As Democratic presidential hopefuls unroll their platforms for the 2020 presidential election, some of the hot-button issues they’re discussing, such as immigration and healthcare, will sound familiar from past presidential races.

But one idea that has popped up in the campaigns of Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Beto O’Rourke and others may be unexpected: changing or abolishing the Electoral College.

In some ways, it’s not actually surprising that more attention is being paid to the Electoral College. Two of the last three U.S. Presidents — Donald Trump and George W. Bush — were elected to their position without winning the popular vote. That’s possible because when Americans cast their ballots in a presidential election every four years, they’re not voting directly for President but rather for “electors” who promise to vote for a particular candidate. The electors from all the states come together to form the Electoral College and select the President. Because of the way the number of electors per state is determined, an individual vote from a sparsely populated state is worth more in the final count than a vote from a densely populated state, so it’s possible to win the Electoral College vote while losing the popular vote.

Some 2020 candidates argue that abolishing the Electoral College would bring the country closer to the ideal of “one person, one vote.” Proponents also argue that the process would increase voter participation, especially in states that are deeply red or blue, whereas some voters today are left feeling that their vote cannot affect the result.

“Every vote matters, and the way we can make that happen is that we can have national voting, and that means get rid of the Electoral College,” Warren said during a CNN Town Hall.

A slight majority of Americans agree. About 53% of American are in favor of a constitutional amendment to require a popular vote, compared to 43% who agree with maintaining the Electoral College, according to a survey by NBC News and the Wall Street Journal.

However, abolishing the electoral college has become more of a partisan issue since the 2016 election. According to Gallup, in 2012 54% of Republicans and 69% of Democrats were in favor of amending the constitution. By late November 2016, 19% of Republicans and 81% of Democrats were in favor of such a constitutional change.

Reasons for supporting the electoral college have shifted over time.

Some today argue that the electoral college encourages candidates to campaign across more diverse geographical areas and helps by breaking down the complex process of voting into more manageable areas. Back when the Constitution was being written, however, the process was a compromise between those who believed the President should be elected by Congress and those who thought the chief executive should be elected by a majority of the people. The framers were also concerned that it might be difficult for voters to learn enough about presidential candidates. The system also gave greater power to more sparsely populated states, and to states with many slaves. States were able to count enslaved persons toward their populations without giving them the right to vote (or even counting them as full people) and, as constitutional scholar Akhil Reed Amar has argued on TIME.com, the process gave the country a “pro-slavery tilt”; for 32 of the county’s 36 first years, a white slaveholder from Virginia was President.

Defenders of the Electoral College also have a major advantage. The process is enshrined in the Constitution, which means that a Constitutional amendment would be necessary to change it. There is a precedent for changing the system — the 12th Amendment clarified the distinction between the electors’ votes for President and Vice President, and the 23rd Amendment gave Washington, D.C. the right to electoral votes — but that doesn’t make it easy.

No matter whether the Electoral College changes or stays in place, however, the Electoral College has already left an indelible mark on some of the most consequential moments in American history, determining who was in power during the Sept. 11 attacks and the Reconstruction period after the Civil War.

Here’s a full list of Presidents elected by the Electoral College without winning the popular vote.

