It’s been almost a decade since the debut of the Netflix Prize, a $1 million bounty for the person or group that could best improve the company’s movie suggestion algorithm. Netflix’s much-touted recommendation engine was, at the time, one of the driving forces of its success as a DVD-by-mail service. The idea that a computer could churn through thousands of movie cast, plots and genre and pluck out the one or two that a particular viewer might enjoy was novel and exciting. The highly publicized prize proved to be great marketing for the company.

Fast forward nine years and the phrase on the tip of Netflix executives’ tongues isn’t “smart algorithms”—it’s “original programming.” Sure, Netflix still uses software to recommend titles available on its streaming platform, but the company says what’s really driving new subscriptions are the dozen or so originals it has bankrolled over the last two years, including flagship series like House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black. As The New Yorker’s Tim Wu points out, today Netflix’s most valuable “algorithm” might be chief content officer Ted Sarandos, who’s in charge of picking which programs the company funds.

This is just one example of human expertise and insight complementing automated, data-driven experiences in Silicon Valley. But it represents a broader sea-change in thinking about what humans can do computers simply can’t.

Since the very first Google query in 1998, Internet denizens have been taught that ever-more-intelligent algorithms would one day be able to serve them recommendations that, if not altogether perfect, were at least much better than anything a lowly human could ever muster. Each of us was supposed to have our own personalized, pristine digital experience calculated with such exaction by computers that you’d feel uncomfortable even questioning the algorithm’s authority.

MORE: 5 Reasons to Buy a PlayStation 4 Right Now

But tech companies seem to be jutting up against the limits of what an algorithm can achieve, at least affordably. (The algorithm that won the Netflix prize was never actually implemented because it was prohibitively expensive). Now, the coders are having to make more room for the curators and the creatives across a variety of sectors.

Last month, Apple launched Apple Music, an on-demand streaming service similar to Spotify. Human curators are a core selling point. Music experts hand-select songs for oddly specific but weirdly compelling playlists to serve to users based on their favorite artists and genres. Meanwhile an Internet radio station called Beats 1 has become the centerpiece of the service, featuring live DJs, interviews with artists and songs far afield of the Billboard charts. The old-school format’s launch was followed as closely by the tech press as the inaugural fireside chat.

Even in areas where it seemed as though algorithms had decidedly won out, human input is gaining greater importance. Facebook’s News Feed is controlled by a closely guarded algorithm that sorts through the thousands of posts available to a given user each day and shows only the ones that it thinks will be most interesting to each individual person. For the last year, though, the company has been paying hundreds of people around the country to grade the News Feed’s quality and offer suggestions for improvements. Insight from these everyday users has led to algorithm improvements that a computer program seeking to boost engagement metrics could never discern, such as the need to show sad or serious posts prominently even though they may not garner a lot of “Likes.”

MORE: YouTube Is About to Look Very Different

The approach seems to be paying off. Facebook’s number of users and the average time spent on-site has continued to climb as it has made its algorithm more human. The human elements of Apple Music, such as Beats 1, have received high praise even as people have griped about the service’s confusing interface and rocky stability. Even newcomer Snapchat has gotten in on curation. It’s hard to imagine an algorithm replicating the mini-narratives that emerge in Snapchat’s “Live Stories,” the 24-hour local pastiches the burgeoning social network curates from snaps from its 100 million users. These stories now attract 20 million viewers a day, and the format has been so successful that Twitter is planning to imitate it this fall with Project Lightning, an upcoming feature that will show a human-curated feed of interesting tweets, photos and videos tied to major events.

Algorithms are here to stay, of course. They have the ability to analyze millions of pieces of data faster than a team of humans ever could. The emergence of Big Data—the vast trove of data generated by people and devices—is only likely to make them more crucial. But in the future, recommendation systems that meld human and algorithmic input may be more commonplace. Apple Music analyzes a user’s past listening activity to decide which human-curated playlists to present, for instance. Netflix uses its massive trove of data about people’s viewing habits to determine what types of shows to bankroll (though, Sarandos and other executives give the final green light).

