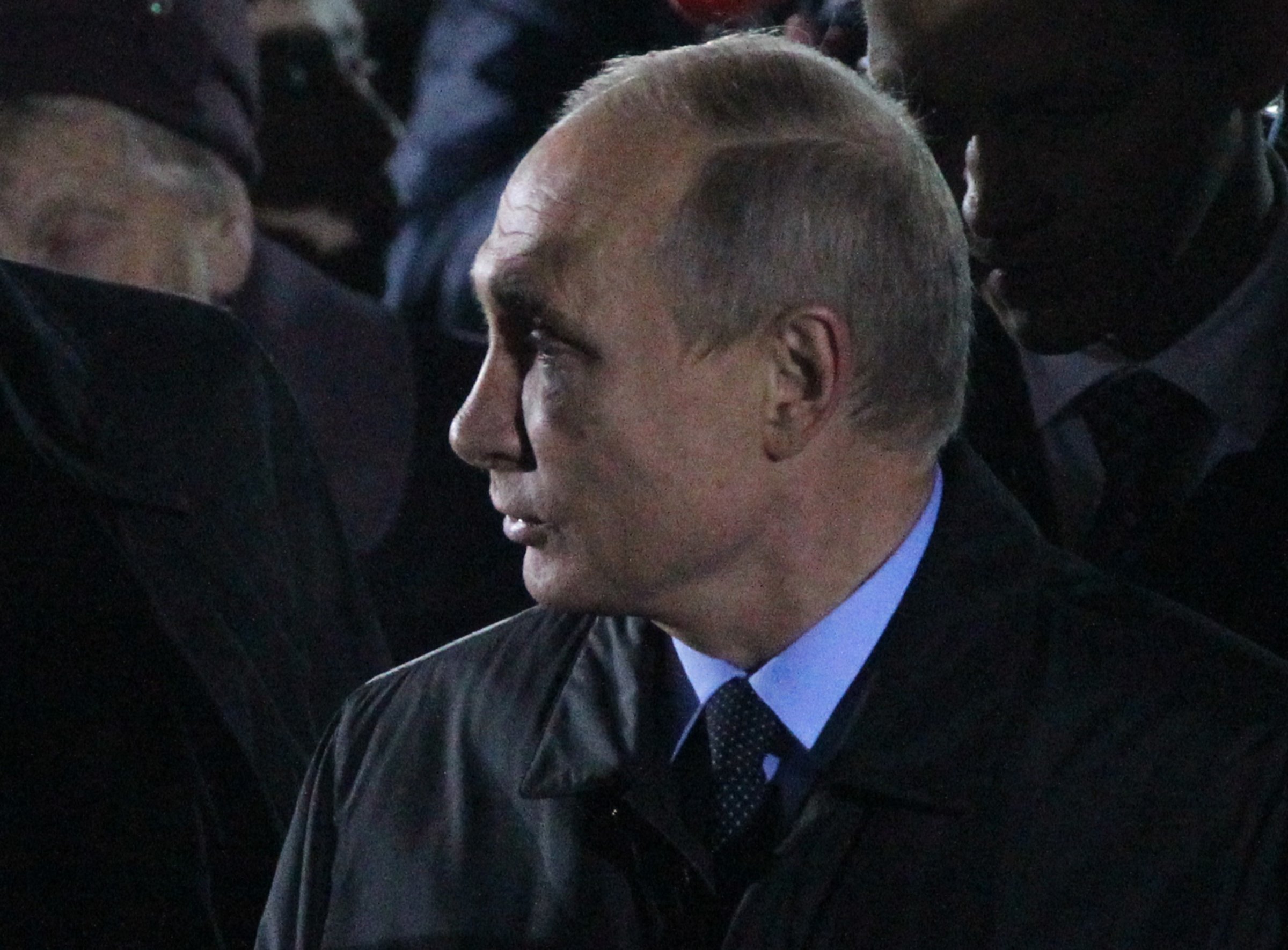

Vladimir Putin appears to stride the globe like a political goliath, a mix of Peter the Great and Joseph Stalin. Whether in Syria or Ukraine, the Russian President flexes his muscles and the world seems to quake with anxiety. There is now little doubt that Putin has skillfully maneuvered Russia back into a position of global prominence following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, which he has called the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” He poured billions of dollars into modernizing his military machine and plunged into the exciting but murky world of new media technology, transforming it into a formidable weapon of political warfare.

