Queen Elizabeth II, the world’s longest-serving head of state who led her subjects for more than seven decades, has died at the age of 96.

Her extraordinary reign, which began in 1952, spanned 15 British prime ministers and 14 U.S. presidents. She inherited the throne of a country almost broken by the legacy of war, and remained upon it through a time of epochal change both for the U.K. and the world.

The Queen had taken a step back from some royal duties in the months leading up to her death, including missing the State Opening of Parliament in May and the thanksgiving service at St. Paul’s Cathedral during the celebration of her Platinum Jubilee in June. Although the Queen was well enough to preside over the appointment of Liz Truss as Britain’s Prime Minister on Tuesday, she had to do so from her Balmoral estate in Scotland instead of Buckingham Palace, where such appointments are traditionally done.

The news of the monarch’s deterioration on Thursday was quickly followed by reports that her family, including her son Prince Charles and grandsons, Prince William and Prince Harry, had gathered in Balmoral to be with her.

The Queen had remained a stoic, almost timeless figure in the public’s eye, carrying out her royal duties despite the inconvenience of advancing age and when her private life was in turmoil.

When Elizabeth took the throne, the U.K. was the seat of an Empire that straddled the globe. Today, Britain is a smaller player on the world’s stage, but the Queen remained the sovereign leader of 15 nations—including Australia, Canada, and New Zealand—and head of a Commonwealth of more than 50 nations. She traveled the globe as an ambassador for British achievements, acts of charity, and values. She was also devoted to upholding the “special relationship” between the U.K. and the U.S., engaging with every president from Harry Truman to Joe Biden over a period of more than 70 years.

The world changed while Elizabeth was Queen in profound ways, but many saw her as a steadfast rock of patriotic duty. As her grandson Prince William wrote in the preface to a 2015 biography: “I think I speak for my generation when I say that the example and continuity provided by the Queen is not only very rare among leaders but a great source of pride and reassurance … I am privileged to have the Queen as a model for a life of service to the public.”

Born an heiress

Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor was born by cesarean section at 2:40 a.m. on Apr. 21, 1926. She was an heir to the throne, but third in the line of succession. Her father, Prince Albert—”Bertie” to friends and family—was the second son of the reigning monarch, King George V. His older brother, David, known by his royal appellation Edward of Wales, was first in line to the throne. But he was also single, childless, and already rumored to have little interest in inheriting his father’s crown and the duties that went with it.

The early life of Princess Elizabeth was chronicled with zeal both by the British press and in the former colonies. “The water was from the River Jordan,” TIME reported of the elaborate christening pageantry staged in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. Sir Winston Churchill first met Elizabeth at Balmoral Castle in 1928, when she was two, and proclaimed that he saw in her “an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.”

No one in all the realm was more enamored with the young Elizabeth than its monarch, who gave her the place of honor on his lap when they rode through the streets of London in his royal stretch Daimler. “No one else except the Queen rides out so often with the king,” TIME reported. Left, not ungladly, out of the spotlight was Lilibet’s father—the ever-reticent in public, self-deprecating Bertie, who once told reporters, “My chief claim to fame seems to be that I am the father of Princess Elizabeth.”

Her reign as only child ended at age four, in 1930, with the birth of her sister, Margaret Rose, at Glamis Castle in Scotland, their mother’s ancestral home. The girls romped together on the palace grounds and royal country estates, played with their terrier puppies and corgis—Elizabeth’s lifelong favorite. They also stabled, cared for, and learned to train a royal succession of pet ponies, and shared the same nannies and governesses.

In January 1936, upon the death of Lilibet’s grandfather George V, her uncle David became King Edward VIII. Almost immediately, his eldest niece and all the royal family became prime players in a 20th-century succession drama that, though bloodless, proved riveting to a worldwide audience. Edward’s tumultuous 10-month reign as king ended on Dec. 10, 1936, when he scandalized the world by abdicating the throne to marry the twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Warfield Simpson. “I always told those idiots not to put me in a golden frame,” he said. Young Lilibet was only 10 when she learned she would one day become queen after her father’s death.

Princess in wartime

Elizabeth was barely a teenager when, on Sept. 3, 1939, Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. The war’s threat had already thundered throughout Europe, and soon the kingdom Elizabeth would one day rule, along with much of the rest of the world, was engulfed in war. Less than a year later, Hitler entered Paris and promised to make Britain his next conquest. Soon the Blitz—day and night Luftwaffe bombing raids that rained fire and terror over London, Liverpool, and other cities throughout England—was at full roar.