We increasingly rely on computers to guide us in the right direction, but we may still need a living, breathing human to be that final arbiter of taste.

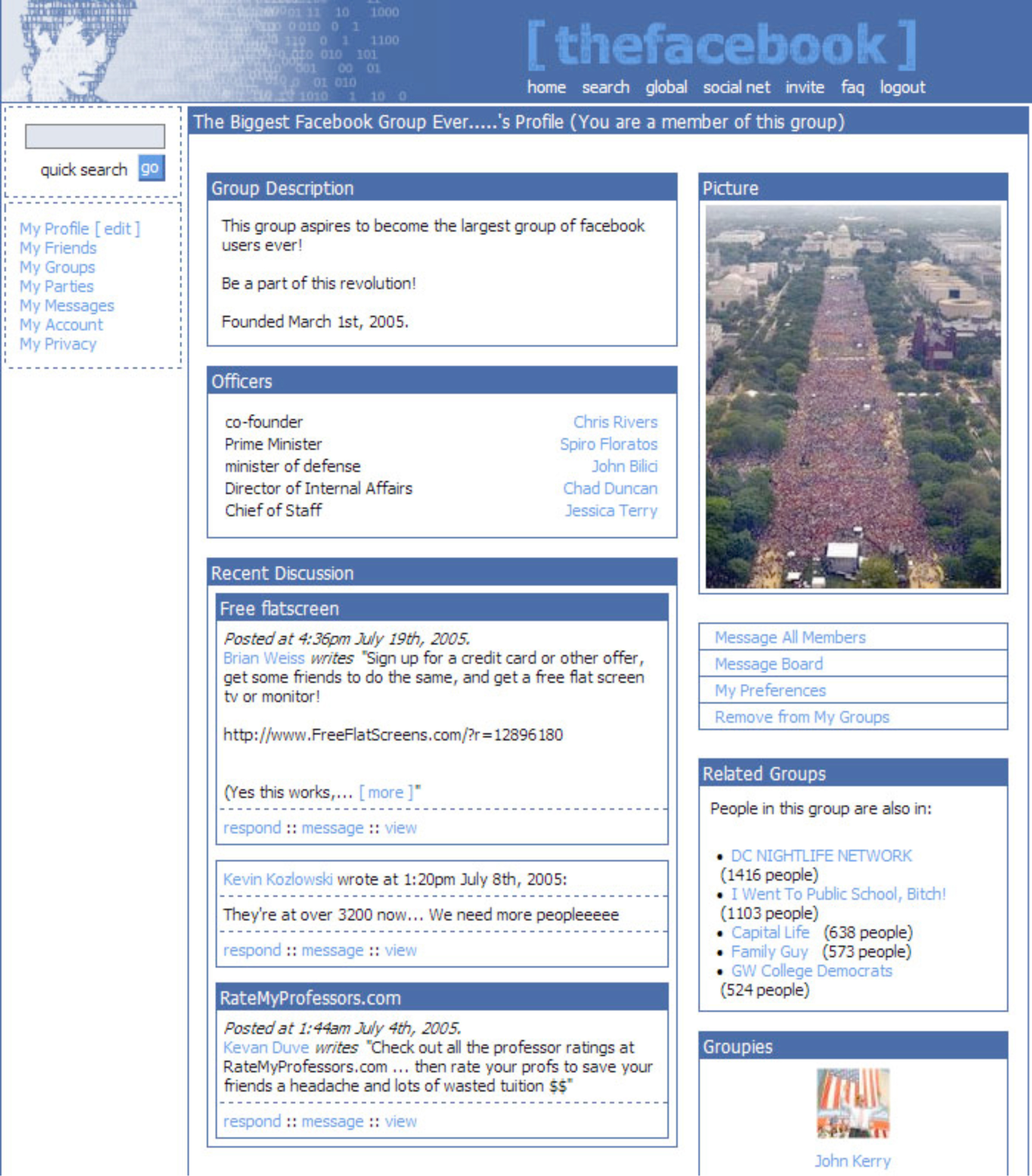

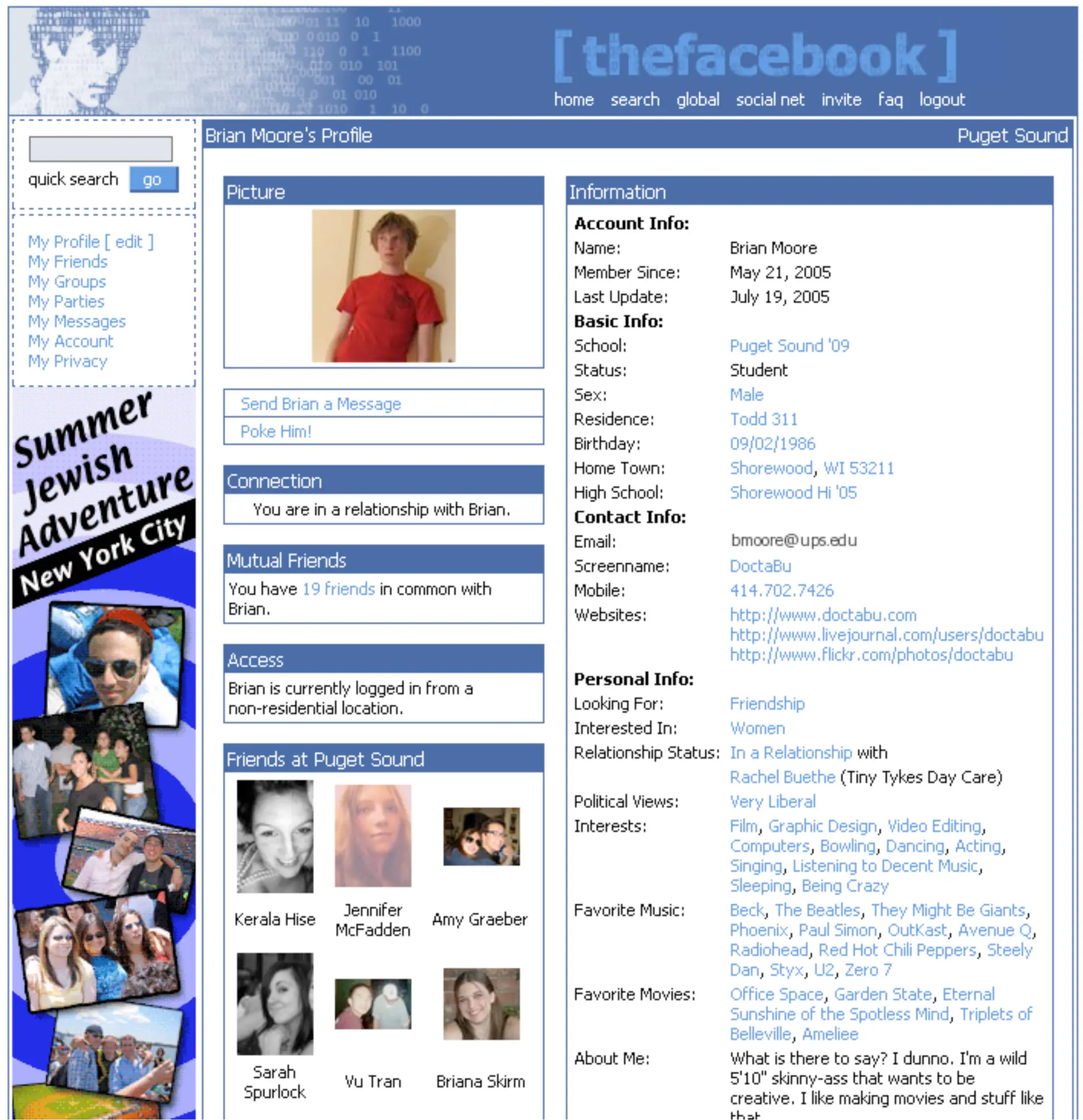

