When Philip Pullman was 10 years old, he witnessed a vision that has stayed with him ever since. The year was 1956, and he was living in South Australia, where his stepfather was a pilot with Britain’s Royal Air Force. The River Murray floods that year had left huge parts of the region underwater, and he remembers being driven out to see it. “It was astonishing,” the 70-year-old British author says now. “It was an immense mass, as wide as the sea, of gray water whipped up by a cold wind. The power of it. It was an impression that never left me.”

It’s this memory that inspired the flood at the center of La Belle Sauvage, the first volume of the Book of Dust, Pullman’s new trilogy set in the universe of his fantasy series His Dark Materials. Released between 1995 and 2000, the three novels that launched the franchise entered the canon of young-adult fiction and, alongside the Harry Potter series, stands as an early example of the cross-generational appeal of the genre. In 2003, Pullman’s fellow Brits voted the entire trilogy their third favorite book of all time, after The Lord of the Rings and Pride and Prejudice.

His Dark Materials is mostly set in a parallel universe where the supernatural is everyday; ageless witches exist alongside warrior polar bears; and every human has a “daemon,” a kind of spirit animal with which it shares a soul. The books also wrestle with weighty metaphysical themes, influenced by the poetry of William Blake and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. The villains are the forces of organized religion, and the heroes seek to challenge and overturn the order of the monotheistic universe. The final book ends with Pullman’s heroine, Lyra, unwittingly restaging the fall of man and setting out to create a “Republic of Heaven,” a principled democracy rather than a dictatorship under the authority of God.

These heretical themes saw the books condemned by church groups in the U.S., especially after the 2007 movie adaptation of the first volume, The Golden Compass, brought them wider attention. In the following two years the trilogy was among the country’s most frequently challenged books, according to the American Library Association, as anxious parents attempted to have it removed from public and school libraries. “Atheism for kids,” the Catholic League announced in 2007, “that is what Philip Pullman sells.”