And so the Princess spent her teens knitting socks for British soldiers, collecting tinfoil, and rolling bandages for the war effort. She would send portions of her five-shilling weekly allowance to emergency child welfare funds, wear secondhand clothes, adhere to the war rations diet dictated for all Britons, and live frugally despite being a teenage princess and heir to the British throne.

Even as bombs fell on Buckingham Palace—it was hit nine times, including once in September 1940, but the King and Queen managed to escape unharmed—the royal couple refused entreaties to abandon London and evacuate Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret to Canada. “The children won’t go without me,” said the Queen. “I won’t leave without the King. And the King will never leave.”

The King’s decision to remain in England for the duration of the war, enduring its deprivations along with his subjects, endeared him to the beleaguered nation. But it also made the likelihood that Elizabeth might suddenly be called to the throne in the event of her father’s death seem palpable.

The future monarch began her public life with her first live BBC radio broadcast in October 1940. Displaying poise and pluck, she addressed the tens of thousands of children who were evacuated from their homes and separated from their families at the height of the Blitz. “My sister, Margaret Rose, and I feel so much for you as we know from experience what it means to be away from those we love most of all,” she said in a clear voice that offered a hint of the calm and compassion that many would come to admire.

When in 1944 she reached military age at 18, Elizabeth joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service, one of the wartime women’s units. She spent three weeks at the Mechanical Transport Training Center, where she trained as a mechanic and truck driver. The labor left her covered in grease and grime and not a little well-earned pride. “Everything I learnt was new to me—all the oddities of the insides of a car,” she told a friend. “I’ve never worked so hard in my life!”

And she never partied so hard as she did a fortnight after her 19th birthday when, on May 8, 1945—Victory in Europe Day—she joined the ecstatic and rowdy street celebrations that swept London following Germany’s surrender. After standing in uniform on the balcony at Buckingham Palace to greet cheering crowds alongside the King, Queen, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, she, her sister, a group of friends, and a few guardians linked arms and ran among the crowds that surged through the city. For two nights in a row she “walked simply miles,” she wrote in her journal, “ate, partied, bed 3am!” These were, she would say 40 years later, among “the most memorable nights of my life.”

Royal wedding

It wasn’t long after the war that the young princess turned her mind to thoughts of marriage. Years before, Elizabeth had visited a naval college at Dartmouth where she had been greeted by a towering 18-year-old cadet.

Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark was born on the Greek island of Corfu on Jun. 10, 1921, nephew of King Constantine of Greece and distant relation to Britain’s Queen Victoria. As his family drifted apart he was sent, at the age of nine, off to England to live with his grandmother, the widow of the great British naval commander and German prince Louis Alexander Mountbatten. He was schooled in England, Germany, and Scotland, and became a fine young athlete—as Elizabeth would note to her governess, Crawfie, on that trip to Dartmouth: “How good he is, Crawfie. How high can he jump!”

Elizabeth corresponded with Philip throughout the war, and after its end the prince was placed on shore duty at a naval base on England’s south coast. He often made the 100-mile trek to London in his small black MG, frequently stopping at Buckingham Palace to have dinner with Elizabeth and her younger sister, Margaret. Their friendship grew into a romance. Elizabeth was delighted. Her father George? Not so much—at first. “His loud, boisterous laugh and his blunt, seagoing manners…irritated the gentle king,” TIME reported in 1957. Despite that chill, Elizabeth and Philip decided to marry after a short stay with her family at Balmoral Castle in the summer of 1946. The king’s lack of enthusiasm for Elizabeth’s beau—an attitude sparked, in part, by his concern over how the people of Britain would take to a foreign-born prince marrying the heiress to the throne—frustrated the princess. “There was many a tense moment for George as Elizabeth moped about in tearful martyrdom while her mother and grandmother, the doughty old Queen Mary, fought her battle for her. At last, George decided that the young couple (she was 20, he 25) should wait six months to make sure of each other,” noted TIME.

There were obstacles to overcome, but none insurmountable. Philip became a British citizen, and public opinion polls showed that a majority of the nation’s populace favored his marrying the princess. The official announcement did not come until Jul. 9, 1947, followed by the couple’s introduction at a Buckingham Palace garden party. The wedding took place that November, on the 20th. Philip had converted from Greek Orthodoxy to Anglicanism, avoiding one social problem before the ceremony, and Elizabeth’s father made the former member of the Greek and Danish royal families a British royal duke, the Duke of Edinburgh, to be called His Royal Highness, or simply Prince Philip.