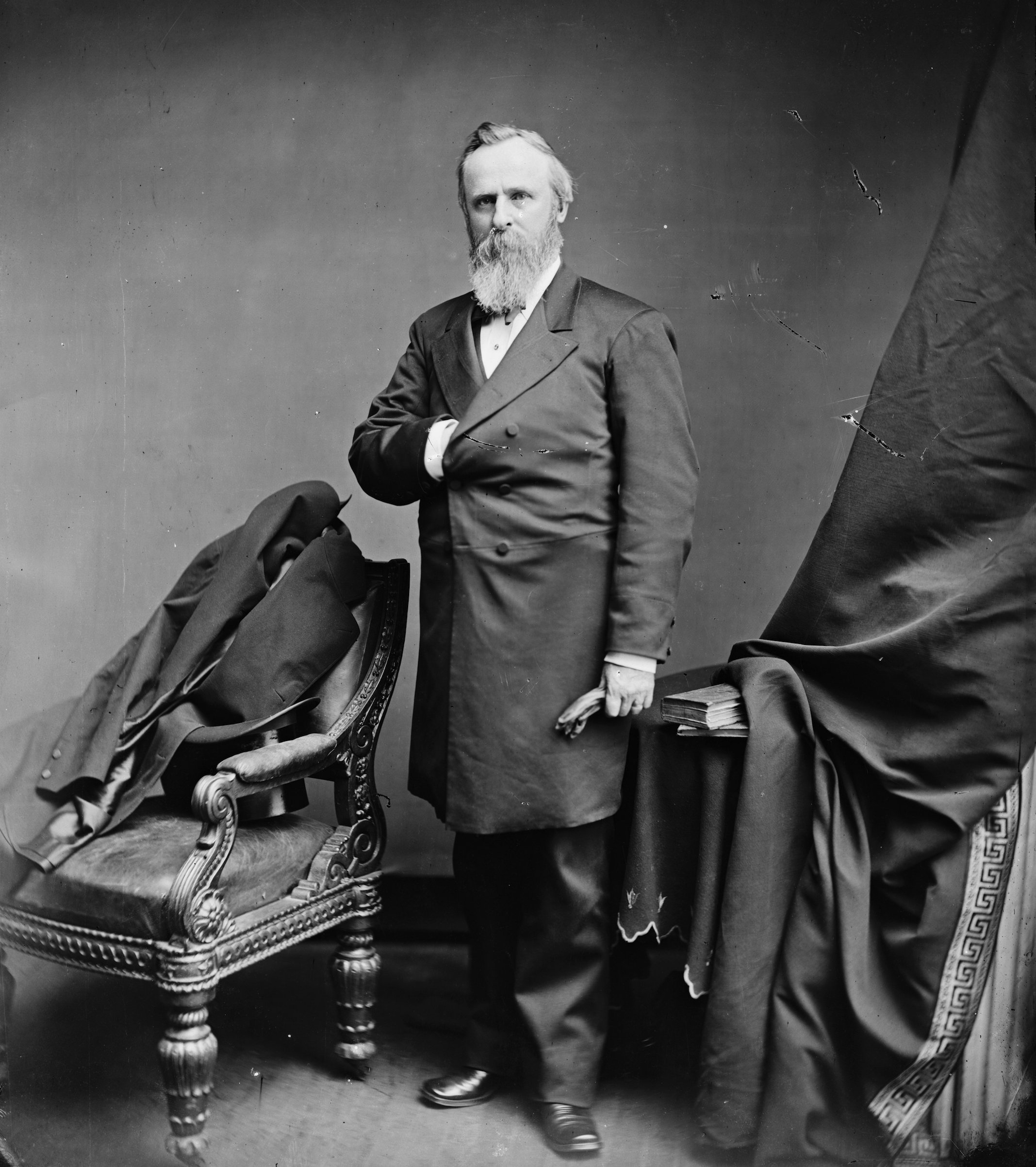

Rutherford B. Hayes (1876)

Modern elections have been known to get ugly, but the election of 1876 may be the most contentious race ever. When Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican governor of Ohio, took on New York Democrat Samuel Tilden, the claws came out; for example, rumors circulated that Tilden was single because he had syphilis. The election is also the only race in American history which the victor initially won both fewer electoral votes and fewer popular votes than his opponent.

Tilden won 184 electoral votes — one shy of the number needed to win — to Hayes’ 165 votes. However, the election was riddled with voter fraud and suppression in the post-Civil War south. After the election, the validity of the votes in Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina and Oregon was challenged.

Congress ultimately came up with a special commission composed of 15 congressmen and Supreme Court Justices, who were tasked with devising a solution. The commission’s decision became known as the Compromise of 1877, which effectively put an end to the Reconstruction era in the south. In exchange for Democrats allowing Hayes the White House victory, Republicans agreed to remove all federal troops from the south, leaving Democrats free to reclaim control of the region and local governments to subjugate African Americans who had so recently been freed from slavery.

Ultimately, the electoral college vote was decided to be 185 to 184 in Hayes’ favor, with Tilden winning 254,000 more popular votes.

