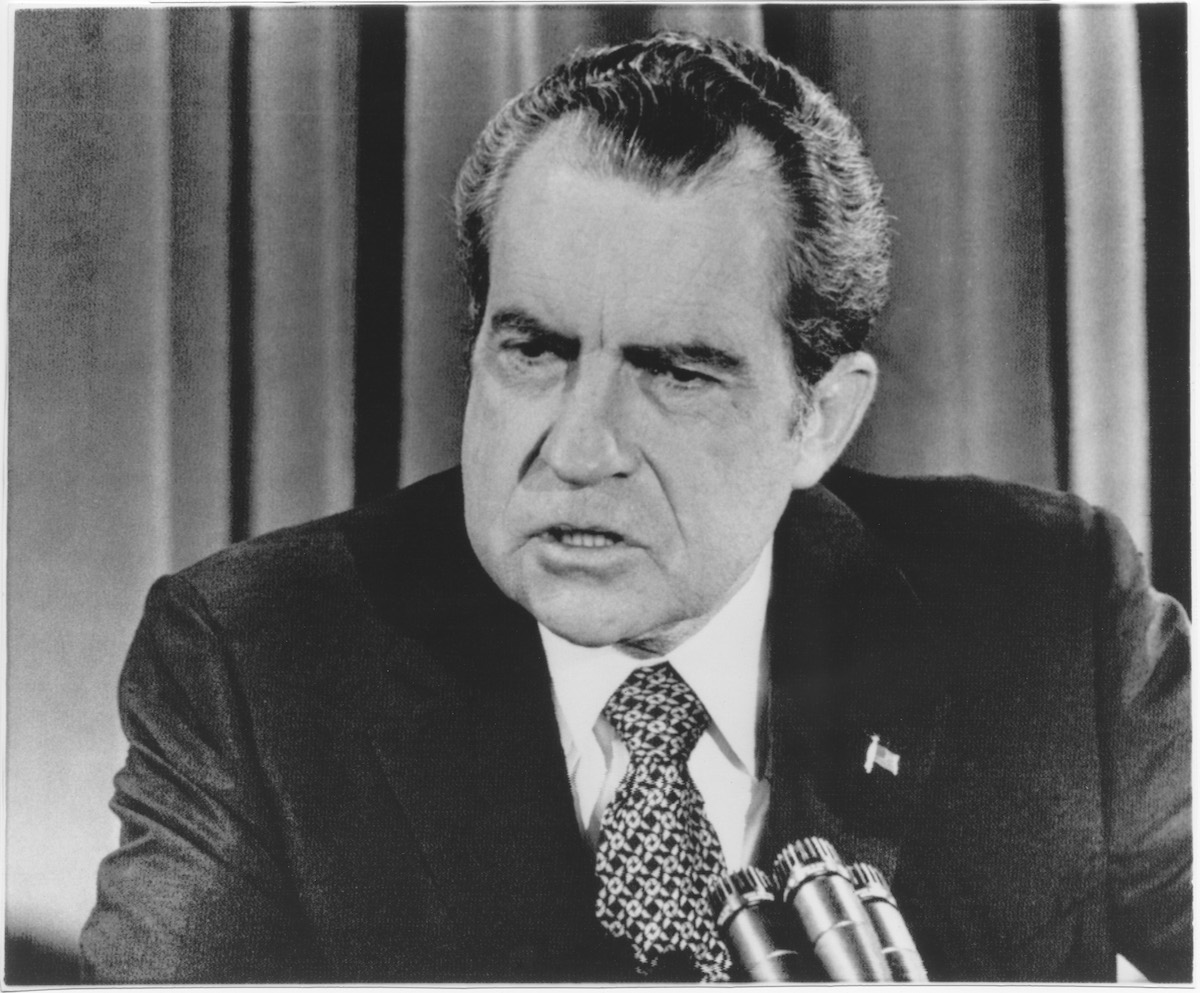

When Bob Woodward told Fox on Sunday that the firing of James Comey did not reach the gravity of Watergate, he explained that he meant that we did not yet know the extent of what might be going on at the White House. Yet the same was true during the whole summer and fall of 1972, when Woodward and Carl Bernstein made their names reporting on the links between the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), the White House and the burglary of the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate in June of that year.

Now, however, the echoes of later, more critical stages of Watergate have become unmistakable.

For one thing, there’s the matter of the memo. The critical Watergate memo of June 28, 1972 was written by General Vernon Walters, a military intelligence officer and linguist who had made his name as an interpreter during and after the Second World War. Walters had interpreted for Richard Nixon during his 1958 trip to Latin America, when he was twice assailed by angry mobs, and Nixon had made him the deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency, under Richard Helms. On June 23, just six days after five burglars had been arrested in the Watergate — but before White House and CREEP operatives E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy were arrested — Walters and Helms were summoned to meet Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman, at the White House.

Haldeman told Helms and Walters what he wanted them to do. “The investigation was leading to a lot of important people and this could get worse,” Walters reported. “Haldeman said the whole affair was getting embarrassing and it was the President’s wish that Walters call on Acting Director L. Patrick Gray and suggest to him that, since the five suspects had been arrested, this should be sufficient, and that it was not advantageous to have the inquiry pushed.”

Although Hunt and Liddy were in fact arrested and indicted, the Administration managed to keep the investigation away from the White House until after the election. And Walters’ account of this meeting, released in June 1973, was not enough to bring about the end of the Nixon presidency. But it was the tape of the conversations between Haldeman and Nixon before and after this meeting, in which Haldeman told Nixon how he was going to use the CIA to stop the investigation and then reported that all had gone well, that forced Nixon’s resignation 14 months later.

The Comey memorandum of his Feb. 13 conversation with President Trump seems to be at least as damning as the Walters one, since it reports that the President himself — just a day after Flynn resigned as National Security Adviser — expressed the hope that the FBI investigation of Michael Flynn’s ties to foreign governments would be stopped. Comey, like Walters, apparently made a written record of the meeting. “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go,” Trump told Mr. Comey, according to the memo.

Secondly, there are the firings. It did not take long, evidently, for President Trump to find that his thrust had been parried, and that Comey was not only continuing but expanding his investigation of links between Russian officials, the Trump campaign, and individuals now part of the Administration who had Russian contacts. Last week, President Trump dismissed Director Comey, an event that likewise drew Nixon-era comparisons.

By the spring of 1973, bipartisan political pressure had forced Nixon to appoint a special prosecutor. Nixon’s Attorney General, Elliot Richardson, was a liberal Republican from Massachusetts, who selected Harvard Professor and former Solicitor General Archibald Cox for the role. Cox hired a staff and went to work with a will. During the summer of 1973 came the revelation that Nixon had recorded his conversations in the Oval Office, and Cox promptly subpoenaed about half a dozen of those conversations. The White House refused to provide them, and Cox won a decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia. Rather than comply, Nixon’s legal team offered to give Cox transcripts of the conversations, authenticated by a third party. When Cox refused the compromise, Nixon order Richardson to fire him. Richardson refused and resigned. His deputy William Ruckelshaus also refused, and Nixon fired him. Acting Attorney General Robert Bork took over and fired Cox. Nixon also announced that the office of the Special Prosecutor had been abolished and that the investigation would go back inside the Justice Department. In response to the huge firestorm of opposition that followed, Nixon not only replaced Cox with Leon Jaworski, but agreed to release the subpoenaed tapes.

And, thirdly, just as Jaworski replaced Cox, another FBI Director, Robert Mueller, will now serve as a special counsel independent of the Justice Department. The Nixon precedent suggests that he has important things to discover.

The differences between the 1970s and today remain great, but given the striking similarities between the two situations, it should be possible for the nation — and the President — to learn from what happened back then.

We now know why Nixon had wanted to avoid releasing the tapes of his conversation. One tape in particular, of March 23, 1973, showed him deeply involved in a conspiracy to obstruct justice by paying off witnesses. And yet Nixon convinced himself that his guilt or innocence was irrelevant, and that Watergate was simply the last attempt by his enemies in the press and among the Democrats to do him in. He hung on to office for as long as he could, at great cost to the country. More than 40 years later, the scars of Watergate remain. The U.S. has not yet fully recovered the trust in government that was lost during that period.

We really have no idea exactly why Donald Trump wanted James Comey to halt his investigation of Flynn, and why he argues (as Nixon did) that the whole F.B.I. investigation is a waste of time and money. With Mueller in place, there is little for the public to do but wait. Not so for Trump. At some level, the President must know what Mueller might find, and whether his administration has in fact been compromised in some way.

If the answer is yes, let us hope that he will be willing to respond more gracefully and rapidly than Nixon did, even if that means departing the office. The final lesson of Watergate for those in the White House is that even the most powerful office in the world is not necessarily powerful enough to prevent the truth from coming out.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com