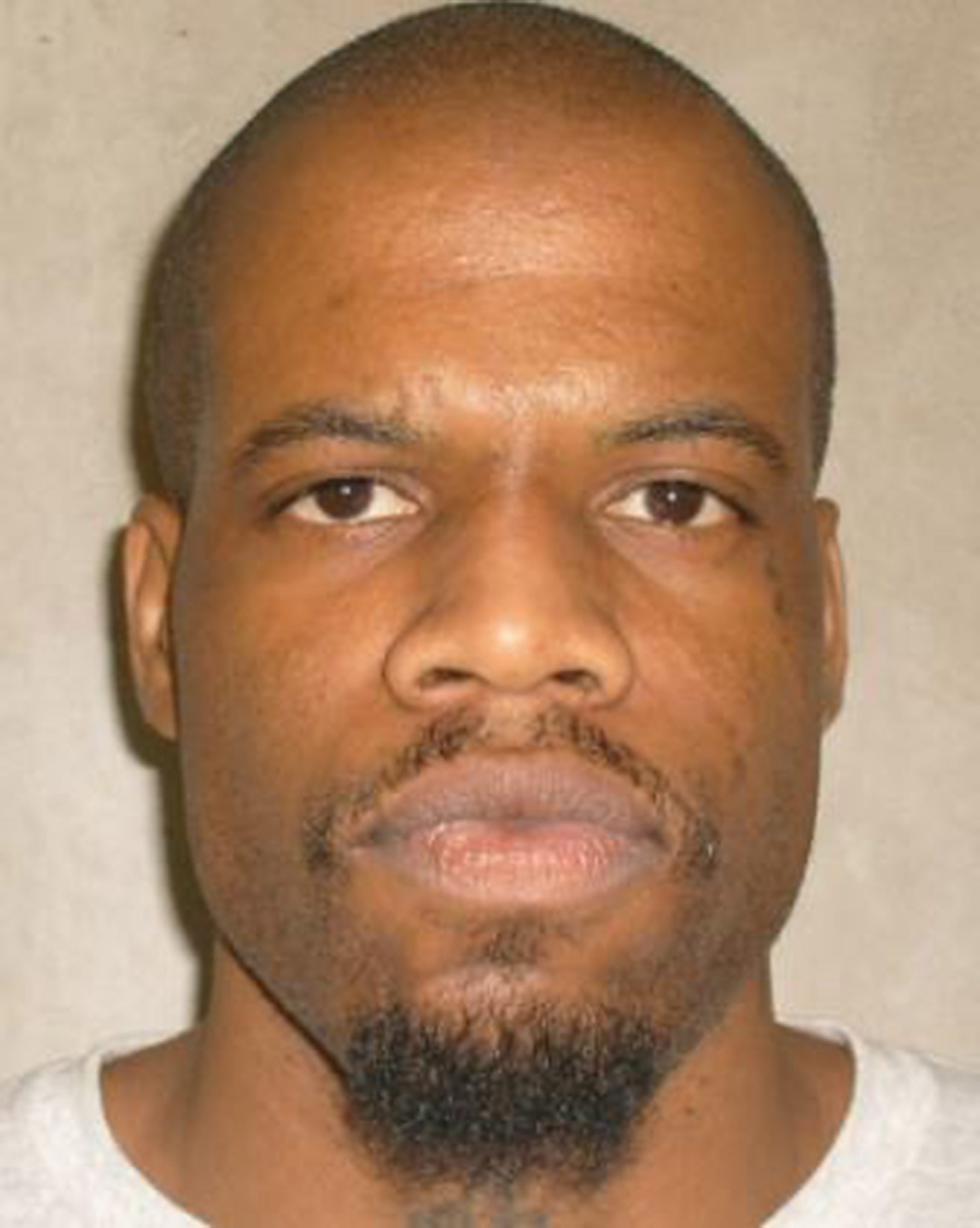

A little after 6:40 p.m. on Tuesday, Oklahoma Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton entered the viewing room of the state penitentiary’s lethal injection chamber and announced that a stay of execution had been issued for death row inmate Clayton Lockett, who was then on the other side of a lowered beige curtain writhing and twitching from the drugs entering his veins.

The announcement surprised those watching the execution from behind the glass window.

