From impeachment to Iran, the House Speaker is taking on President Trump

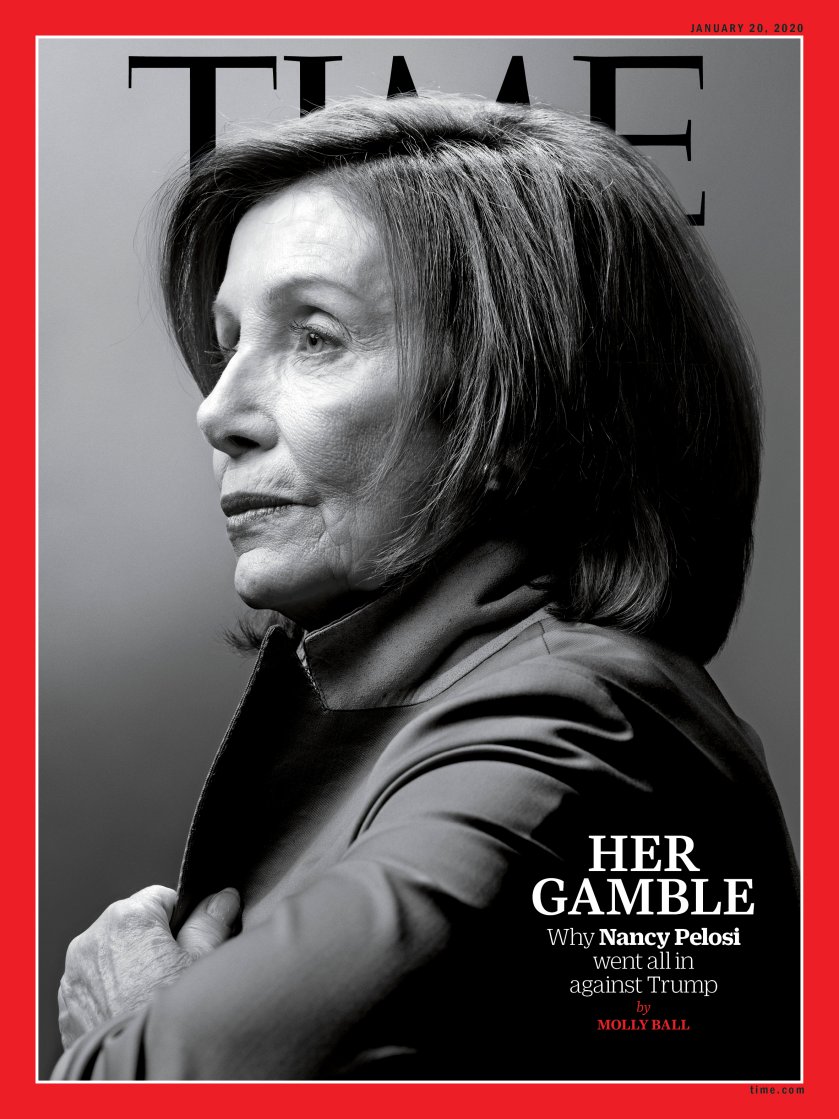

Nancy Pelosi isn’t wild about the question. The impeachment of President Donald Trump is under way, and I’ve asked the Speaker of the House if she thinks it’s the most important thing she’ll ever do. We’re sitting in her elegant office in the Capitol, on gold-upholstered armchairs around a low table topped with a vase of hydrangeas. Over her shoulder, the sweeping view of the National Mall is shrouded in wintry clouds. For a long moment, the Speaker goes silent as she seems to compile in her mind the list of accomplishments she’d rather claim as her legacy.

“Apart from declaring war, this is the most important thing that the Congress can do,” she finally says. “I’m most proud of the Affordable Care Act. But this is the most serious initiative that I’ve been involved in in my career.”

Pelosi has spent decades at the highest levels of politics, but the past 12 months have been arguably her most consequential. Returning to the speakership after eight years running the House Democratic minority, she established herself as counterweight and constrainer of this divisive President. She outmaneuvered Trump on policy, from the border wall he didn’t get to the budget agreement he signed loaded with goodies that Democrats wanted. She oversaw an unprecedented litigation effort against the Executive Branch, racking up landmark court victories. And she was the tactician behind the investigation that resulted in Trump’s impeachment on Dec. 18.