As Elizabeth made her way to Westminster Abbey in the royal coach on her wedding day, thousands cheered from the neighboring sidewalks of London. Celebrations erupted throughout the globe, from Paris to Panama, from Shanghai to Manhattan—where thousands got out of bed at 6 a.m. to listen to the ceremony broadcast on the radio. Dignitaries—five kings, six queens, Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill—were in attendance. All of Britain celebrated, many seeing the wedding as a beacon of hope in the post-World War II recovery period.

The Coronation

On Feb. 5, 1952, Princess Elizabeth went to bed in a tree hut nestled in Kenya’s Aberdare National Park and awoke the next day as the Queen of England. She was unaware of her new position, for news of the death of her father, King George VI, had not yet reached that outpost of the British Empire. That afternoon, at a lodge, Philip received a phone call informing him of George’s death. The prince took his bride down to a nearby river’s edge and relayed the news. Shaken, but in full command of herself, Elizabeth returned to the lodge on Philip’s arm and began making arrangements for the long trip home.

Elizabeth arrived at London’s airport the following morning. Churchill was there to greet her, along with a small group of privy councilors—advisers to the monarchy. That night she rested; the next day she signed the oath of accession before the Privy Council, and an hour later her accession was formally proclaimed. In the months that followed, there was no hurry to arrange her formal coronation—she was already, technically, the Queen. So Elizabeth and the Palace allowed the focus to stay on King George and his 16 enormously popular years on the throne, and let the nation’s sadness ebb.

The official ceremony finally took place on Jun. 2, 1953, a day chosen in hopes of sunny spring weather. This being London, however, the nation settled for a traditional gray morning. At 11 a.m., a joyous fanfare of trumpets announced the arrival of Her Majesty. “Vivat Regina Elizabetha! Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!” shouted the Queen’s Westminster Scholars as she walked up the aisle, her long crimson train borne by six maids of honor. The Archbishop of Canterbury proceeded to ask Elizabeth if she would govern her people according to their laws and customs, execute law and justice in mercy, and maintain the laws of God. She knelt, kissed the Holy Bible before her, and swore to do so, “so help me God.” Finally, he held aloft the Imperial State Crown for all to see, then placed it on Elizabeth’s head. Cheers of “God Save the Queen” filled the Abbey as trumpets blared; outside, and across the British Empire, bells pealed and cannons roared.

The traveling Queen

As well as the constitutional duties Elizabeth fulfilled as Britain’s head of state and the head of the Church of England, she spent long sections of the following decades traveling the world as her nation’s goodwill ambassador. The November after her coronation she embarked on a 45,000-mile tour of the British Commonwealth, presiding over state balls, garden parties, luncheons, banquets, and other occasions. Among her stops: Libya, Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Jamaica, Uganda, and the Pacific island of Tonga, where she enjoyed the company of Queen Salote Tupou, who had traveled to London months before to witness Elizabeth’s coronation. She did not return to London until May 15, 1954, almost six months after she departed.

In the fall of 1957, Elizabeth and Philip spent six days in New York City, Washington, D.C., and parts of Virginia, where they celebrated the 350th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, the first British colony in America. In Washington, they were guests of President Dwight D. Eisenhower—a friend since his days in London as Supreme Allied Commander during World War II—for four nights at the White House. At the president’s state dinner, Elizabeth praised Washington as “so often a focus for the aspirations of the free world.” Later, Vice President Richard Nixon hosted a luncheon at the Capitol, and Elizabeth sought to see how the average American enjoyed life, attending a football game at the University of Maryland and stopping in a Giant supermarket after the game.