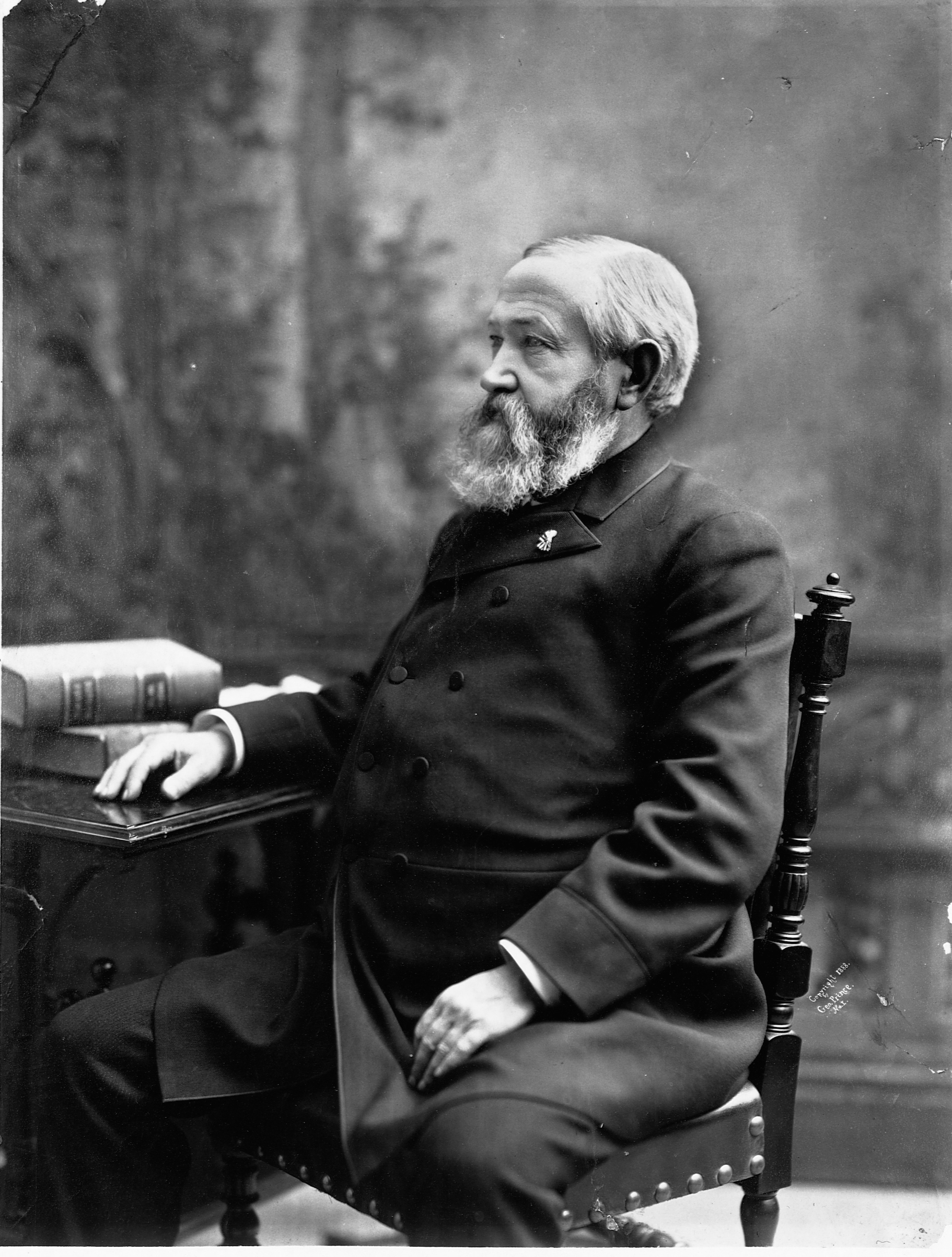

Benjamin Harrison (1888)

The election of Benjamin Harrison, an Indiana Senator and Republican, over Democratic President Grover Cleveland was also riddled by corruption. Both parties were accused of using “floaters” — citizens who were willing to sell their votes — to sway the election. Public attention was drawn to the practice after an Indiana newspaper published a letter, apparently written by a Republican National Committee official, which instructed party workers on how to handle floaters.

Harrison, whose campaign was better organized, was able to capture Indiana, his home state, even though it had gone to Cleveland in the previous election. Cleveland captured nearly 91,000 more popular votes, but lost the electoral college to Harrison with a vote of 168 to 233.

Cleveland got his revenge four years later, however, when he defeated Harrison with an electoral vote of 277 to 145. He became the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms.

