This project was supported by the Pulitzer Center

The wheels are still attached to the house trailer that Pamela Rush calls home, but the 49-year-old mother of two is trapped. A lifelong resident of Lowndes County, Alabama, she lives off disability checks, struggling to pay the bills on a ninth-grade education. It’s hard to attribute her situation to any one cause—she was born in one of the poorest counties in one of the poorest states and, like the rest of the county’s mostly African-American population, she wrestles with the legacy of slavery and systemized discrimination. Just down the road from her home are the sharecroppers’ quarters where she was born.

Yet the most immediate source of Rush’s troubles is immediate: the puddle of sewage that has collected in her backyard, brewing with human feces. Whenever the toilet inside is flushed, the waste travels through a 10-ft. pipe straight to her backyard. Thousands of the county’s residents are in the same situation. Local government won’t pay to build infrastructure to connect them to proper wastewater-disposal lines, so they’re left to deal with the myriad problems caused by living in sewage that bubbles up into showers and bathtubs. A 2017 study of county residents found that 34% of participants suffer from hookworm, a parasitic infection contracted by walking barefoot on soil contaminated by fecal matter; among the issues associated with the disease is slow development in children. Charlie Mae Holcombe, 71, who lives in the area, said that the lack of sanitation accounts for the allergies, asthma and heart problems pervasive in the county. “Everyone’s dying,” she tells photographer Matt Black. Hers is one of dozens of stories Black gathered as he documented America’s water crisis for over a year.

For most Americans, water does not get a second thought. It flows at the turn of a knob, at a cost that is all but negligible. This is as it should be. Being essential to life, clean water is a right under international law and U.N. declarations. Yet in the U.S., it’s far from guaranteed. More than 30 million Americans lived in areas where water systems violated safety rules at the beginning of last year, according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency. Others simply cannot afford to keep water flowing. As with basically all environmental and climate issues, poor people and minority communities are hit hardest.