What is most striking about this moment in Pelosi’s career is that at the peak of power, she is not protecting her position but rather using it in aggressive, even risky ways. Impeaching Trump is a gamble for Pelosi. It has intensified Republicans’ fealty to the President, rallying his base and supercharging his campaign fundraising, potentially increasing his re-election chances. The polarizing effort could jeopardize Democrats who hold seats in Trump territory, and thereby endanger Pelosi’s House majority. With impeachment, Pelosi is betting her own place in history.

Pelosi has always been a risk-taker, from defying Chinese authorities by protesting at Tiananmen Square in 1991 to pushing Obamacare through the House with nary a vote to spare in 2010. But she is careful to cast impeachment not as a political gambit but as a project to preserve the checks and balances of American democracy. “That’s my responsibility: to protect the Constitution of the United States,” she says.

That battle is playing out on multiple fronts. As Congress returned and Trump launched the country into a potential conflict with Iran, Pelosi sought to rein him in. The House planned to vote Jan. 9 on a war powers resolution designed to limit the President’s ability to escalate the conflict. The behind-the-scenes court battle that Pelosi has field-marshaled aims not just to check Trump’s current power grabs, but also to set precedents that will stop future Presidents from doing the same, or worse.

And to Trump’s annoyance, Pelosi is declining to transmit the House’s two impeachment articles to the Senate. Instead of allowing Republican Senators to end the impeachment discussion with a quick vote, she is insisting that the upper chamber agree on rules for the trial first. “That doesn’t mean it has to meet my standards. When we see what [Mitch McConnell] has in mind, we will be prepared to send over” the articles, she tells TIME on Jan. 8, in her first public comments about the standoff. “We’ve upped the ante on this.”

Pelosi has told colleagues she’s had to wear a night guard because the White House makes her grind her teeth in her sleep. But her frustration is born of determination, not unease. In our interview, I asked her if the President’s nickname for her, Nervous Nancy, is accurate. “Pfft,” she says, waving a hand. “He’s nervous. Everything he says, he’s always projecting. He knows the case that can be made against him. That’s why he’s falling apart.”

But you’re not, I ask?

“No,” she says, her voice steady. “I’m emboldened.”

A year ago, it was hardly a given that Pelosi would emerge as the foil to the Trump presidency–or even that she would be Speaker at all. After Pelosi orchestrated Democrats’ 2018 midterm wins, an insurgent faction of the caucus moved to replace her with a younger, “less polarizing” figure. Pelosi squashed the uprising with characteristic discipline. Over the ensuing year, instead of holding grudges, she set to holding her diverse caucus together when ideology and identity threatened to splinter it.

For months, the Democrats’ biggest division was over impeachment. As colleagues and activists agitated for it, Pelosi spent most of the year resisting on the grounds that it could tear the country apart–and hurt her party. All the while, however, she was laying the groundwork behind the scenes to build a case if necessary. “It seemed like all of a sudden we were unified around an impeachment inquiry,” says Representative Katherine Clark of Massachusetts, the vice chair of the Democratic caucus. “But that was Nancy Pelosi using individual members and where they were to bring this to a–she always uses this word–a crescendo. So what appears to all of a sudden be a big moment is actually based on months of work.”

From start to finish, Pelosi has kept a tighter rein on the proceedings than the public realized, from major strategic decisions to minor stagecraft. It was Pelosi who decreed that the Intelligence Committee would take the lead in the inquiry, even though impeachment is generally considered to be the Judiciary Committee’s purview. (Past Judiciary hearings had devolved into a circus–particularly a Sept. 17 session in which the President’s former campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, openly mocked the proceedings.) It was Pelosi who decided that the Democrats’ hashtag for impeachment, #TruthExposed, seemed too harsh; they settled on #DefendOurDemocracy instead.