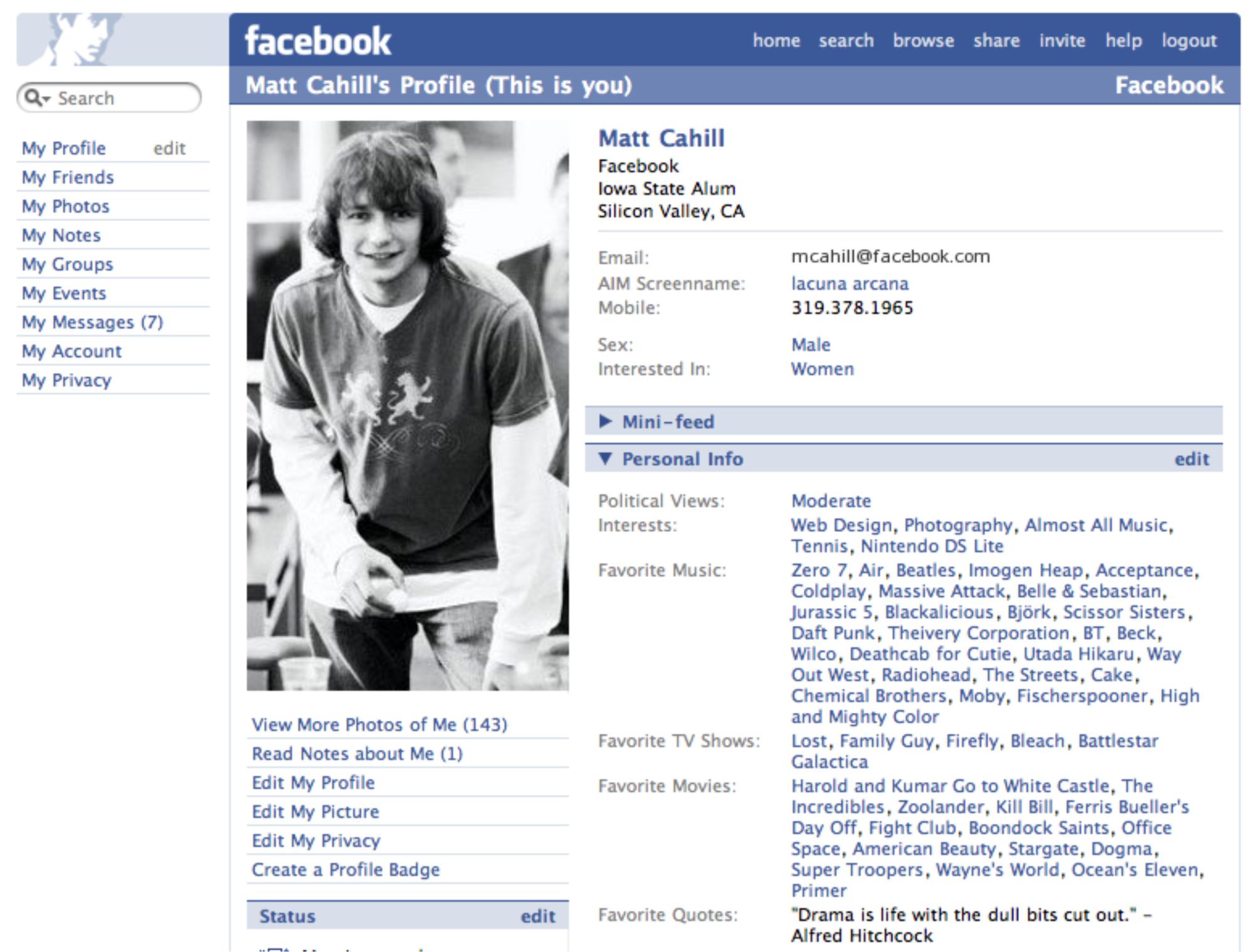

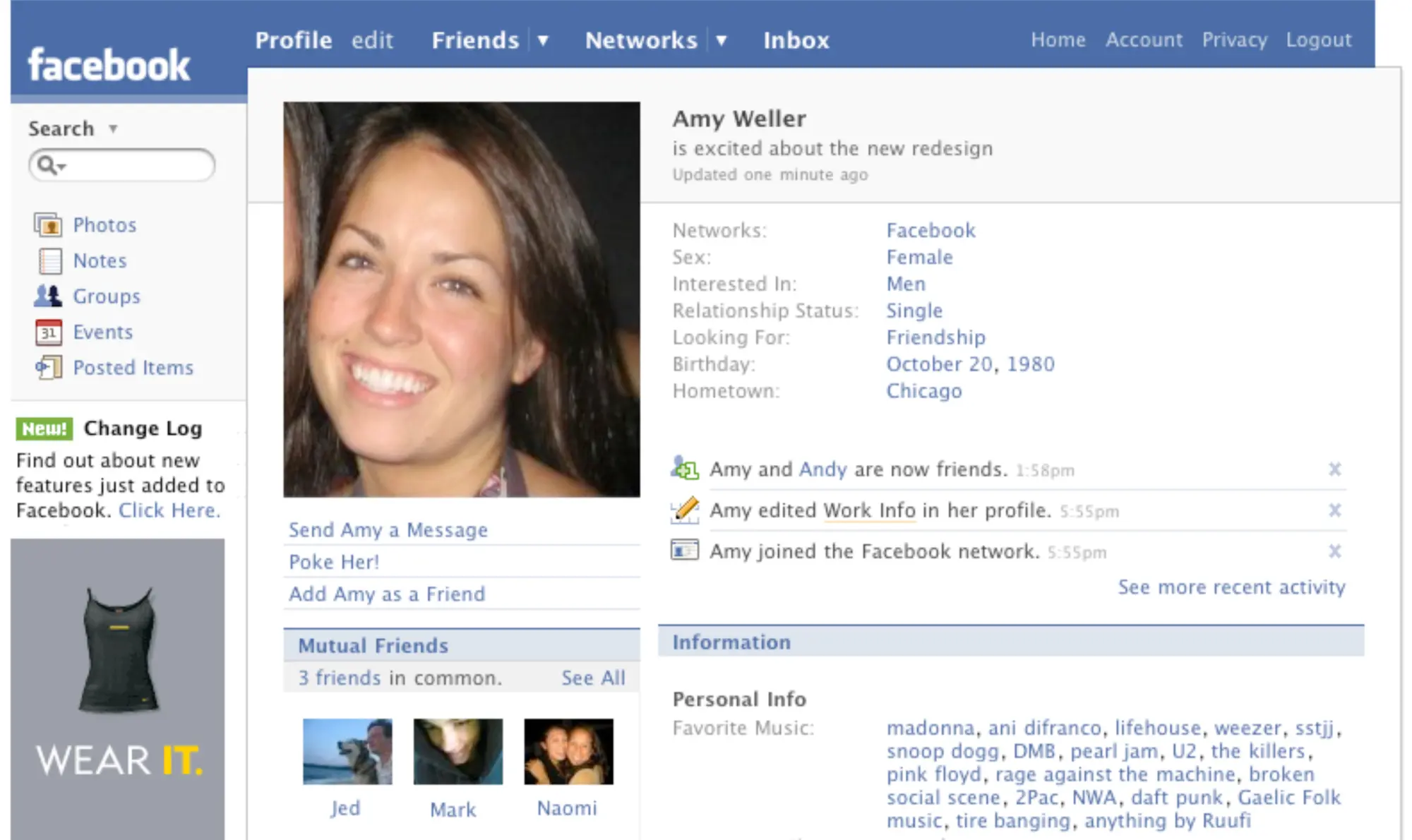

