If you’re an average reader, I’ve got your attention for 15 seconds, so here goes: We are getting a lot wrong about the web these days. We confuse what people have clicked on for what they’ve read. We mistake sharing for reading. We race towards new trends like native advertising without fixing what was wrong with the old ones and make the same mistakes all over again.

Not an average reader? Maybe you’ll give me more than 15 seconds then. As the CEO of Chartbeat, my job is to work with the people who create content online (like Time.com) and provide them with real-time data to better understand their readers. I’ve come to think that many people have got how things work online quite mixed up.

Here’s where we started to go wrong: In 1994, a former direct mail marketer called Ken McCarthy came up with the clickthrough as the measure of ad performance on the web. From that moment on, the click became the defining action of advertising on the web. The click’s natural dominance built huge companies like Google and promised a whole new world for advertising where ads could be directly tied to consumer action.

However, the click had some unfortunate side effects. It flooded the web with spam, linkbait, painful design and tricks that treated users like lab rats. Where TV asked for your undivided attention, the web didn’t care as long as you went click, click, click.

In 20 years, everything else about the web has been transformed, but the click remains unchanged, we live on the click web. But something is happening to the click web. Spurred by new technology and plummeting click-through rates, what happens between the clicks is becoming increasingly important and the media world is scrambling to adapt. Sites like the New York Times are redesigning themselves in ways that place less emphasis on the all-powerful click. New upstarts like Medium and Upworthy are eschewing pageviews and clicks in favor of developing their own attention-focused metrics. Native advertising, advertising designed to hold your attention rather than simply gain an impression, is growing at an incredible pace.

It’s no longer just your clicks they want, it’s your time and attention. Welcome to the Attention Web.

At the core of the Attention Web are powerful new methods of capturing data that can give media sites and advertisers a second-by-second, pixel-by-pixel view of user behavior. If the click is the turnstile outside a stadium, these new methods are the TV control room with access to a thousand different angles. The data these methods capture provide a new window into behavior on the web and suggests that much of the facts we’ve taken for granted just ain’t true.

Myth 1: We read what we’ve clicked on

For 20 years, publishers have been chasing pageviews, the metric that counts the number of times people load a web page. The more pageviews a site gets, the more people are reading, the more successful the site. Or so we thought. Chartbeat looked at deep user behavior across 2 billion visits across the web over the course of a month and found that most people who click don’t read. In fact, a stunning 55% spent fewer than 15 seconds actively on a page. The stats get a little better if you filter purely for article pages, but even then one in every three visitors spend less than 15 seconds reading articles they land on. The media world is currently in a frenzy about click fraud, they should be even more worried about the large percentage of the audience who aren’t reading what they think they’re reading.

The data gets even more interesting when you dig in a little. Editors pride themselves on knowing exactly what topics can consistently get someone to click through and read an article. They are the evergreen pageview boosters that editors can pull out at the end of the quarter to make their traffic goals. But by assuming all traffic is created equal, editors are missing an opportunity to build a real audience for their content.

Our data team looked at topics across a random sample of 2 billion pageviews generated by 580,000 articles on 2000 sites. We pulled out the most clicked-on topics and then contrasted topics that received a very high level of attention per pageview with those that received very little attention per pageview. Articles that were clicked on and engaged with tended to be actual news. In August, the best performers were Obamacare, Edward Snowden, Syria and George Zimmerman, while in January the debates around Woody Allen and Richard Sherman dominated.

The most clicked on but least deeply engaged-with articles had topics that were more generic. In August, the worst performers included Top, Best, Biggest, Fictional etc while in January the worst performers included Hairstyles, Positions, Nude and, for some reason, Virginia. That’s data for you.

All the topics above got roughly the same amount of traffic, but the best performers captured approximately 5 times the attention of the worst performers. Editors might say that as long as those topics are generating clicks, they are doing their job, but that’s if the only value we see in content is the traffic, any traffic, that lands on that page. Editors who think like that are missing the long game. Research across the Chartbeat network has shown that if you can hold a visitor’s attention for just three minutes they are twice as likely to return than if you only hold them for one minute.

The most valuable audience is the one that comes back. Those linkbait writers are having to start from scratch every day trying to find new ways to trick clicks from hicks with the ‘Top Richest Fictional Public Companies’. Those writers living in the Attention Web are creating real stories and building an audience that comes back.

Myth 2: The more we share the more we read

As pageviews have begun to fail, brands and publishers have embraced social shares such as Facebook likes or Twitter retweets as a new currency. Social sharing is public and suggests that someone has not only read the content but is actively recommending it to other people. There’s a whole industry dedicated to promoting the social share as the sine qua non of analytics.