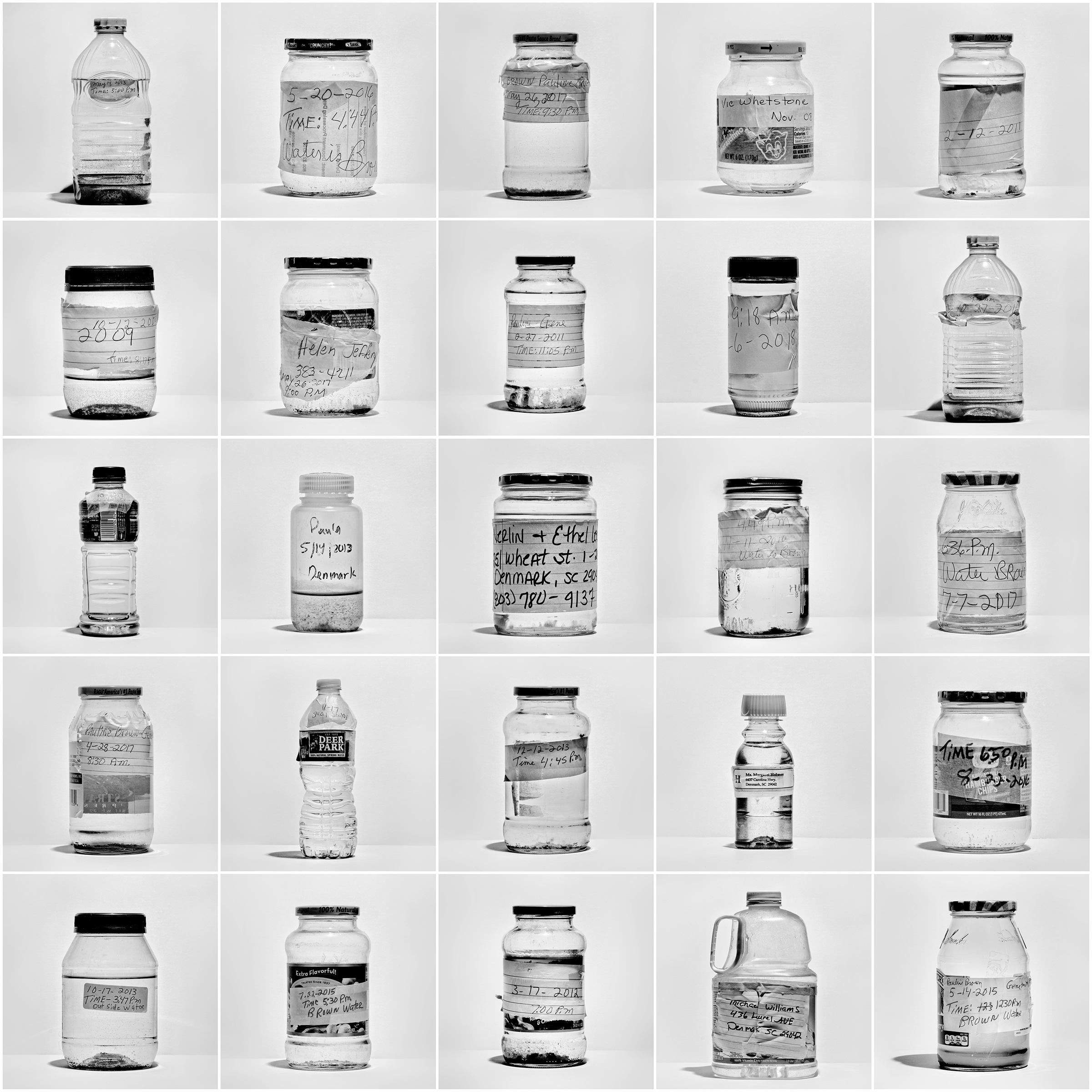

In Denmark, S.C., local officials added the untested chemical HaloSan to drinking water, intending to combat rust-like deposits but leaving residents to deal with a slew of unexplained skin ailments. Suspicious of the water, Eugene “Horseman” Smith and his wife Pauline Ray Brown have collected samples for a decade, sharing them with scientists and an attorney. “Denmark is like a third-world country,” says Smith.

In Inez, Ky., residents still battle the remnants of millions of gallons of toxic sludge, replete with arsenic and mercury, that leaked into the water two decades ago. Locals face liver and kidney damage, as well as increased risk of cancer.

It’s a public-health problem, the root of which varies from place to place—old pipes silently poisoning entire cities with lead, industrial sites leaking the carcinogenic industrial chemical known as PFAS into the waterways, uranium seeping into groundwater from where it’s been mined. But the downstream effects are strikingly similar: damage to health that exacerbates the trials of poverty and a frayed social safety net. These in turn become years wiped off life expectancy and points lost from IQ scores.

In the Navajo Nation, where more than 300,000 people reside in a territory that stretches across parts of Utah, New Mexico and Arizona, residents unknowingly drank and played in water that uranium mining had made extremely hazardous. “Growing up, they didn’t talk about how dangerous it was,” said Melissa Sloan of Tuba City, Ariz., before she died in December of kidney cancer. “I drank the water; I bathed in the water.”

A striking number of people, including babies, show traces of uranium in their blood. Infections develop in those who dare to shower. Summer Wojcik, a triage nurse at Utah Navajo Health System, says health care providers ask patients with infections if they have access to clean water. If not, they may keep them in a health care facility for a few days, to improve the odds of healing. “You’ll hear those types of stories all over—infections, cancers,” she says. “We have got to get fresh water for these people.”

Beyond the diseases, contaminated water helps account for social decay. Residents on a desperate quest for safe water routinely drive for hours to buy and stash it. Jeremiah Kerley, 61, says he hitchhikes to Flagstaff to sell his plasma. “It’s a source of income,” he says. “I use that to pay for our water.”

For those without it, water amounts to an ongoing crisis. But no great urgency is felt in Washington, D.C., or in state capitals. Laws may be out of date, and existing rules ignored, but as an “issue,” water seems to sprout up only when a seemingly one-off event like the Flint water crisis captures public attention.

But Flint is not a one-off event. In Michigan, officials put an entire community at risk to save money, then lost a bet that the risks would go unnoticed. Similar wagers are placed by politicians and policymakers across the country. “Legal standards are often compromises between what the data shows in terms of toxicity and risk, and how much it’s going to cost,” says Alexis Temkin, a toxicologist at the Environmental Working Group, a research and advocacy organization.

The odds are getting worse. A 2017 report card from the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation’s drinking-water infrastructure a rating of D, and assessed that the U.S. needs to invest $1 trillion in the next 25 years for upgrades. The alternative is more erosion, not by water but by the damage that occurs in its absence.

In Inez, Ky., where the local riverway has been contaminated since 2000 by a giant runoff of coal-mining by-products, water bills have skyrocketed, and yet the residents say the problem hasn’t been fixed. The tap produces what one resident called “fishy water.” But local police made news when they arrested a resident for refusing to pay for water. “They’ve destroyed the waterways to mine coal,” says Nina McCoy, an Inez resident. “We’re all fighting our little fires, and we’re not realizing that the fire is coming from above, and it’s raining down on us.” —With reporting by Kara Milstein

This article is part of a special project about equality in America today. Read more about The March, TIME’s virtual reality re-creation of the 1963 March on Washington and sign up for TIME’s history newsletter for updates.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision