Imagine a President who is convinced that the media, the Washington bureaucracy (led by the State and Defense Departments), and the Washington D.C. establishment are completely against him and must be treated as enemies.

When the New York Times or the Washington Post prints a story he does not like, he orders his entire staff to avoid all contacts with their reporters until further notice. He attempts to centralize all power in the White House, particularly with respect to foreign affairs and defense policy, and often keeps his Secretary of State in ignorance of what diplomacy he is conducting. The President also has strong feelings about certain ethnic groups, which he vents in telephone calls to his staff. He does not trust the FBI to carry out critical national security investigations. He also has strong feelings about criminals, and at one point announces, in the middle of a celebrated murder trial, that the accused is guilty. He bluntly attacks judicial decisions with which he disagrees. In the evening, after long days of work, the president often records his feelings, railing again and again at the rich and famous who have always had it in for him. He is obsessed with the adulation showered upon his predecessor, who in the opinion at least of some of his faithful supporters was never rightfully entitled to the White House at all. Late in his first successful campaign for President, this man engaged in secret negotiations with a foreign nation that helped torpedo a diplomatic initiative that might have caused him to lose the election.

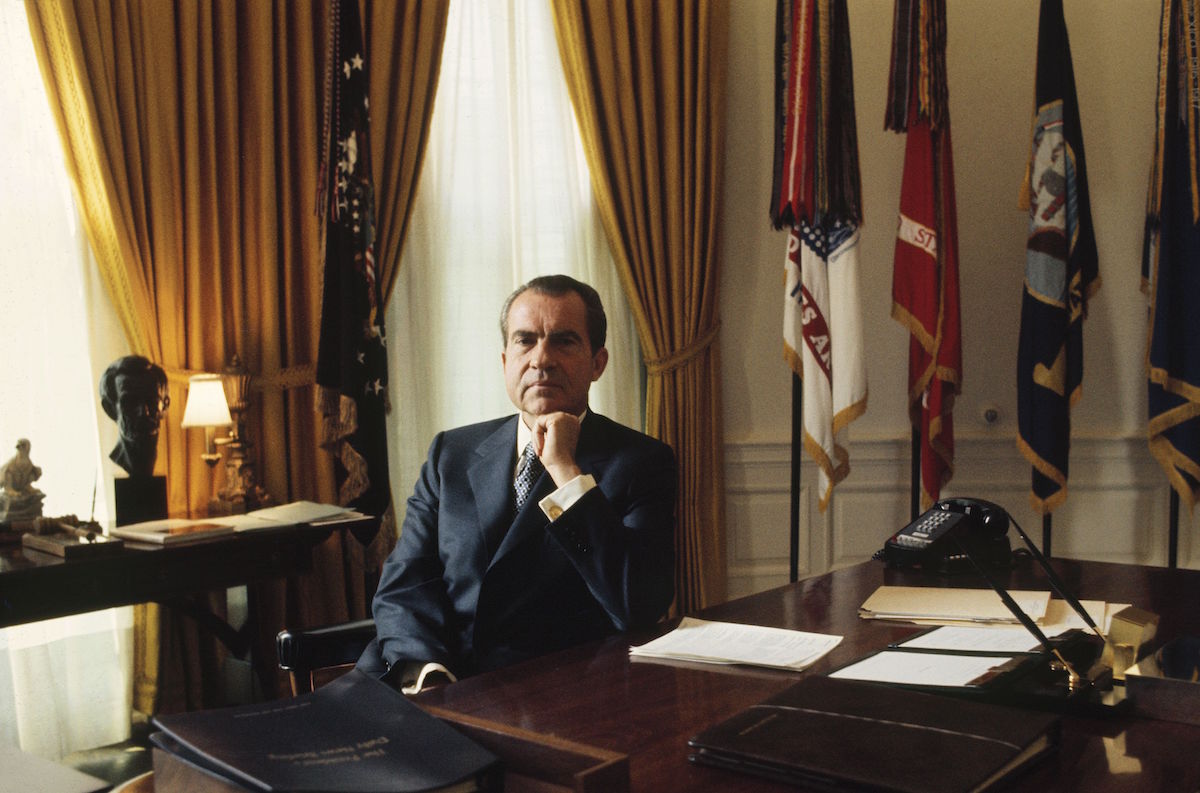

Six weeks into the Presidency of Donald Trump, readers will not be able to make it through that paragraph without a certain sense of déja vu. For example, Trump routinely attacks key federal agencies, including the FBI and CIA, and rushed through his first Executive Order restricting immigration without consulting key bureaucracies. But it is not about him. The President in question came from Trump’s parents’ generation, not his own. It was Richard Nixon.

Comparisons between Nixon and Trump are already numerous, from commentators ranging from Carl Bernstein to Stephen Colbert. The Late Show has even joked that Trump receives social-media counseling from Nixon’s ghost. But Nixon came from a different time and governed a very different America. Therefore, until the Watergate scandal really became critical in early 1973, Nixon’s presidency went very differently from the way Donald Trump’s has so far, reflecting key differences between that time and this one.

To begin with, despite the controversies over civil rights, urban riots, student revolts and the Vietnam War that dominated the late 1960s and early ’70s, the nation was still ruled by a bipartisan political establishment that agreed on the essentials of domestic and foreign policy. Nixon bowed to the views of that establishment when he began de-escalating the Vietnam War about a year into his presidency, and he also went along with big domestic changes with which he personally disagreed, such as the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The Congress also blocked some of his moves, such as his two attempts to put conservative white southerners with dubious qualifications onto the Supreme Court.

Nixon had some relatively extreme conservative views and prejudices, but he generally governed as a centrist because he really had no choice. And in foreign policy, at least as regards relations with the great Communist powers of the USSR and China, he stood slightly to the left of center, opening up relations with Beijing and reaching arms-control agreements with the USSR.

The nature of the times also led Nixon and his staff, critically, to keep his personal behavior under wraps. His staff obviously understood that they had to blow off many of his more extreme requests. For example, on one occasion documented in the HBO documentary Nixon in his Own Words, Nixon—using a religious slur in the process—demanded that an Immigration and Naturalization Service employee be removed from his job after the man announced a raid that had uncovered illegal immigrants in the employ of a Nixon campaign donor—but apparently nothing happened. Nixon’s orders to shut off major media outlets were often honored in the breach, as well. Even during Watergate, the staff—now reduced to a loyal remnant—refused his requests to leak damaging information about past administrations to the press. Although in secret, Nixon’s paranoia eventually led to the Watergate break-in and the cover-up that destroyed his presidency, in public, everyone understood that a President simply could not give vent to his deepest, bitterest thoughts. (Lyndon Johnson and his staff had known this too, and Johnson’s earlier knee-jerk accusations that reporters who wrote damaging stories were “Communists” did not come to light for many years either.)

For several decades now, however, we have celebrated outrageous behavior, and now anyone from the President to the average citizen can broadcast his spontaneous thoughts and feelings to the entire world with a few keystrokes. It took years for the content of the Nixon tapes to become public but, thanks to Twitter, President Trump’s ideas can be conveyed instantaneously. And those tweets, in addition to giving vent to the President’s thoughts, can also distract the media from other problems in the administration in a way that Nixon might envy.

Trump has already expressed contempt for court decisions and raised questions about his conception of executive powers. If he does exceed his constitutional powers, alas, the chances of the other branches of government restraining or removing him, as they did with Nixon, are not as good. Trump, unlike Nixon, is dealing with friendly majorities in both houses of Congress. The Democrats in 1973-4 combined partisan feeling with civic virtue, and enough Republicans eventually joined with them to ensure Nixon’s removal from office. So far nearly all of today’s Congressional Republicans have gone along with the Trump White House’s ideas and oppose broad inquiries into his campaign’s possible wrongdoing. Meanwhile, Trump’s unrestrained campaign rhetoric has continued apace now that he’s in the White House, showing that the U.S. is in a perilous state. The abuse of free speech may be a right, but it is also a grave danger.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com