Caring about social sharing makes sense. You’re likely to get more traffic if you share something socially than if you did nothing at all: the more Facebook “likes” a story gets, the more people it reaches within Facebook and the greater the overall traffic. The same is true of Twitter, though Twitter drives less traffic to most sites.

But the people who share content are a small fraction of the people who visit that content. Among articles we tracked with social activity, there were only one tweet and eight Facebook likes for every 100 visitors. The temptation to infer behaviour from those few people sharing can often lead media sites to jump to conclusions that the data does not support.

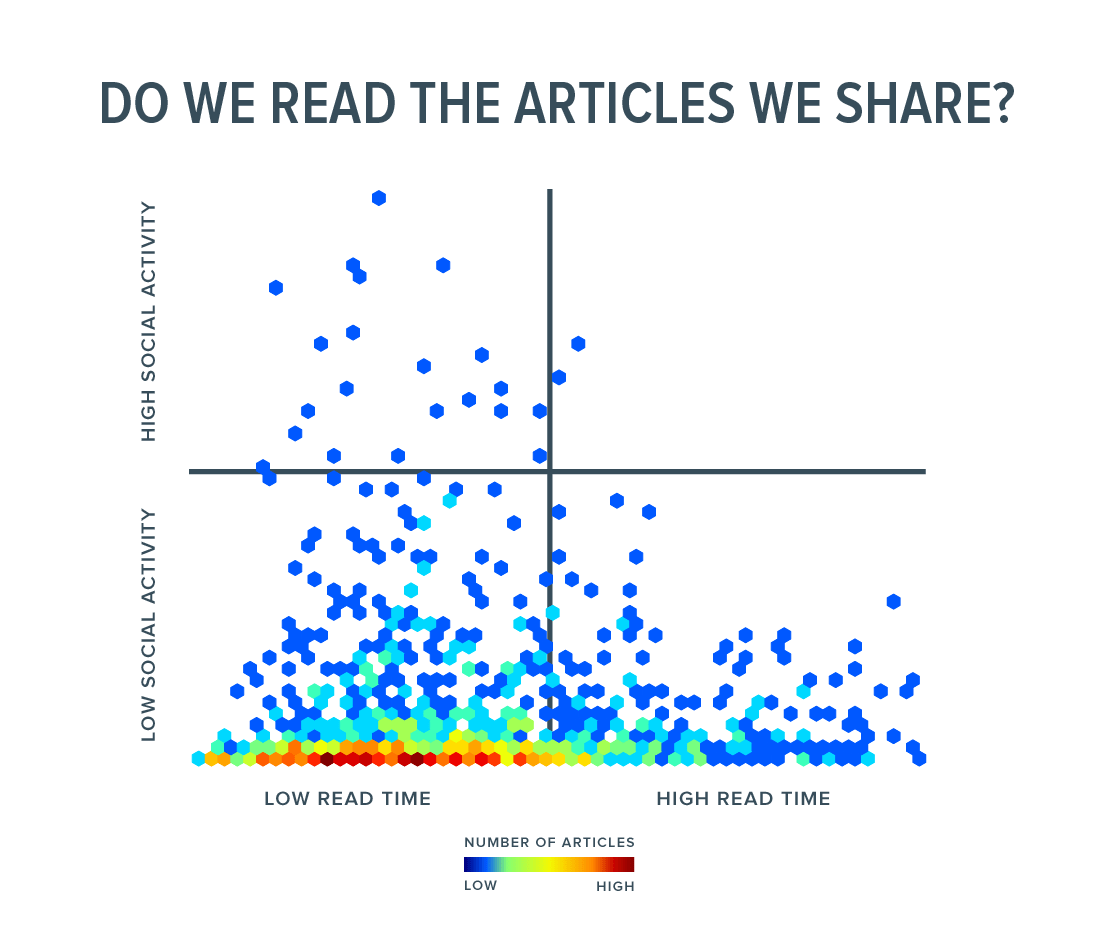

A widespread assumption is that the more content is liked or shared, the more engaging it must be, the more willing people are to devote their attention to it. However, the data doesn’t back that up. We looked at 10,000 socially-shared articles and found that there is no relationship whatsoever between the amount a piece of content is shared and the amount of attention an average reader will give that content.

When we combined attention and traffic to find the story that had the largest volume of total engaged time, we found that it had fewer than 100 likes and fewer than 50 tweets. Conversely, the story with the largest number of tweets got about 20% of the total engaged time that the most engaging story received.