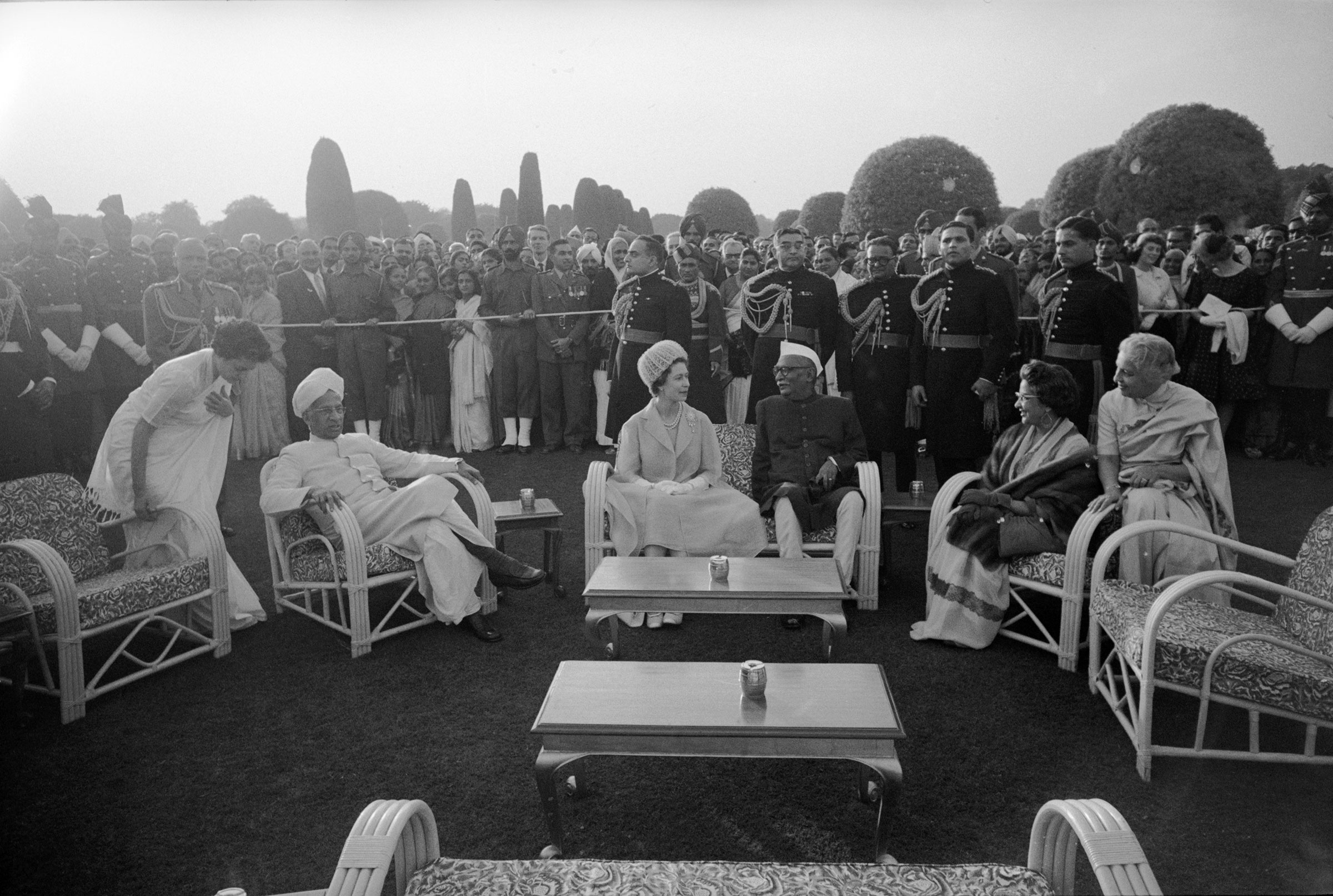

Clearly, the travel bug had bitten. In 1961, Elizabeth visited India, and at the Ramlila Grounds near Old Delhi, a quarter of a million people came to see her speak. In the city of Jaipur, the Maharajah offered her a ride on a ceremonial elephant. Though the trip was a success for Elizabeth, it also put the Indian government on edge—they viewed such a display of colonial pageantry as undermining the country’s fledgling independence. Philip also drew negative publicity when official photos emerged of a tiger he’d killed on a hunt with the Maharaja. An Indian government spokesperson called the act “astonishing,” while the British tabloid The Daily Mirror condemned the royals for not recognizing “the modern enlightened view on the killing of animals for pleasure.”

In Ghana that same year, Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah told the Queen, “The wind of change blowing through Africa has become a hurricane.” (Ghana had declared independence from the British Empire in 1957, though the legacy of colonialism still hangs over the country.) Tanzania would declare independence later that year, joined by Kenya in 1962, and a series of other African nations throughout the 1960s.

In 1965, Elizabeth embarked on an 11-day tour of West Germany, the first state visit by a reigning British monarch since Edward VII paid his last call on Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1909. The trip came a full two decades after the end of World War II, amid fears of lingering resentment between the U.K. and Germany. But those fears were misplaced. The Queen and German chancellor Ludwig Erhard said all hostility between their countries had been healed in the 20 years since the war. It ended in triumph, with crowds cheering and chanting “Elizabet, Eliz-a-bet!” as she placed a wreath on a Beethoven monument near the Bonn city hall.