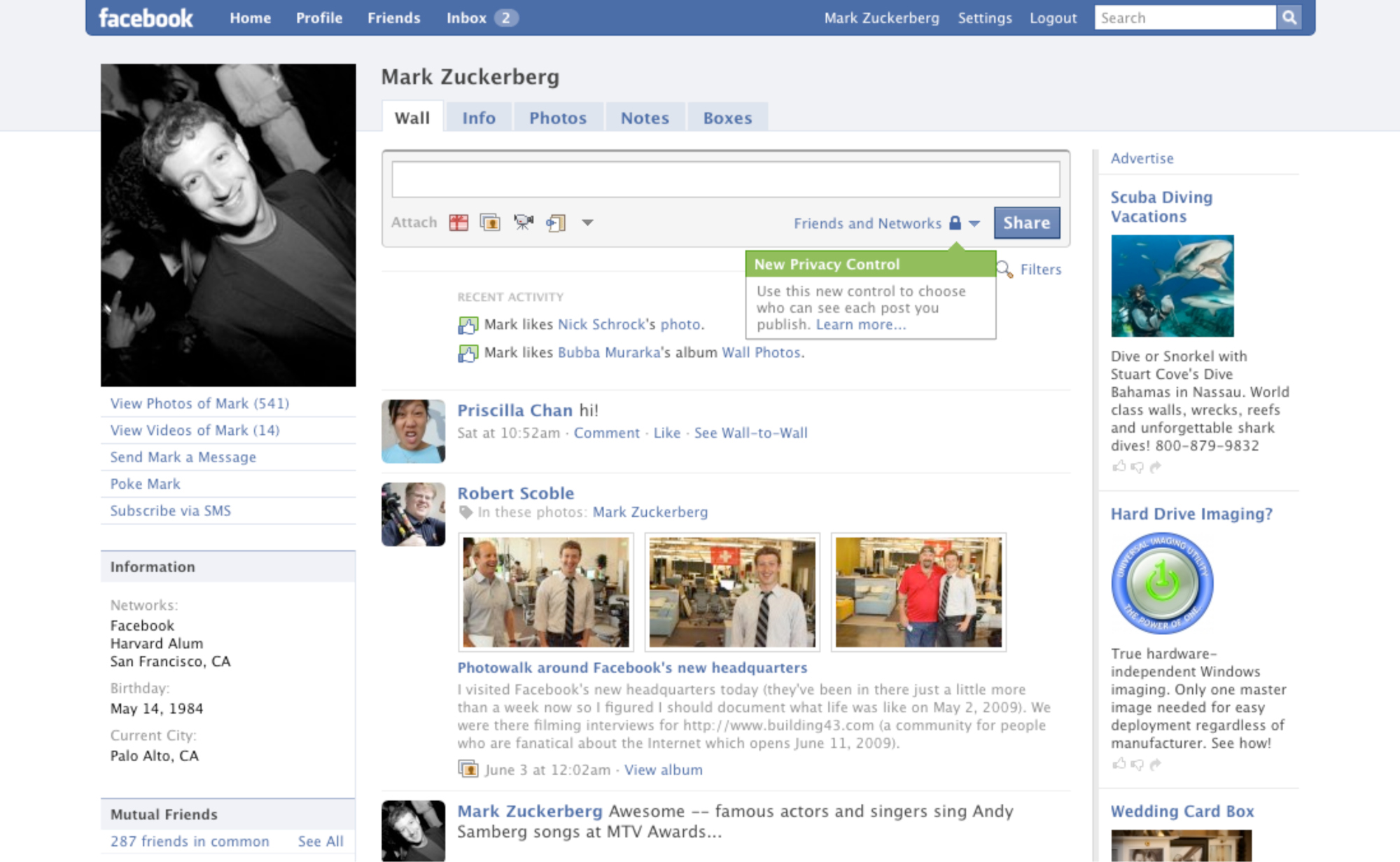

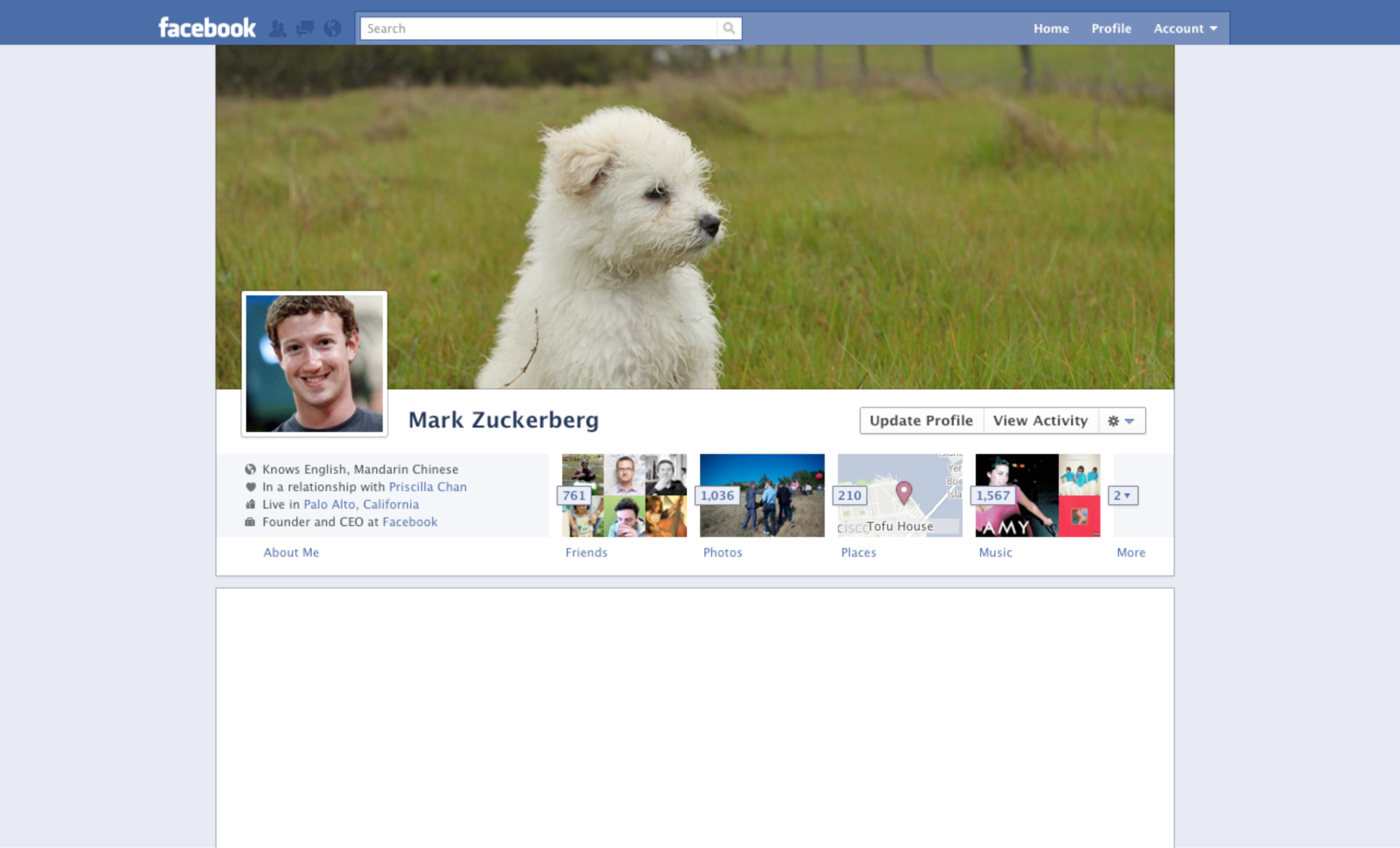

