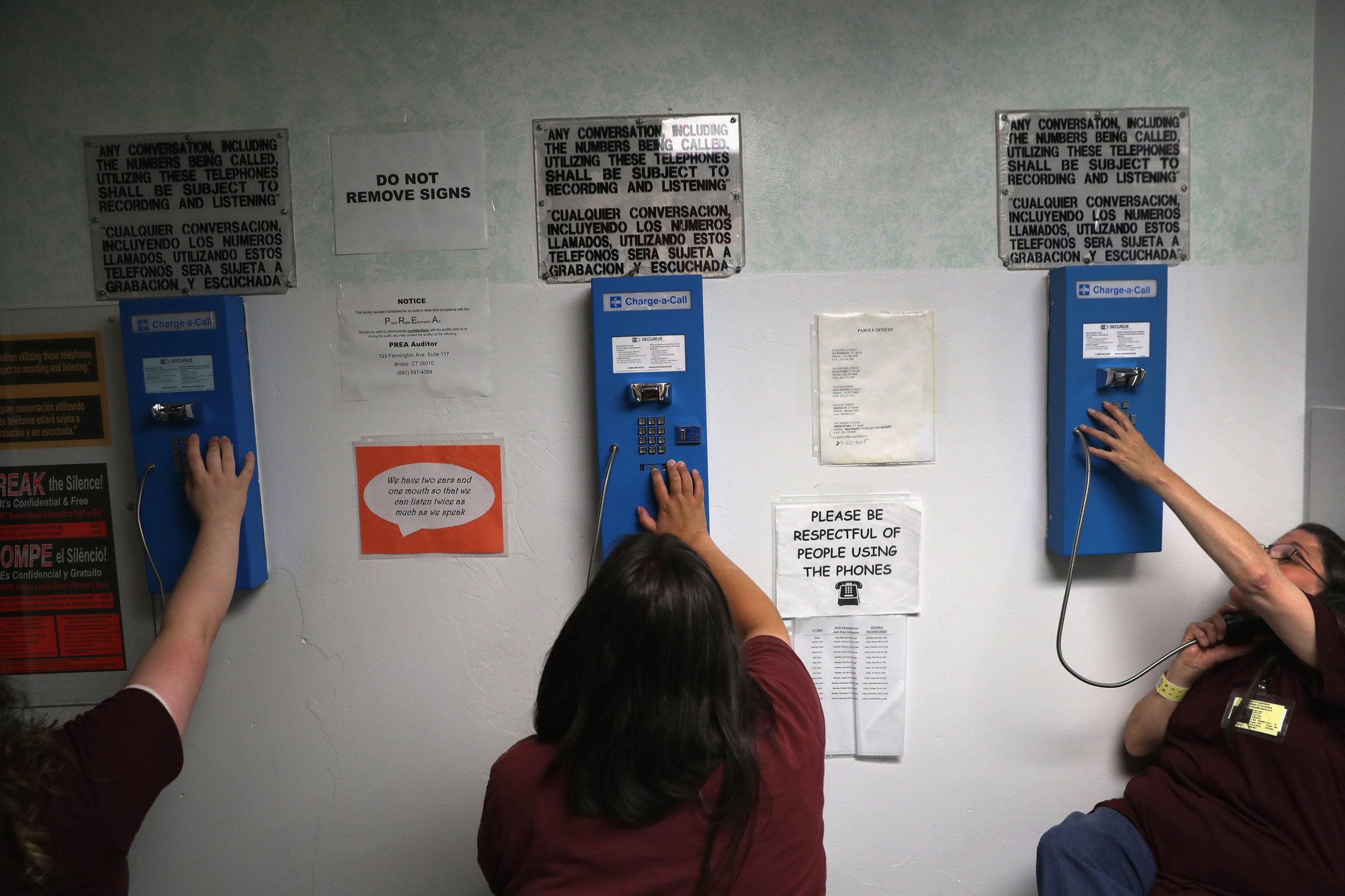

Each time I leave a prison or jail — after a class I’ve taught, an interview I’ve conducted, or a visit with a friend — I walk back to my car and collect my phone from the glove compartment, as I am not allowed to bring it inside. As I sit in the driver’s seat, I check my messages, scan the notifications and return any phone calls that I might have missed. Whether it’s my wife, my parents or my colleagues, I usually don’t think twice about the ease with which I am able to call anyone I want, at any point during the day, for almost any amount of time. But there are days in which I experience a sense of dissonance between this effortlessness and the divergent reality of the incarcerated individuals I have just left. Incarcerated spaces are, by design, replete with insidious and unethical realities, but one of the most infuriating is how much money people in jail and prison are forced to pay if they want to make a phone call to someone on the outside.

This unjust reality, however, could be changing soon for incarcerated people in Connecticut. A new bill making its way through the state’s legislature is seeking to relieve people of having to pay to use the phone while behind bars. Last month, the legislature’s House Judiciary Committee voted to advance H.B. No 6714, a bill that would allow free phone calls for people who are incarcerated. New York City adopted a similar proposal last year, which just recently went into effect. If H.B. No 6714 makes it through the legislature, however, it would make Connecticut the first state in the country to make phone calls free for people in prison. Many advocates feel optimistic about the legislation passing, though there are now reports the governor is stonewalling. The bill’s supporters in the state House of Representatives fear that if they don’t act immediately, the Senate will not have time to pass it by the summer recess.