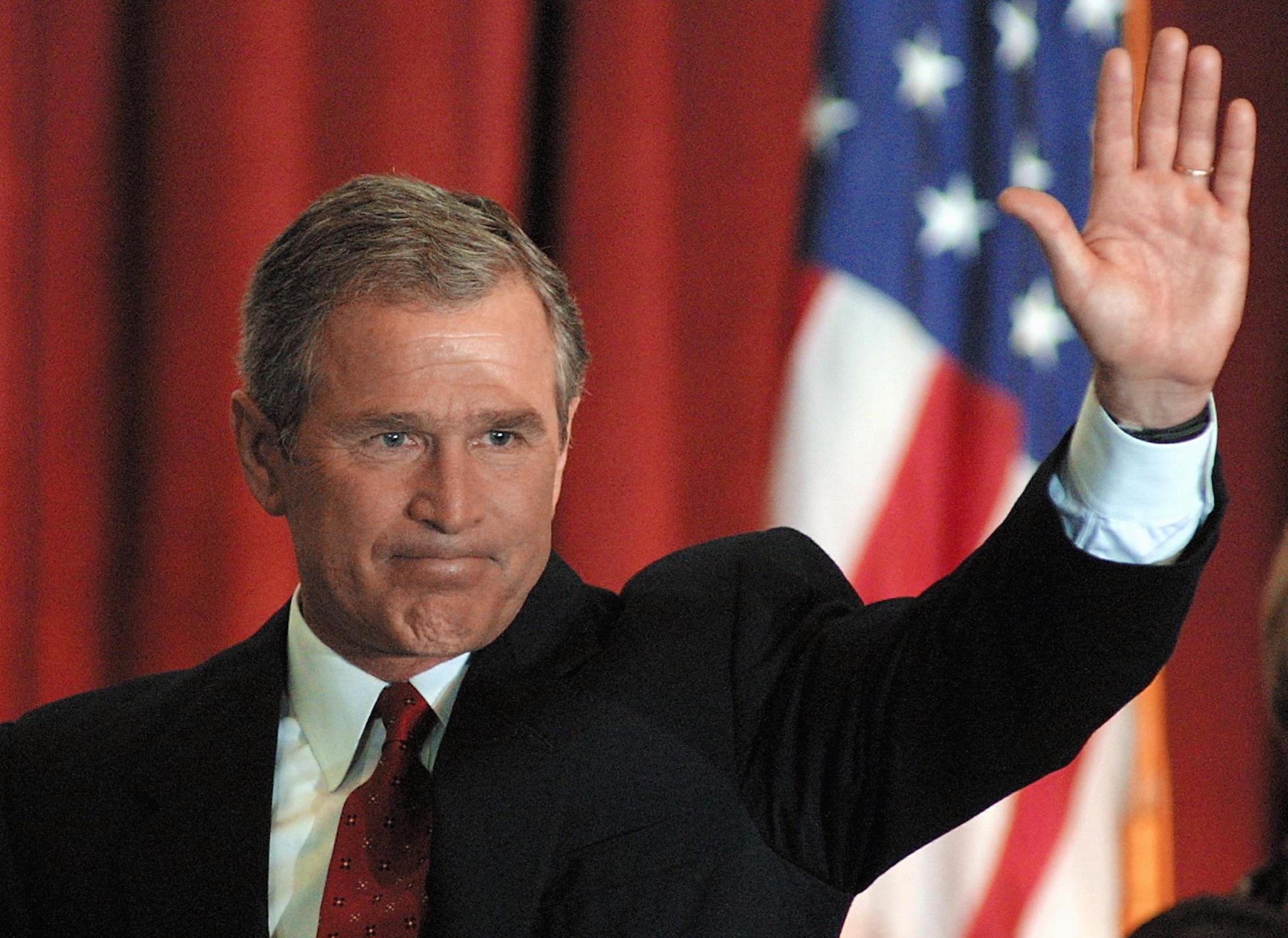

George W. Bush (2000)

It took 112 years for there to be another election where the victor won fewer popular votes. In 2000, Vice President Al Gore took on George W. Bush, the governor of Texas and the son of the 41st President. Bush won 271 electoral votes to Gore’s 266 votes, but Gore won 500,000 more popular votes.

The election was so close in Oregon and New Mexico that the victor wasn’t called for a few days, but the real test came in Florida. The race was so close that Florida law required the votes to be recounted, and then the Florida Supreme Court further ordered that ballots in four counties needed to be counted again. However, on Dec. 12, 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5 to 4 that the Florida Supreme Court’s ruling was unconstitutional because not counting ballots by uniform methods violates the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the election, ultimately most Americans did not feel that the events had undermined their sense of the legitimacy of either the Supreme Court or Bush, according to polling by Gallup. About 66% of Americans told pollers that the election did not undermine their respect for the Court, and 83% said they’d accept Bush as the legitimate President.

However, another institution did take a hit to its reputation: the Electoral College. On Dec. 15 and Dec. 17, 2000, 59% of Americans said that the Constitution should be amended so that the candidate who wins the most votes nationwide wins the presidency.

In later years, Gore joined that majority. In 2016, he told NBC News that he believes that the Electoral College should be eliminated to encourage voter participation.

“We’ve got to get back to harvesting the wisdom of crowds in the United States. We’ve got to get back to the kind of conversation of democracy that allows good ideas to rise to the surface,” he said. “Our democracy has been hacked now. It’s pathetic how our system is not working today.”

Donald Trump (2016)

In an election that surprised many political experts and pollsters, real estate mogul Donald Trump defeated former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, taking in 304 electoral votes to Clinton’s 227 votes. However, Clinton took in 2.8 million more popular votes.

While the full impact of the election remains to be seen, it quickly generated conversation — especially among Democrats — about changing the Electoral College. Clinton had called for the abolition of the electoral college after Gore’s 2000 loss. She reiterated this position after her own defeat.

“We’ve moved toward one-person, one-vote, that’s how we select winners,” Clinton said in September of 2017.

Although Trump had previously criticized the Electoral College process, he seemed to change his mind after his victory.

“The Electoral College is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play. Campaigning is much different!” Trump tweeted on Nov. 15, 2016. But, he said, he thought he could have campaigned just as well in a popular-vote system — so he didn’t believe that the Electoral College affected the outcome much at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com