“My impression was, my God, they’re going to try to save this poor guy so they can kill him later,” says Dean Sanderford, one of Lockett’s attorneys. Sanderford and his co-counsel David Autry were asked to leave the viewing room, believing Lockett would be revived and executed at a later date. At 7:06 p.m., the D.O.C. announced that Lockett had died of a heart attack.

Exactly what happened in those 25 minutes is known only to the prison officials inside the execution chamber. The attorneys were told to leave the viewing room. A few reporters stayed behind, but the curtain remained drawn and their view was blocked. However, some facts are not in dispute. Lockett, a convicted murderer, was injected with an untested blend of drugs obtained from an undisclosed source. Lockett had been declared unconscious after an examination by an attending physician, only to then start moving his body, rolling his head from side to side and mumbling, according to Tulsa World editor Ziva Branstetter, who observed the execution.

The question of just what went wrong in Lockett’s execution, the latest in a series of recent state-sanctioned killings that have not gone as planned, has fueled a renewed debate over the use of lethal injection in the United States. On Wednesday, the White House implied that Lockett’s protracted death may have violated the ban on cruel and unusual punishment established in the Eight Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

“We have a fundamental standard in this country that even when the death penalty is justified, it must be carried out humanely,” said Jay Carney, President Obama’s press secretary. “And I think everyone would recognize that this case fell short of that standard.”

(Read More: America’s Long and Grisly Search for the Perfect Way to Kill)

Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin on Wednesday announced an investigation into what went wrong as well as a 14-day stay of another execution that had been scheduled for that same day, while vigorously defending the state’s right to administer capital punishment.

“I believe that the death penalty is an appropriate punishment for those who commit heinous crimes against their fellow men and women,” Fallin said. “However, I also believe that the state needs to be certain that its protocols and procedures for executions work.”

Lockett’s attorneys believe that it did not and they are planning to pursue legal recourse.

“We have not yet determined what those will be,” Seth Day, a member of Lockett’s defense team, told TIME, “only that there will be a legal action.”

Oklahoma corrections officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The fight over the application of the death penalty in the U.S. has been revived by a spate of executions that have gone awry since states began experimenting with different drug combinations after being unable to obtain more standard lethal injection drugs.

On Jan. 9, Michael Lee Wilson, who was convicted of murdering a convenience store clerk, declared he “felt his whole body burning” after Oklahoma administered a combination of pentobarbital, vecuronium bromide to stop respiration and potassium chloride to stop the heart. A week later, Dennis McGuire, who was sentenced to die for raping and killing a 22-year-old pregnant woman, thrashed and snorted before finally succumbing after about 25 minutes following Ohio’s use of a new lethal drug mix. McGuire’s family is now suing Hospira, a pharmaceutical company, for providing the state with execution drugs. Ohio said this week that its review found McGuire’s execution was “conducted in a constitutional manner,” but that it was increasing drug dosages in future executions.

Death penalty opponents and critics of the current system of lethal injection are trying to use these bungled executions to build a case against the constitutionality of the method while shedding light on the increasingly murky details surrounding it. Oklahoma has been at the center of the debate since January, when Lockett and another death row inmate, Charles Warner, sued the state over a law that shields the source of drugs used in lethal injections.

(Read More: Every Execution in U.S. History in a Single Chart)

Numerous states have passed similar laws as a way to protect drug suppliers from boycotts and other political backlash. As commercial pharmaceutical companies increasingly refuse to allow their products to be used in executions, states have turned to compounding pharmacies for their supply. These pharmacies, which mix drugs to order, are not regulated by the federal government. A 2012 meningitis outbreak that killed 64 people was linked to a contaminated supply from one compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts.

Capital punishment opponents have challenged these secrecy laws on the grounds that sub-standard drugs from anonymous suppliers are more likely to lead to botched executions. Courts have rejected their arguments in many states. It surely doesn’t help their cause that many of the condemned have been convicted of horrific crimes. Lockett was sentenced to death for kidnapping and assaulting a 19-year-old woman and ordering an accomplice to bury her alive, while Warner was convicted of raping and murdering an 11-month-old.