Bottom line, measuring social sharing is great for understanding social sharing, but if you’re using that to understand which content is capturing more of someone’s attention, you’re going beyond the data. Social is not the silver bullet of the Attention Web.

Myth 3: Native advertising is the savior of publishing

Media companies, desperate for new revenue streams are turning to native advertising in droves. Brands create or commission their own content and place it on a site like the New York Times or Forbes to access their audience and capture their attention. Brands want their message relayed to customers in a way that does not interrupt but adds to the experience.

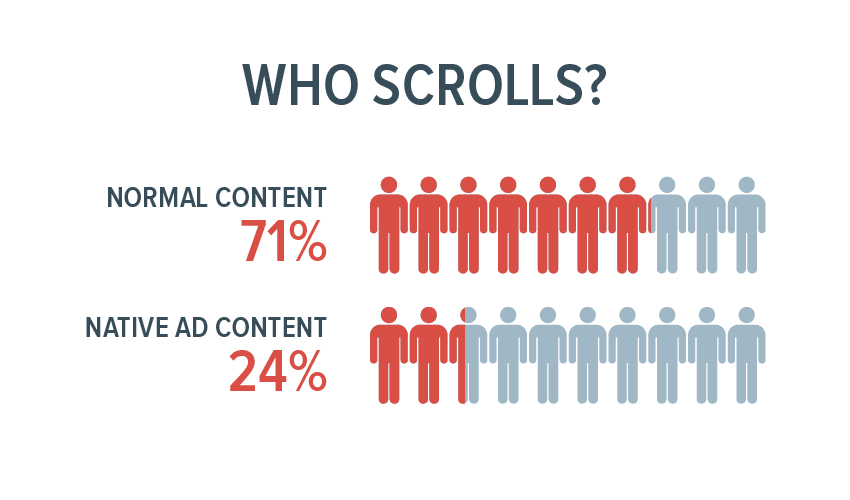

However, the truth is that while the emperor that is native advertising might not be naked, he’s almost certainly only wearing a thong. On a typical article two-thirds of people exhibit more than 15 seconds of engagement, on native ad content that plummets to around one-third. You see the same story when looking at page-scrolling behavior. On the native ad content we analyzed, only 24% of visitors scrolled down the page at all, compared with 71% for normal content. If they do stick around and scroll down the page, fewer than one-third of those people will read beyond the first one-third of the article.

What this suggests is that brands are paying for — and publishers are driving traffic to — content that does not capture the attention of its visitors or achieve the goals of its creators. Simply put, native advertising has an attention deficit disorder. The story isn’t all bad. Some sites like Gizmodo and Refinery29 optimize for attention and have worked hard to ensure that their native advertising experience is consistent with what visitors come to their site for. They have seen their native advertising perform as well as their normal content as a result.

The lesson here is not that we should give up on native advertising. Done right, it can be a powerful way to communicate with a larger audience than will ever visit a brand’s homepage. However, driving traffic to content that no one is reading is a waste of time and money. As more and more brands start to care about what happens after the click, there’s hope that native advertising can reach a level of quality that doesn’t require tricks or dissimulation; in fact, to survive it will have to.

Myth 4: Banner ads don’t work

For the last few years there have been weekly laments complaining that the banner ad is dead. Click-through rates are now averaging less than 0.1% and you’ll hear the words banner blindness thrown about with abandon. If you’re a direct response marketer trying to drive clicks back to your site then yes, the banner ad is giving you less of what you want with each passing year.

However, for brand advertisers rumors of the banner ad’s demise may be greatly exaggerated. It turns out that if your goals are the traditional brand advertising goals of communicating your message to your audience then yes, most banner ads are bad…. but…. some banner ads are great! The challenge of the click web is that we haven’t been able to tell them apart.

Research has consistently shown the importance of great ad creative in getting a visitor to see and remember a brand. What’s less well known is the scientific consensus based on studies by Microsoft [pdf], Google, Yahoo and Chartbeat that a second key factor is the amount of time a visitor spend actively looking at the page when the ad is in view. Someone looking at the page for 20 seconds while an ad is there is 20-30% more likely to recall that ad afterwards.