Family trouble

All that traveling would put a strain on her family. That five-and-a-half-month world tour following her coronation took place when Charles was five and Anne only three—but the children were left behind. They did chat with their traveling mother by radiotelephone. But this would go on to be characteristic of Elizabeth, who always tended to make work her priority.

Years later, in 1994, Prince Charles would allow his authorized biographer to disclose that the prince felt “emotionally estranged” from his parents, who were “unable or unwilling” to offer the affection he craved as a young man. Close friends found the Duke’s behavior “inexplicably harsh” and called his manner toward Charles “very bullying.” His mother, the Queen, seemed “detached.” Elizabeth and Philip were reported to be hurt by this disclosure. Publicly, only Philip would comment, “We did our best.” But Princess Anne, the couple’s daughter and Charles’s younger sister, exercised less restraint—and in the process defended Elizabeth from rumors that she was remote and uncaring as a mother. “I simply don’t believe that there is any evidence whatsoever to suggest that she wasn’t caring,” she said in 2002. “It just beggars belief. We as children may have not been too demanding, in the sense that we understood what the limitations were in time and the responsibilities placed on her as monarch in the things she had to do and the travels she had to make. But I don’t believe that any of us, for a second, thought she didn’t care for us in exactly the same way as any other mother did.”

Yet even Anne might have acknowledged a warmth that was sometimes wanting on her part later in life—when a little more compassion, a little more kindness, might have been called for.

The early 1990s would bring all kinds of personal problems to the fore—most notably in 1992, which the Queen famously described in a speech as an “annus horribilis” (horrible year). This was the year when her second son, Andrew, separated from his wife, Sarah; when daughter Anne divorced her husband, Mark Phillips; when her son Charles and his wife, Diana, increasingly became a tabloid issue; and when public concern grew about the cost of the monarchy and who would pay to repair Windsor castle, which caught on fire that year.

The damage was significant. The Nov. 20 fire—on the Queen’s 45th wedding anniversary—gutted the northeast corner of the castle, parts of which were more than 900 years old. It took 250 firefighters 15 hours to bring it under control. The state apartments, used for high-level official entertaining, did not have a sprinkler system, and in the end more than 100 rooms, covering an area of 1.7 acres, were damaged.

When British citizens learned that they were about to foot the bill for repairs to Windsor Castle—to the tune of up to $78 million—they grumbled. Elizabeth rectified the issue by volunteering to pay income and capital gains tax from her private investments. It hurt, but not too much: Her net worth remained at about $500 million.

But these were simply matters of state. It was matters of the heart that caused greater grief for Elizabeth—particularly the travails of Charles and Di.

Their courtship and 1981 marriage captivated the nation, if not the world. No less an authority than the Archbishop of Canterbury proclaimed, “Here is the stuff of which fairy tales are made: the prince and princess on their wedding day.” But infidelity would intrude on both sides, and the ability to maintain even the pretense of marriage for the sake of appearances became impossible. On Aug. 24, 1992, the transcript of a phone conversation between Diana and a close friend was published in The Sun tabloid, with Diana describing life with Charles as “real torture,” and saying she had caught the Queen Mother watching her “with a strange look in her eyes.” Diana and her young sons, William and Harry, continued to reside at Kensington Palace, while Charles’s relationship with Camilla Parker Bowles was parsed by the tabloid press. The Prince and Princess of Wales officially separated on Dec. 9.

Diana’s decision to grant an interview to the BBC on Nov. 20, 1995, in which she confessed that she had been unfaithful to Charles, had upset the royal family and Queen Elizabeth in particular. (Of course, Charles had admitted his own infidelity on a TV documentary the previous year, as Diana noted in the interview, referring to Camilla Parker Bowles, “There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded.”) Within a month, the Queen wrote to both Charles and Diana, urging them to agree to an early divorce. Buckingham Palace released a statement saying Charles favored the divorce, but there was no official word from Diana. In February 1996—more than a year before Diana, her romantic partner Dodi Fayed, and driver Henri Paul died in a car crash while being pursued by the paparazzi—she finally released her own statement saying she was ready to divorce too. Elizabeth’s reaction? “The Queen was most interested to hear that the Princess of Wales had agreed to the divorce,” was all her press office would say at first. Later, it would announce that the Queen wished the divorce discussions “be conducted privately and amicably.”