At home he has reached deep into Russian history, religion and mythology to strengthen his image and grip on power, associating himself with successful czars such as Peter and Catherine in the 18th century; with the Orthodox Church, which stresses “traditional values” of faith and patriotism; with conservative philosophers like Sergei Uvarov, whose writings in the mid-19th century stressed “orthodoxy, autocracy and nationality”; and even with Stalin’s discredited dictatorship.

In projecting an image of expansive personal power and influence, Putin leaves little to chance. He wears a large cross, given to him by his mother, that he swears was blessed in the Holy Land. He speaks with reverence of the year (988) when Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus led the Christianization of the Russian people. On special occasions, he rides horses bare-chested across the Russian tundra. He knows in his gut the Russian people admire such a strong vozhd, and he is determined to be their hero.

But is he? While Putin’s successes have been made obvious, his failures have been placed on the back burner, where they simmer in anger and disappointment.

Start with the economy. It has been stagnating from slipping oil prices and the Western sanctions imposed in 2014, after Russia seized Crimea and instigated a revolt in southeastern Ukraine. Across the country, strikes (which are increasingly illegal) have sprung up—short, spontaneous and a sign of deepening labor unrest. Meanwhile, salaries have been withheld, sometimes for months. Families have been denied financial compensation for children who die on duty; this was once a given.

By now the revolt in Ukraine has stale-mated, with the conflict a costly continuing endeavor. The Russian intrusion into the Syrian civil war did embarrass the U.S.—and save Bashar Assad’s regime—but it also carries the danger of wider conflict, possibly involving the U.S. Russians have begun to ask, Is it worth it?

Still, if pollsters say Putin’s approval ratings are in the 80s, the question is: Why worry? But Putin does worry, and deeply. The evidence lay in the creation, on April 5, 2016, of the Russian National Guard, a domestic force numbering an estimated 350,000 troops that is loyal only to Putin. The general in charge of the guard is Viktor Zolotov, who for many years was Putin’s personal bodyguard. When he decides to employ his troops, he is not obliged to receive approval from anyone other than Putin—not parliament, not the established military, no one. He and his troops operate as an independent force.

Why would Putin need a powerful praetorian guard? He already has a sophisticated, re-equipped military force. A study of the man strongly suggests that, whatever polls may say, Putin nurses a deep fear of his own people. He is afraid that one day they will rise up against him, as they did against the government 100 years ago on Nov. 7, 1917. One similar uprising looms large in his own biography. Putin was a KGB officer in Dresden in the late 1980s when a mob of angry Germans stormed his headquarters after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As he tried desperately to burn official papers, he telephoned Moscow for instructions. No one answered his call. Stunned, he vowed, never again.

In power, Putin has seen other popular uprisings. A “color” revolution in Ukraine in 2004 frightened him, and he was at the time unable to suppress it. In ’08, Georgia exploded; this time Putin used military force to crush it. Ukraine surged again in ’14, so Putin—concerned that the Ukrainians’ embrace of freedom and independence might spread to the Russian people—took military action. He occupied Crimea, and soon thereafter moved into southeast Ukraine, which still smolders.

Putin may strut on the global stage, but the creation of his guard betrays consuming doubts about his political longevity. Czar Nicholas II had such a guard too, called the okhrana. It protected that ruler up until 1917, when the Russian people said “enough.” That is one word Putin does not want to hear anytime soon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com