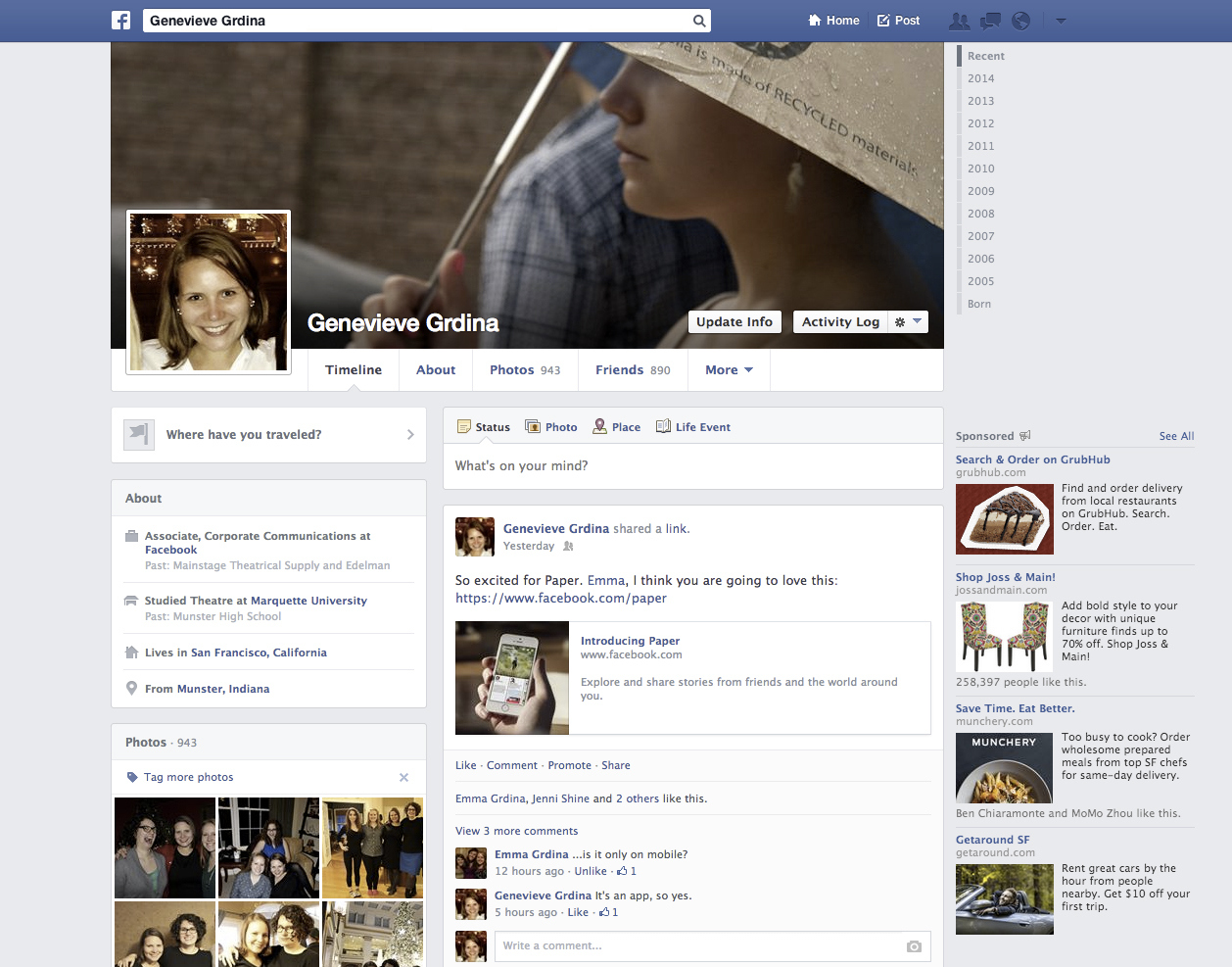

This Is What Your Facebook Profile Looked Like Over the Last 11 Years

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com