It took time for Elizabeth—a woman married seven decades to the same man—to adjust to modern mores. A longtime sticking point was Charles’s future bride, Camilla; the press noted that Elizabeth was not enamored of her son’s consort. The turning point occurred in 2002, when, by bringing Camilla to events celebrating Elizabeth’s 50 years on the throne, Charles provided strong evidence that he was gaining ground in his campaign to officially bring Camilla into the family fold.

Charles and Camilla got engaged around Christmas 2004, and before long the Queen issued a statement saying, “The Duke of Edinburgh and I are very happy that the Prince of Wales and Mrs. Parker Bowles are to marry.” She and Prince Philip did not attend their wedding at Windsor Guildhall on April 9, 2005, but they did attend a blessing of the couple at St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle and held a reception for them at the castle.

A more festive wedding—and one more in keeping with Elizabeth’s sense of royal tradition—took place on Apr. 29, 2011, when Elizabeth’s grandson William married Kate Middleton in a lavish ceremony at Westminster Abbey. And she remained her regal self at Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s more modern wedding at Windsor Castle in 2018, which included a fiery sermon delivered by Bishop Michael Curry of Chicago, the first African American head of the Episcopal Church in the U.S.

The Queen would face further familial scandals, however. In a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey in March 2021, Harry and Megan alleged that racism had tarnished their relationship with the Windsors. While the press hounded Megan like they did Harry’s late mother, “no one from my family ever said anything,” Harry said.

The family was once again thrust into the spotlight when allegations surfaced about Andrew’s relationship with the late sex offender, Jeffrey Epstein. Andrew stepped back from royal duties in late 2019, and in 2021 was served with a lawsuit by Virgina Giuffre, one of Epstein’s victims, who accused Andrew of sexual abusing her when she was 17. According to The Daily Telegraph, the Queen contributed millions of pounds to her son’s legal defense, and agreed to contribute £2 million ($2.7 million) to a victim support charity as part of the eventual settlement.

As the Queen neared the end of her life, she doted more on her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. “In a small room with close members of the family, then she is just a normal grandmother. Very relaxed,” Harry said before he and Meghan stepped back as working royals in early 2020. “She obviously takes a huge interest in what we all do, that’s her children as well as her grandchildren. She wants to know which charities we’re supporting, how life is going in our jobs and such. So you know, she has a vested interest in what we do.”

Royal Duty

Even after she entered her ninth decade, Elizabeth continued with her royal duties, despite her age and a rapidly changing world.

For nearly all her reign, the Queen would read a selection of the 200 to 300 letters that she received daily, as well as review official papers and documents sent her way from government ministers and her representatives in foreign countries. Until she was forced to slow down by mobility issues and bouts of ill health, she would have 10- to 20-minute audiences with ambassadors, commissioners, and other officials, and there would be her weekly visit from the British prime minister.

Despite growing republican movements within the Commonwealth realms, the Queen herself remained a hugely popular figure in both the U.K. and beyond. And she remained a force for good, offering messages of inspiration and optimism in even the most trying times. In one of her last annual Christmas Day messages, she urged her subjects in Britain and across the Commonwealth to draw inspiration from “ordinary people doing extraordinary things.”

The Queen has been a constant figure in most of the British public’s living memory—in February 2022 she became the first British monarch to reach 70 years on the throne. Although mobility issues prevented her from attending the majority of Buckingham Palace’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations in June of the same year, community celebrations were widespread across the U.K. Some 16,000 official street parties were organized and almost 17 million people—about one in four Brits—took part in events. The Together Coalition, which aims to bridge divides, said the celebrations were the largest community event in British history.

The Queen also looked extraordinary yet ordinary at Prince Philip’s funeral held shortly after he died on Apr. 9, 2021, after 73 years of marriage. The image of the monarch solemnly sitting alone in a pew at Windsor Castle due to coronavirus restrictions became instantly iconic, and further burnished her image as a stoic leader through good times and bad.

The Queen did not lead an ordinary life, but she filled it with extraordinary acts of duty both public and private—whether carrying out the requirements of the state from the trappings of the throne, or giving quiet words of encouragement to a well-wisher in a crowd. She “has been a rock of stability in an era in which our country has changed so much,” said Britain’s former Prime Minister David Cameron. “And we could not be more proud of her. She has served this country with unerring grace, dignity, and decency.”

—With reporting by Eloise Barry, Kathy Ehrich Dowd, Madeline Roache and Yasmeen Serhan

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com