After a messy, months-long legal fight that included a standoff between Fallin and the Oklahoma Supreme Court, the state’s secrecy law was ruled constitutional, and Lockett and Warner’s execution dates were officially set for Tuesday. Lockett’s lawyers hadn’t seen their client all day until they were seated in the execution chamber’s viewing room and prison officials lifted the curtain. There, on the other side of the glass, Lockett was strapped down on a gurney, covered in a sheet and surrounded by the warden, a physician and prison guards. They asked Lockett if he had any final words. He said no, and the warden signaled for the execution to begin.

Sanderford says that Lockett became visibly drowsy and that his eyes glazed over. It appeared that midazolam – a sedative meant to put Lockett to sleep – was beginning to take effect. The doctor came over to see whether Lockett was still conscious. He said he was, so they waited a few more minutes.

“At that point, the warden says in this formal tone, ‘Mr. Lockett is now unconscious,’” Sanderford says. “I took that as a cue to the executioners to start with the second and third drug.”

A couple more minutes passed, and that’s when things started going horribly wrong.

“It was almost subtle at first,” Sanderford says. “He started writhing and twitching, and then the writhing and twitching just got stronger and more violent. It looked like he was trying to lift his whole upper body off the table, as if he was trying to sit up. He was mumbling things that were clearly words but I couldn’t understand. His eyes opened at one point. It was the most gruesome spectacle I’ve ever seen in my life.”

A few minutes into Lockett’s jostling, the warden had the curtain lowered in the viewing room and the audio feed from the chamber cut. Sanderford says he could see shadows moving behind the curtain but couldn’t tell what was going on. At that point, several department of corrections officials began using a phone located in the visiting room.

“They kept pulling the cord outside the door and shutting the door so we couldn’t hear what they were saying,” Sanderford says. “They kept calling one guy out, calling another guy out. It was f—king chaos. They knew something was going wrong.”

Sanderford and Autry were told that a stay had been issued for both Lockett and Warner, who was scheduled to be executed later that evening. The lawyers said they were ordered to leave the visiting room and later to leave the prison grounds altogether.

At 7:06 p.m., prison officials announced Lockett had died of a heart attack and said that “the line had blown,” indicating that there was a problem administering the drugs into Lockett’s veins.

While it’s unclear what exactly happened inside the chamber, medical and legal experts attribute the prolonged death to a combination of incorrect dosage and inadequate training of the corrections personnel administering it.

Midzolam, the first drug used, was intended to put Lockett to sleep. He was given 100 mgs of it, according to Autry, one-fifth the dosage used in Florida, the only other state to use midazolam in a lethal three-drug combination.

“The takeaway I had was the so-called anesthetic agent was totally ineffective,” Autry says. “It was evident to me that he was not completely unconscious and he was going through a great deal of pain because he was visibly struggling throughout the process.”

Prison officials told reporters that there was a vein failure, but Sanderford believes it may have been an error on the part of those administering the drugs. At one point, a physician did declare Lockett unconscious.

“I think they screwed up putting it in or it somehow came loose during the procedure,” he says.

Leading medical organizations discourage their members from participating in executions, so the act often falls to corrections staffers. The extent of their training varies by state, but experts say it is rarely enough to make them as skilled as physicians. Other problems can arise simply because prison systems don’t put that many people to death.

“They’re only doing it a few times a year,” says Deborah Denno, a professor at Fordham University Law School and an expert in lethal injection. “They’re not executing enough people to get good at it.”

Dr. Jonathan Groner, a professor of surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, says the problems with Lockett’s execution may have come from prison officials trying to give the inmate too much too fast, causing a vein to rupture. Dr. David Waisel, who often testifies on behalf of inmates suing states over lethal injection protocols, says it’s possible that the drugs were absorbed not through Lockett’s veins but through the soft tissues surrounding it, which could cause severe pain over a prolonged period of time.

Meanwhile, Warner, the inmate who was scheduled to die after Lockett, awaits news of his fate. Fallin said that if the investigation surrounding Lockett’s execution isn’t complete by May 13, she would issue an additional stay of execution.

Attorneys involved in Lockett’s case hope the review will shed some light on what happened, but they’re skeptical that the state will perform the kind of thorough investigation they believe is required.

“That 25 minutes, that’s what I’m thinking about,” says Sanderford. “They kept the drugs secret all this time. Now they kept those 25 minutes secret. And God knows what went on then.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com