But Connecticut should pass this bill. Every other state in the country should pass bills just like it. And so should the federal government.

Connecticut, with the exception of Arkansas, charges more for a phone call in prison than any state in the country. Connecticut charges $4.87 for a 15-minute collect call, which is 32 times more than the state with the lowest phone rate, Illinois, which charges 14 cents for 15 minutes. (That figure does not include jails in Illinois run by counties rather than the state; according to the Prison Policy Initiative, they charge $7 for a 15-minute call.)

The Connecticut bill, as it is currently written, would also ensure that if the state were to implement video conferencing, which a growing number of states have begun to do, that such communication would remain free as well—an important provision, given the rising cost of video-conferencing in other states.

Over the past few decades, the prison phone business has grown into a financial behemoth, an estimated $1.2 billion industry largely dominated by two companies, Global Tel Link and Securus Technologies, which pay both the state and municipalities for doing business. In 2018, for instance, Connecticut state prison residents paid $13.2 million for phone calls, nearly 60% of which Securus then paid back to the state. This disincentivizes states from bringing lower phone rates to prisons because they share in the revenue generated from these calls and often rely on this revenue to operate. In Connecticut, Republican representative Craig Fishbein, who opposes the bill, expressed sentiments that reveal the tension between the existence of such financial incentives and justice for the families impacted by its design. “Somebody has to pay for this service to be rendered,” Fishbein said. “On the other hand, if people only knew that the state of Connecticut is profiting from communications between family members and those that are incarcerated — I think that is absolutely horrible.”

These perverse economic incentives have long undermined the decades of research demonstrating how maintaining close family ties can help lower recidivism rates and increase the likelihood of an inmate’s successful reentry into society. For example, a 1972 study, “Explorations in Inmate-Family Relationships,” stated that “the central finding of this research is the strong and consistent positive relationship that exists between parole success and maintaining strong family ties while in prison.”

A 2012 report from the Vera Institute of Justice reaffirmed this sentiment, asserting that maintaining contact with family members during one’s period of incarceration makes a person more likely to be successful in reintegrating. It concludes, “Research on people returning from prison shows that family members can be valuable sources of support during incarceration and after release. For example, prison inmates who had more contact with their families and who reported positive relationships overall are less likely to be re-incarcerated.”

This pain is not only felt in state penitentiaries. For those in federal prison, the cost of prison phone calls has been in a flux. In 2013 the FCC, which then had a Democratic majority, put a cap of 21 cents a minute on interstate calls. In 2015, they extended the caps to apply to in-state calls, which are about 92% of all calls made, and made them as low as 11 cents per minute. Afterward, however, the FCC was immediately sued by the major prison phone companies, and in 2017 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit struck down the 2015 caps, saying the FCC had exceeded its authority. Since that ruling and the transition of the FCC to being a majority-Republican entity led by Ajit Pai, a Republican, there has been little movement on the issue. And although last year, Senator Tammy Duckworth introduced a bipartisan bill, the Inmate Calling Technical Corrections Act, to lower the costs of prison phone calls and to ensure that phone companies are not able to economically exploit incarcerated people and their families, but it was referred to committee. (It has not since been reintroduced.)

To be sure, being able to make phone calls from prison or jail is no substitute for having visitors. Nothing can replace a hug from one’s child, nothing that can replicate the embrace of a parent or partner. As the incarcerated poet Timothy TB wrote in “A Poem From a Father to His Youngest Son,” even video calls fall short of creating the tactile connection that is so important for those who are incarcerated.

The worst pain I’ve ever felt

was looking at you, reach for me

through a video screen and I couldn’t

touch you; right then, I knew

what it felt like to die, a living

death—

Connecticut’s proposed bill recognizes the difference, and is written to ensure that eliminating the cost of prison phone calls or video conferences won’t be used as justification for reducing personal visit time, as some places have done.

In addition to limiting a person’s ability to stay in contact with their loved ones, the price of phone calls can make it difficult for people to communicate with their attorneys. The Missouri State Public Defender System told the FCC in a 2013 letter that the costs on phone calls for people in jail “reduces our ability to communicate with our clients about their cases, diminishes the quality of representation we are able to provide, and thus risks denying clients their Sixth Amendment right to effective counsel.” This is especially important for people in jail, where the majority of people have not been convicted of any crime. Phone calls are often the only way they are able to mount a meaningful legal defense.

For decades, millions of people have been systematically denied access to one of the tools that research has demonstrated time and time again is most effective in improving an incarcerated person’s morale, helping them maintain relationships with their loved ones and their support system and enhancing their ability to more smoothly transition back into society. If Connecticut passes this bill, it will be a model that the rest of the nation can follow.

Prisons have long been predicated on social isolation, even as such isolation has long been proven to reduce one’s ability to successfully reintegrate into the world upon release and have a future detrimental impact on public safety. Ensuring that people are not prevented from staying in contact with their loved ones or their attorney — that a child growing up with an incarcerated parent feels just a little less distant — is a small step in chipping away at the system of mass incarceration that has swollen over the past half-century. For some a phone call is simply a phone call, but for others it is one of the only ways to stay connected to a world you’re scared will forget you.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com