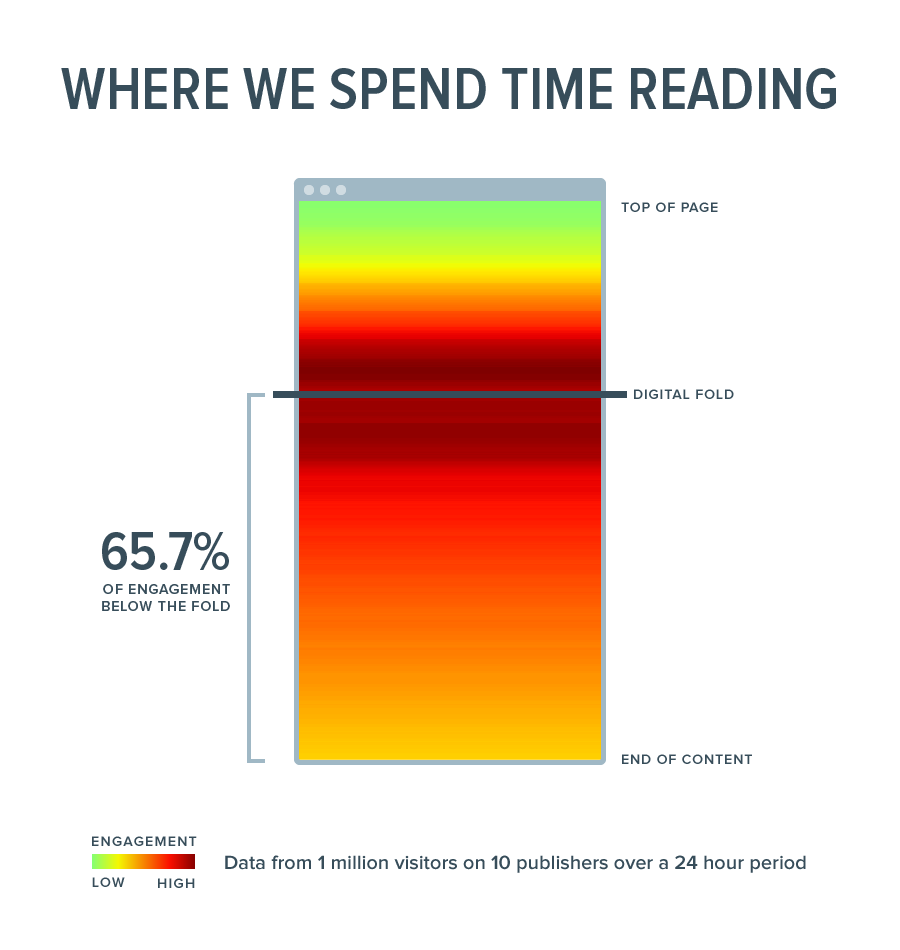

So, for banner ads to be effective the answer is simple. You have to create great creative and then get it in front of a person’s face for a long enough period for them to truly see it. The challenge for banner ads is that traditional advertising heuristics about what works have been placing ads on the parts of the page that capture the least attention, not the most.

Here’s the skinny, 66% of attention on a normal media page is spent below the fold. That leaderboard at the top of the page? People scroll right past that and spend their time where the content not the cruft is. Yet most agency media planners will still demand that their ads run in the places where people aren’t and will ignore the places where they are.

Savvy web natives like Say Media and Vox, as well as established players like the Financial Times, are driven by data more than tradition and are shaping their advertising strategy to optimize for experience and attention. A small cadre of innovative media planners are also launching an insurgency and taking advantage of their peers’ adhesion to old heuristics to benefit from asymmetrical information about what’s truly valuable.

For quality publishers, valuing ads not simply on clicks but on the time and attention they accrue might just be the lifeline they’ve been looking for. Time is a rare scarce resource on the web and we spend more of our time with good content than with bad. Valuing advertising on time and attention means that publishers of great content can charge more for their ads than those who create link bait. If the amount of money you can charge is directly correlated with the quality of content on the page, then media sites are financially incentivized to create better quality content. In the seeds of the Attention Web we might finally have found a sustainable business model for quality on the web.

This move to the Attention Web may sound like a collection of small signals and changes, but it has the potential to transform the web. It’s not just the publishers of quality content who win in the Attention Web, it’s all of us. When sites are built to capture attention, any friction, any bad design or eye-roll-inducing advertorials that might cause a visitor to spend a second less on the site is bad for business. That means better design and a better experience for everyone. A web where quality makes money and great design is rewarded? That’s something worth paying attention to.

Tony Haile is the CEO of Chartbeat, a data analytics company that counts Time.com and more than 4,000 top publishers and brands as its clients.

More: A Look At The Deep Web

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: All Those Presidential Pardons Give Mercy a Bad Name

Contact us at letters@time.com