The new Martin Luther King Jr. biopic Selma “differs from the rushed cradle-to-grave biopics that audiences have come to expect at this time of year,” TIME’s Daniel D’Addario wrote in his review of the movie, because “it goes deep, patiently relating the events of just a few weeks.”

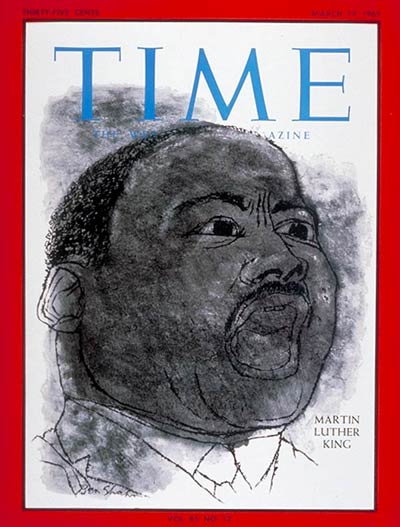

Those weeks took place in early 1965, and it was clear to anyone watching then that the events would have an influence far beyond that year. In fact, TIME chose to put King on the cover of the magazine that March, as events in Selma came to a head.

“Last week the Negro’s struggle to achieve that right exploded into an orgy of police brutality, of clubs and whips and tear gas, of murder, of protests and parades and sit-ins in scores of U.S. cities and in the White House itself,” the cover story began. “It was a week in which the potential for further violence was so great that President Johnson signed an order that would have dispatched federal troops to Alabama on a moment’s notice. It was a week of intense pressures and back-room dealings, of quick emotionalism and easily achieved righteousness. And it was a very trying week for the foremost leader of the civil rights movement, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.”

Selma, the article continued, was a 99%-white city, proud of its old-fashioned values. It had already been the site of several federal voting-rights suits, but Sheriff James Clark continued to thwart black citizens’ efforts to register to vote. For weeks, King had been leading potential voters to try anyway. But after a young man named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot, marching to register was no longer enough: On March 7, 1965, King and his followers tried to march all the way to the state capitol in Montgomery. At the Edmund Pettus Bridge, TIME reported, “troopers stood three-deep across all four lanes of the highway.” The report continued:

Suddenly the clubs started swinging. From the sidelines, white townspeople raised their voices in cheers and whoops. Joined now by the possemen and deputies, the patrolmen waded into the screaming mob. The marchers retreated for 75 yards, stopped to catch their breath. Still the troopers advanced. Now came the sound of canisters being fired. A Negro screamed: “Tear gas!” Within seconds the highway was swirling with white and yellow clouds of smoke, raging with the cries of men. Choking, bleeding, the Negroes fled in all directions while the whites pursued them. The mounted men uncoiled bull whips and lashed out viciously as the horses’ hoofs trampled the fallen. “O.K., [n—-r]!” snarled a posseman, flailing away at a running Negro woman. “You wanted to march —now march!”

Dozens of marchers ended up injured. But the world was watching. Protests began in cities around the nation. The President spoke up against the police brutality. Another march from Selma was planned.

That one was stopped as well, and after that TIME’s issue must have then gone to press. It wasn’t until the April 2 issue that a full report on the eventual success of the marchers—who finally made it to Montgomery by the end of the month— appeared in TIME. Though the Civil Rights movement still had a long way to go, the magazine’s description of that march is worthy of any Hollywood ending: “In the procession, whites and Negroes, clergymen and beatniks, old and young, walked side by side.”

Browse the Mar. 19, 1965, issue here, in the TIME Vault: Martin Luther King

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com