Pelosi refereed contentious disputes between chairmen with discretion. She signed off on every committee report and press release; aides say she caught typos in the Intelligence Committee’s final report before it went out. She decreed that the articles of impeachment would be limited to Trump’s actions in Ukraine rather than incorporating matters related to special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, as some of her members wanted. When Judiciary Committee lawyers debated whether to spend half a day of hearings on a presentation related to Mueller’s obstruction-of-justice probe, they appealed the question to the Speaker, noting that the staff was split. “Tell them I’m not split,” she replied, rejecting the idea. And while she allowed the committee’s final report to contain references to Mueller’s investigation, she demanded they be deleted from the accompanying announcement.

No aspect of the spectacle was too small to escape Pelosi’s control. When the Intelligence Committee held its public impeachment hearings in November, Pelosi noticed that chairman Adam Schiff’s head reached nearly to the top of his high-backed chair. After Intelligence finished its work, Judiciary, chaired by Representative Jerry Nadler, was slated to hold hearings in the same room. Pelosi thought if he sat in the same chair, Nadler–a head shorter than Schiff–would look small.

Pelosi sent word down: there would have to be a change of furniture. And when Judiciary convened on Dec. 4, Nadler was seated in a leather-backed chair that reached no higher than his ears.

Impeachment was the culmination of Pelosi’s broader effort to hold Trump in check. For the past year, she has overseen investigations by six different congressional committees digging into everything from Trump’s tax returns and allegations of Administration corruption to foreign emoluments and the Russian entanglements Mueller helped uncover. Congressional committees tend to be territorial, but Pelosi convened the six committees’ chairmen weekly, and sometimes more often, to ensure they didn’t duplicate efforts or step on one another’s toes.

She has also guided a far-reaching effort to rein in Trump through the courts. She hired a 40-year Justice Department veteran, Douglas Letter, to head the House general counsel’s office, a secretive team of nine lawyers, and confers with him on every legal filing, every subpoena. Together they have chosen cases designed to set precedents that affirm Congress’ powers and shore up the institution. “She’s calling the shots,” Letter tells TIME, in a rare interview. Starting with his job interview, Letter says, Pelosi correctly predicted that “we would get stonewalled” by Trump and his lawyers, and would have to litigate in the courts more than usual. “She insisted we would try to pick, particularly for subpoena enforcement, really good cases.”

Courts tend to view litigation between the Legislative and Executive branches with unease. Judges are leery of refereeing what they view as essentially political disputes. But Pelosi and Letter’s approach has produced a string of victories. Courts have ruled in favor of releasing Trump’s tax returns and other financial records, compelled the release of grand-jury materials from the Mueller investigation and dismissed the Administration’s arguments for blocking witnesses. In a blistering November opinion, U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson ruled that Donald McGahn, Trump’s former White House counsel, must testify, and that the Administration’s argument to the contrary “simply has no basis in the law.” She added, “The primary takeaway from the past 250 years of recorded American history is that Presidents are not kings.”

As those court cases got tied up in appeals, though, progress in the courts did little to satisfy those eager to use the ultimate tool of presidential accountability. Pelosi resisted impeachment throughout the summer, even as more and more members of her caucus endorsed it. “Many of them were out there for impeachment like a year ago, right after we won,” she says, but she insisted on moving deliberately in order to make the strongest possible case. “I said we’ll go down this path when we’re ready,” Pelosi says. She told her colleagues that they had to wait for the investigation and litigation to play out.

The frustration built outside of Congress too. In her San Francisco district in August, Pelosi appeared at a banquet in her honor–the “Heart of the Resistance” dinner. She had barely begun to speak when a group of young activists rose in the back, standing on chairs and unfurling black fabric banners with white lettering. TIME TO IMPEACH, they said. WE CAN’T WAIT. A young woman shouted, “People are being killed by white supremacists!” A man said, “We are your constituents!” As the crowd chanted, “Let her speak,” a burly labor organizer got in the activists’ faces, and for a moment it seemed as if they might come to blows before hotel security escorted the protesters out.

“It’s O.K.,” Pelosi said from her position at the front of the room. “I’m going to speak. I’m the Speaker of the House!” When she did speak, however, the word impeachment did not escape her lips.