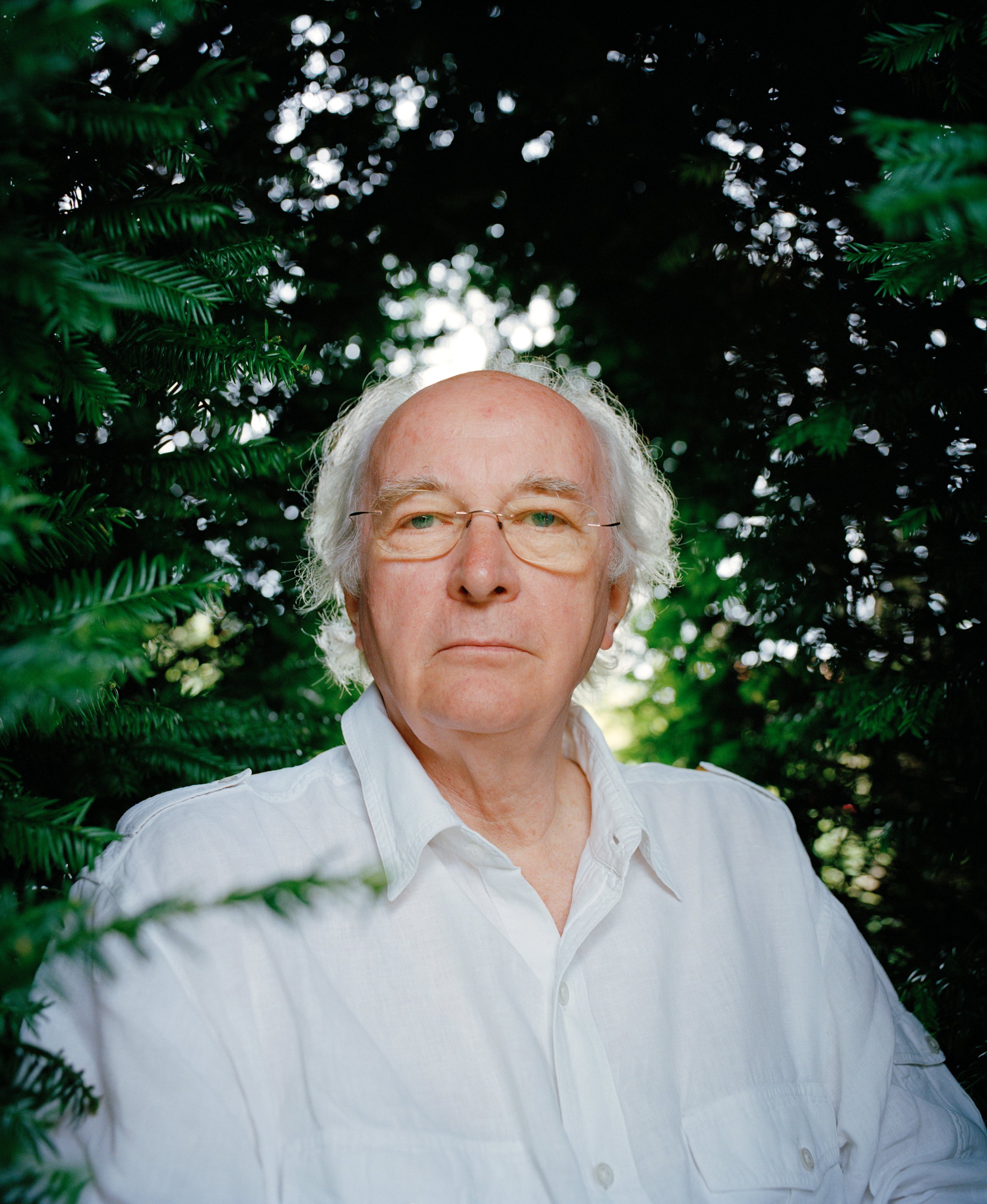

In person, Pullman doesn’t seem much like a threat to the moral order. He strikes an avuncular, professorial figure at home in his low-ceilinged cottage just outside of Oxford. But there’s a streak of eccentricity too. While he was writing La Belle Sauvage, he vowed not to cut his hair until he was finished. “It was superstition,” he says, “or a bargain with the muse or something. ‘If I don’t cut my hair, this book will be all right.’” He still has the hair, he says, stashed away in a Ziploc bag. “I’m going to give it to the Bodleian Library,” he adds, referring to the University of Oxford’s research library.

The fury over His Dark Materials has worn away over the years, and the letters Pullman once regularly received from readers telling him he was going to hell seldom come anymore. He sounds rather disappointed to report that “clearly, no evident evil has sprouted from its presence in the world for 20 years. There’s nothing they can point to and say, This man ought to be burned at the stake.”

Despite the presence of a biblical-style flood in its second half, there’s little to object to in La Belle Sauvage, which comes out on Oct. 19. Where the first trilogy traverses worlds to question the fundamentals of existence, this prequel shrinks the canvas to tell a more simplistic story about “the dangers of what Blake called single vision,” Pullman explains, “a narrow, dogmatic point of view that excludes every other angle of vision but what it deems to be true.”

Set about a decade before the events of the original trilogy, La Belle Sauvage tells the story of Malcolm, the 11-year-old son of an innkeeper in Oxford. In between helping out at his dad’s pub and riding the city’s canals in the beloved canoe that gives the book its title, Malcolm is introduced to a baby, Lyra, who is being looked after by an order of nuns at a nearby priory. Over the course of the novel, set almost entirely in Oxfordshire, it falls to Malcolm to protect Lyra from the forces threatening her—not just the rising floodwaters but also the various agents of a tyrannical church, or “Magisterium,” now growing in power.

In the book’s first half Pullman delves into the authority the Magisterium has accumulated over this alternative version of Britain. It’s a grim vision of totalitarianism: dissenters are “disappeared” or forced to go into hiding. Scientists must carry out their work in secret. A sinister youth organization turns schoolkids into informers. The historical parallels with the Spanish Inquisition and the Soviet Union are unmistakable, but Pullman says similar forces still exist today. “In the Middle East, and in isolated pockets of Western Europe, we see people, especially young men, who love the idea of an absolute answer to everything,” he says. “That cast of mind has not very often acquired political power, but when it does it’s absolutely murderous.”

Eventually the flood comes, transporting Malcolm into more fantastical territory as he, Lyra and teenage companion Alice travel through a mysterious, shadowy world inspired by British folklore. As an influence, Pullman cites The Secret Commonwealth, a treatise written by Scottish clergyman Robert Kirk in the early 1690s on the world of fairies, witchcraft and second sight. “I’m fascinated by that world,” he says. “And it’s the complete opposite of the world that science tells us about.”

Although Pullman is an admirer of writers about science, he believes they are as susceptible to the dangers of a “single vision” as politicians or zealots. “They might say X is nothing more than Y,” he says, “or love is nothing more than the excitation of neurons in the brain, for example. I would much rather say love is the excitation of neurons in the brain, among other things. And we’re not truly seeing it unless we see all of those things. And that is something Lyra and Malcolm will have to learn.”

Lyra plays little more than a passive role in this book, being only a few months old. But the next book—titled The Secret Commonwealth—will visit her 20 years later. “She’s going to be an undergraduate and her own woman, and she’s going to have the beginnings of an adult’s preoccupations,” Pullman says. “And, um, there will be trouble.” He hints that it will be partly set in Central Asia and that there will be a “bit of a surprise” in store about Lyra’s connection to a major character in La Belle Sauvage.

There’s more of Pullman’s work on the horizon. The BBC is developing a television adaptation of the first trilogy penned by Jack Thorne, the playwright responsible for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. The Golden Compass was an infamous box-office flop, and while Pullman won’t be drawn out about that, he does say he feels his work is better suited to the small screen. “The thing about a movie is that you’ve got to distill 12 to 13 hours of story into 120 minutes, and, of course, you can’t do it because you have to leave things out,” he says. “The great advantage of the new world of long-form television is that you can allow the time for a story to develop.”

The new world of television has also given us Game of Thrones, another epic series of books set in a parallel fantasy universe and made into a very successful HBO show. Is he a fan? “Not really my sort of thing,” Pullman says. “I don’t watch or read very much fantasy.” He considers himself a realist more than a fabulist, a fact that might surprise ardent Pullmaniacs obsessed with the universe he has built.

In fact, he says, the driving force behind his choice of genre is less a desire to build new worlds than a simple reluctance to explore this one. “It’s because I’m a lazy bastard,” he jokes. “Too idle to get up off my backside and do any research in the real world.” Pullman is similarly humble when I ask what he wants the reader to take away from this new book, what that great flood inspired by a childhood vision really means. “The meaning of the book is never just what the author thinks it is. It’s a great mistake to rely on the author to tell you,” he says. “We don’t know. The meaning is only what emerges when the book and the reader meet.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com