Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

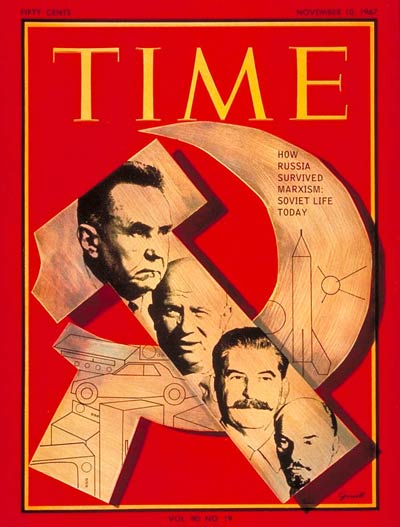

As Russia marked the 50th anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution that launched the Soviet Union on its way, TIME devoted a cover story to what was going on over there for America’s Cold War adversary.

While it was impossible to deny the progress made in realms such as science and industry, and the extent to which USSR-style communism had spread around the globe, it was also true that those gains had come at a cost — and that things were changing quickly. “Under the aegis of Premier Aleksei Nikolaevich Kosygin, 63, whose hound-dog countenance is better known in the West than the two or three others with whom he shares power, the government is experimenting with economic liberalization and cautiously widening the still narrow limits of individual freedom and expression,” TIME noted. “Ideology, long the great bugaboo of Soviet life, is being sacrificed to pragmatism in order to get things done.”

Which left the magazine with a few questions. Had the revolution “lived up to its own promise?” What were its effects on “the Russian character” and daily life there? How were the leaders doing, and what was their foreign policy?

The answer to the first question was relatively easy, as TIME saw it, as it would have been impossible to achieve the “restructuring of man himself” that the Bolsheviks had wanted. The second and third were harder, but as fear of Stalin-style repression faded, one historian pointed to a culture of “exasperation and contempt more than terror.” Quality of life was a mix, as citizens received free high-quality medical care and education, but lived in a nation where “for all its productive power, for all its feats in space… seems unable to produce a doorknob that always turns, a door that closes properly, a light fixture that works on the first try, a toilet that flushes consistently.” The fourth and fifth answers were summed up succinctly as there being too many cooks in the kitchen.

So what next? Though some theorized that communism and capitalism were converging into one master system of modern governance, TIME found that theory flawed. Which didn’t necessarily mean change wasn’t coming:

The men in the Kremlin possess power that is potentially limitless and unrestrained in its exercise; they could blow the whistle on reform any day and reimpose at least some of the tight discipline of the past. Once fully launched, however, liberalization may not be so easy to stop. The vast reorganization of the Soviet economy and the increasing force of technology are producing a second revolution in the habits and outlook of the people that the Kremlin will be hard-pressed to reverse. If that revolution continues to work its influence, arousing among Russians a longing to join the modern world and giving them a freer voice to articulate that longing, it could ultimately be of more significance than even the October Revolution.

And how was a story like this one framed for an American publication in the midst of the Cold War? The publisher’s letter at the front of the issue offers some insight — or, rather, anecdotal evidence of what can go wrong. Eastern Europe correspondent William Rademaekers made two trips to Russia for the story, the first booked through American travel resources and the second through a French agency, as he was applying for his visa while in Paris. On the first trip, nothing seemed amiss. On the second trip, Rademaekers — who did not speak French — was met at every turn by French-speaking official tourist guides and, more notably, found that all of the accommodations he had been provided were inferior to the ones from the first trip. The reason he was given, when he pressed for explanation, was one that might surprise observers focused on the political relationship between the U.S. and Russia. American tourists, he was told, are rewarded because they don’t complain about what things are like in Russia.

On fire: After a year of devastating wildfires in California, this look at another such season is poignant. In 1967, heavy rains in the spring had caused Southern California to be filled with lush vegetation, which a summer drought then turned into miles of kindling. The fires burned more than 100,000 acres and left 5,000 people homeless.

Jackie in Cambodia: Fulfilling an old dream of hers, Jacqueline Kennedy traveled to Cambodia to see Angkor Wat. Though she was not First Lady anymore, the U.S. government had high hopes that the warm reception she received would be a good sign for relations between the two nations, which were more than frosty. That hope, however, would not come to fruition in the years to follow.

Scotland speaks up: The election of Winifred Ewing to Britain’s Parliament was the first time a member of the Scottish National Party had gotten that far in more than 20 years. She advocated for Scottish independence by 1970 — and, though she wouldn’t get it, the idea remains in play a half-century later.

Secrets kept: As anti-war student protesters across the country tried to convince universities to stop taking government contracts for secret defense research, TIME’s education section looked at the arguments on both sides. Though the moral argument against that research was much louder, perhaps because those who disagreed were sworn to silence, some scientists were able to point out that, as one electrical engineer put it, “To know what is important in this field, you have to be in on the classified aspect of it.”

Great vintage ad: This ad for a rudimentary teach-by-television system provides a look at how a TV and a microphone could be used to broadcast interactive lectures to classrooms far and wide.

Coming up next week: African-Americans Run for Office—And Win

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com