A few weeks later, the Ukraine scandal changed the short-term politics and the long-term stakes. In mid-September, media outlets started to report that Trump had tried to bully his Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky, into publicly announcing an investigation of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, using White House access and congressionally approved foreign aid as leverage. His actions had alarmed government officials, leading an intelligence-community whistle-blower to file a secret complaint.

Trump had applied the pressure during a phone call in July, the day after Mueller testified before Congress. To House Democrats, it seemed Trump was setting a dangerous precedent of presidential impunity, soliciting foreign assistance in the 2020 election just as he’d been accused of doing in 2016. “I was one of those who were very reluctant to proceed” with impeachment, says Representative Ed Perlmutter, a Democrat from Colorado who is close to Pelosi despite trying to block her from the speakership after the 2018 midterms. “But putting people’s lives at risk by holding up that aid money, extorting the Ukrainian President to do the political bidding of the President–that was something that changed the calculation for everybody.”

Pelosi had already begun preparations toward impeachment when, at 5 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 23, she took a call from a group of seven freshman Democrats. All of them had military and intelligence backgrounds; all had flipped Republican districts; all had opposed impeachment to this point. Now they told her they were jointly writing an op-ed, to appear that evening on the Washington Post’s website, endorsing an impeachment inquiry. “We have devoted our lives to the service and security of our country,” the op-ed read. “These allegations are stunning, both in the national security threat they pose and the potential corruption they represent.”

Flying back to Washington from New York City that night, Pelosi began drafting an announcement in her looping cursive hand on a piece of loose-leaf paper. The next morning, the Speaker was in her airy Georgetown penthouse condo when she received an unscheduled call from the President. It was 8:16 a.m. Trump was in New York, preparing for a speech to the U.N. The subject of the call was ostensibly gun control, a topic dear to Pelosi’s heart. But that turned out to be a pretext.

Trump quickly turned to the subject of the July 25 Zelensky conversation. There was “no pressure at all,” he insisted, according to a source familiar with the conversation between Pelosi and the President. The call was “100% perfect. I didn’t ask him for anything.” Trump added, “Literally, you would be impressed by my lack of pressure.”

Pelosi was unconvinced. “Mr. President,” she said, “we have a problem here.” She repeatedly urged the President to release the still hidden whistle-blower complaint that had set off the controversy. And she reminded him that as the longest-serving member of the House Intelligence Committee, this allegation was “in my wheelhouse.” As the conversation grew tense, she urged him one more time to release the complaint. “I have to go give a speech,” Trump said, and hung up.

To Pelosi, Trump’s belief that the Zelensky call was “perfect” showed an inability to distinguish right from wrong. For months, she had believed voters in the 2020 election should be the ones to remove Trump from office. Now she was increasingly convinced it would be dangerous to allow him to continue his term without rebuke.

At 4 p.m. that afternoon, she met with her caucus and outlined her plan to announce an impeachment inquiry. There were no objections. As her 5 p.m. announcement drew near, an aide tugged at her sleeve, urging her to go upstairs and run through the speech just once before she went out and delivered it. Finally she turned on him, snapping, “I walk into rooms and read teleprompters all the time. That’s what we’ll do.”

Then it was time to face the cameras for history. “The actions taken to date by the President have seriously violated the Constitution,” Pelosi said. “The President must be held accountable. No one is above the law.”

Now that the House has impeached Trump in a nearly party-line vote, it’s fair to ask how much Pelosi’s careful management of the process achieved. The Senate Republican leader, Mitch McConnell, has declared he will work to ensure Trump is acquitted. McConnell’s Democratic counterpart, Chuck Schumer, seems to agree that Trump’s acquittal is a foregone conclusion. “I don’t want to second-guess” the outcome, Schumer tells TIME. “But these Republicans are not the Republicans of old. They are totally supine in their obeisance to Trump.” Yet Schumer agrees with Pelosi that “we have no choice, given the President’s lack of respect for democracy and the Constitution.”

