The National Constitution Center is awarding its 2016 Liberty Medal to Rep. John Lewis (D-Georgia) on Monday “for his courageous dedication to civil rights and the Constitution,” citing the 1965 march he and Hosea Williams led across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on March 7, 1965.

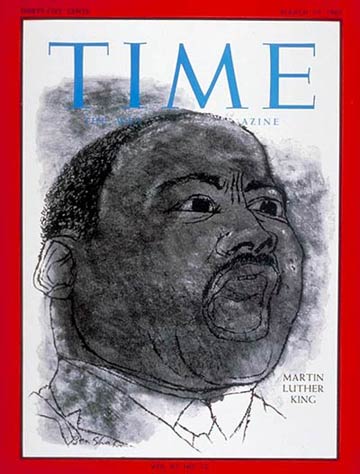

At the time, Selma represented the deep problem of inequality in voting: in a city that was almost exactly half white and half African-American, 99% of those registered to vote were white, reported TIME’s March 19, 1965, cover story about the protest. As the call to register more black voters became ever louder—and opposition became more violent—Martin Luther King, Jr. called for a voting-rights demonstration in the form of a march from Selma to the state capital at Montgomery. But, as the magazine reported, his plan to lead it had to be changed at the last minute because his personal safety was at risk.

Enter Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Despite the state Governor George Wallace’s order not to march, he started at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church with a group that TIME estimated back then to be 650 African-Americans and a few whites. “I don’t understand how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam but not to Alabama,” he later recalled saying at the time.

Walking two by two, the group got as far as the Edmund Pettus Bridge before a line of state troopers shut it down. As TIME described the scene:

Suddenly the clubs started swinging. From the sidelines, white townspeople raised their voices in cheers and whoops. Joined now by the possemen and deputies, the patrolmen waded into the screaming mob…Now came the sound of canisters being fired…Within seconds the highway was swirling with white and yellow clouds of smoke, raging with the cries of men…The mounted men uncoiled bull whips and lashed out viciously as the horses’ hoofs trampled the fallen.

That day became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Lewis was one of the dozens hospitalized, knocked unconscious by a trooper’s nightstick. “I thought I saw death,” he’d later say. Demonstrations took place in cities nationwide and Martin Luther King, Jr. declared a “symbolic” March 9 march as far as the bridge. Meanwhile, concerned Americans—especially members of the clergy—flocked to Selma.

“In Indianapolis, Jewish Mission Worker David Goldstein had an appointment to seek a salary raise from his boss; he canceled it and headed for Selma,” TIME’s cover story reported. “University of Chicago Divinity School Instructor Jay Wilcoxen arrived home to find that his wife had taken it upon herself to get him a plane reservation.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in federal troops, and on March 15, sent a voting rights bill to Congress. He used the words “We shall overcome,” echoing a mantra of the movement in what Lewis considers “one of the most meaningful and powerful speeches any modern president has made on voting rights.”

A third march from Selma to Montgomery was successfully completed on March 25.

On the event’s 30th anniversary, TIME would describe Bloody Sunday and the Selma marches as “a turning point in the civil rights movement” that led to not only President Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act into law on Aug. 6, 1965, but also to the elimination of discriminatory literacy tests and poll taxes.

Lewis made headlines this summer for relating the persistence of the civil rights marchers in Selma to Democrats’ persistence on another cause, when he led a June sit-in on the House floor for more than 25 hours to pressure the Republican majority to act on gun-control legislation.

“More than 50 years ago, I crossed the bridge not just one time, but it took us three times to make it all the way from Selma to Montgomery,” he said. “We have other bridges to cross.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com