Republicans gloat that impeachment has strengthened Trump politically–that somehow, a process designed by the founders to constrain a President has perversely achieved the opposite. Trump’s re-election campaign has harnessed his supporters’ outrage over impeachment to raise buckets of money. As the drama played out over the final three months of 2019, Trump raked in $46 million, his best quarterly haul of the year and more than any of his Democratic rivals have raised over a similar period. Within 72 hours of Pelosi’s Sept. 24 announcement that Democrats would move forward with an impeachment inquiry, the Trump campaign pulled in $15 million in small-dollar donations.

Critics accuse Pelosi of caving to pressure and violating her own conditions to pursue Trump’s impeachment. Even Republicans who aren’t big Trump fans have “been sort of driven toward him by this–they do feel that Democrats overplayed their hand,” says Representative Peter King, a New York Republican. “This whole thing has been a rush to judgment.”

But Pelosi’s allies say holding out until the Ukraine scandal broke strengthened her hand. “It’s made her an even more powerful voice in this moment,” says Representative David Cicilline, Democrat of Rhode Island. “She resisted this for so long because she really understood the consequences to the country. That gives her tremendous credibility with the American people when she came to the conclusion it was necessary.”

It’s an open question whether Pelosi’s gamble has the public’s support. In polls, a slight plurality of Americans–just over 49%–support Trump’s impeachment, according to averages tabulated by FiveThirtyEight. That number shot up after the scandal began, and is historically high, but it has barely budged since October, and Trump’s approval rating has remained steady in the low 40s as well. Democratic pollster Geoff Garin says that despite GOP claims to the contrary, “there’s no evidence that impeachment has changed the fundamental dynamics of the 2020 election.” Trump’s opponents, he contends, are even more galvanized by impeachment than his supporters are. And by November 2020, Garin says, the data suggest that voters will base their decisions far more on issues like health care than on impeachment.

In mid-December, I sat down with Pelosi again and asked her to respond to some of the criticism of the process. The Speaker was battling a lingering winter cold, and was in the midst of last-minute negotiations with the White House and Senate on a $1.4 trillion spending deal to avert a shutdown while sharply cutting back Trump’s requested border funding.

The idea of a rush to impeachment exasperates the Speaker, who points out that the White House limited the evidence available with its unprecedented stonewalling. And Pelosi contends that the process is merely an extension of the prior investigations of Trump. “This has been going on for 2½ years, since the Justice Department tasked Director Mueller to go into the investigation,” she says. “It’s been going on for a long time. The aha moment was Ukraine. But the pattern of behavior was very self-evident over time.”

Many Democrats hoped some Republicans might support impeachment; Pelosi claims nothing ever surprises her. “It’s disappointing to see that they are ignoring their own oath of office,” she says. “The President must be held accountable. And the fact that the Republicans are even in denial of the factual basis of what happened is sad for our country.”

On Dec. 17, the night before the full House would debate and vote on Trump’s impeachment, Pelosi met behind closed doors with top caucus members on the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee. She hinted, for the first time, that she was contemplating a curveball: declining to immediately transmit the impeachment articles to the Senate after the House passed them. “The rule empowers the Speaker to be able to decide how to send the articles and when to send the articles over to the Senate,” she said, according to an aide who was in the room. “My view is we don’t know enough about what they are going to do. We want to see what [is] their level of fairness and openness and the rest.”

Pelosi, according to an aide, had been mulling the tactic since she heard former Nixon White House counsel John Dean float the idea on CNN on Dec. 5. In the committee meeting, she added that she believed McConnell would be motivated to move. “Somebody said to me today that he may not even take up what we send. [But] then [Trump] will never be vindicated,” she said, according to the aide in the room. “He will be impeached forever. Forever. No matter what the Senate does.”

The following day, Pelosi presided over the floor vote on impeachment, wearing a striking black suit to project solemnity, accessorized with a large gold brooch of the Mace of the Republic, a symbol of the House. When scattered cheers broke out inside the chamber after the first article was approved, she sternly and silently shushed them with a glare and a sharp gesture. After the vote, she announced that she did not plan to transmit the articles right away, saying she could not determine how to appoint House impeachment managers until the Senate decides on its rules for the trial.

McConnell has mocked the idea that Pelosi or Schumer can shape the Senate trial to their liking. But he’s also said he won’t start it until Pelosi sends the articles, and it’s clear from Trump’s tweets and statements that the unresolved situation bothers him. Moreover, the delay is allowing facts to emerge. Over the two-week holiday break, newly unredacted emails showed Pentagon officials worrying about the legality of Trump’s effort to withhold military aid from Ukraine. And on Jan. 6, former National Security Adviser John Bolton, potentially a key witness to Trump’s alleged actions toward Ukraine, announced he would testify before the Senate if subpoenaed. On Jan. 7, McConnell announced that he had enough Republican votes to begin the trial, and Democrats in both chambers appeared to be getting restless–but still Pelosi refused to budge.

The gambit is reminiscent of another Pelosi maneuver designed to exploit Trump’s insecurities. Pelosi retook the speakership a year ago amid a government shutdown triggered by Trump’s demand for border-wall funding. She refused to negotiate on the matter until the government reopened. As the stalemate dragged on, Pelosi seized on an unexpected source of leverage: she postponed Trump’s State of the Union address to Congress, knowing that he prized it as a televised set piece showcasing his power.

Then she stubbornly waited out her adversary. “The President tried to break us in January [2019] by throwing us into a government shutdown at the same time we were transitioning into the majority,” says Hakeem Jeffries, a Democratic Congressman from New York who serves as caucus chairman. “We held together, and instead of breaking us, we broke him. It ended in unconditional surrender.”

This power struggle between the branches of government was not Pelosi’s vision. She preferred the emphasis to be on the Democrats’ policy agenda. She believed that kitchen-table concerns were more important to voters and wanted to show that Democrats are capable of governing. Despite Trump’s criticism of the “do-nothing Democrats,” the House has passed nearly 400 bills, most with GOP support. If there’s a single morning that captures how Pelosi has juggled the priorities of policymaking and oversight, it is Dec. 10, when she led the 9 a.m. announcement of the impeachment articles, then proceeded directly to a 10 a.m. press conference to announce that the House had made a deal to pass the President’s revision of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Her approach is a stark departure from how the GOP handled Barack Obama’s presidency–opposing Obama at every turn, determined not to give him victories even on uncontroversial matters. Pelosi and Schumer have found ways to work with Trump, particularly on trade, prescription drugs and infrastructure, an approach that rankles the left. “Democrats should not be giving Donald Trump wins that normalize his presidency and give him a set of accomplishments to campaign on,” says Brian Fallon of the liberal group Demand Justice. “He benefits vastly more from a bipartisan trade deal than they do.” In a stroke of irony, the Speaker whose moderate colleagues tried to get rid of her for fear she struck heartland voters as too far left is now hailed–or derided–as a moderating force.

Yet House Democrats from all wings of the diverse caucus say they are more unified than at any time in recent memory. “I think we’re doing the very best we could,” says Representative Chrissy Houlahan of Pennsylvania, one of the authors of the national-security freshmen’s op-ed. Liberal Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, agreed: “It’s been a very disciplined approach.”

That comity will be tested as Washington heads into an election year. More is at stake than the balance between the parties. The institutions of American democracy are being tested. The checks and balances designed by the founders depend on the coequal branches’ ability to stand up to one another. “She’s had a herculean task, and she’s done it brilliantly,” says Jonathan Rose, a former Nixon and Reagan Administration lawyer affiliated with the anti-Trump conservative legal group Checks and Balances. “I never thought I’d be for Nancy Pelosi in my lifetime.”

Pelosi, for her part, won’t admit to any preference for her party’s 2020 nominee. But the Speaker, as usual, has a strategy for how she believes the Democrats should proceed. “The message has to be one that is not menacing,” she says. “What works in Michigan works in San Francisco, about job creation and the rest. But what works in San Francisco may not work in Michigan. Michigan is where we must win, and we must win in the Electoral College. We won the House last year by having mobilization at the grassroots level. We have to do that again.” The question for Democrats now may have less to do with the effects of Pelosi’s actions than whether they heed her advice.

With reporting by Alana Abramson and Brian Bennett/Washington